SEARCH RESULTS FOR: 2023

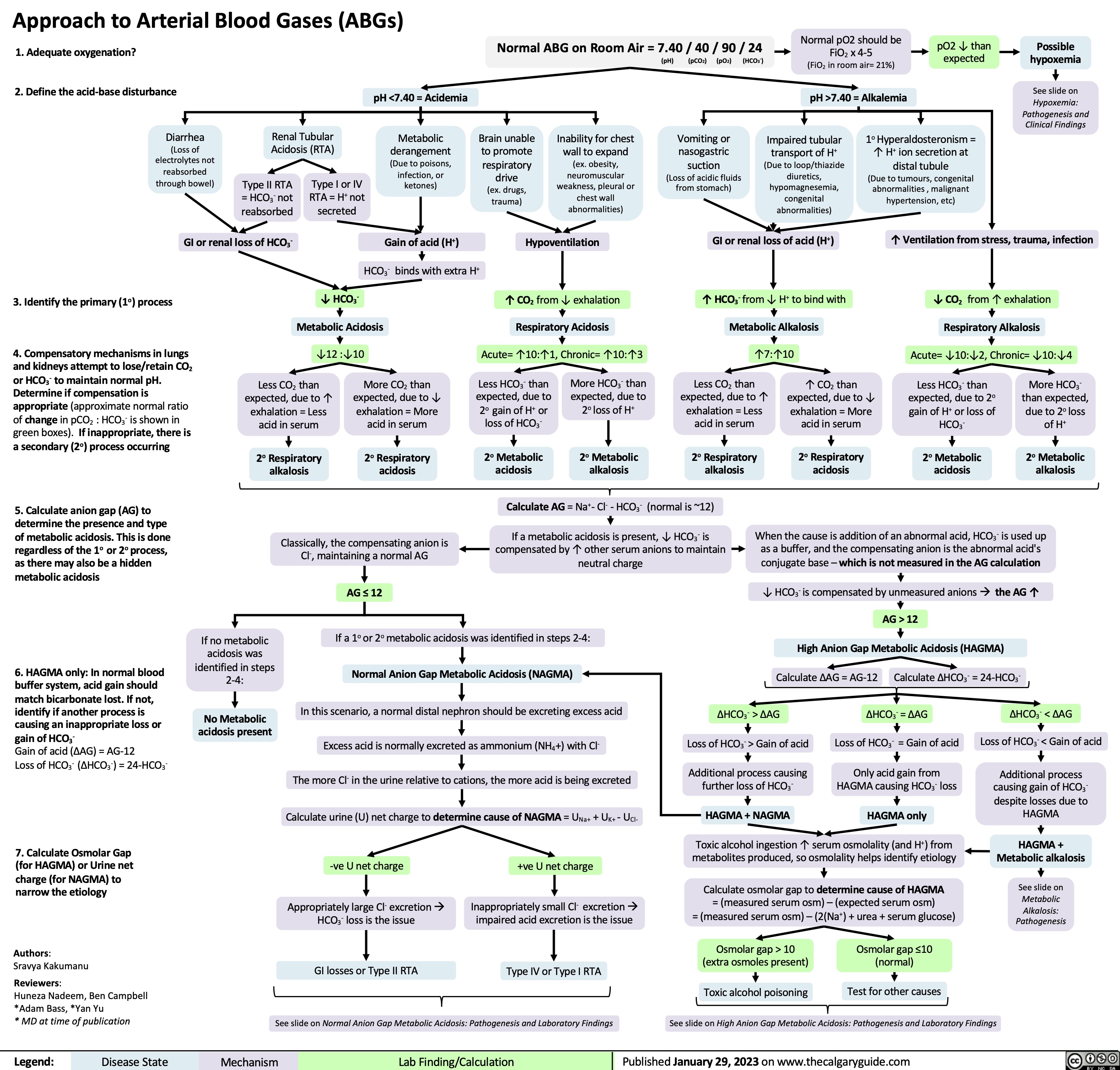

Approach to Arterial Blood Gases ABGs

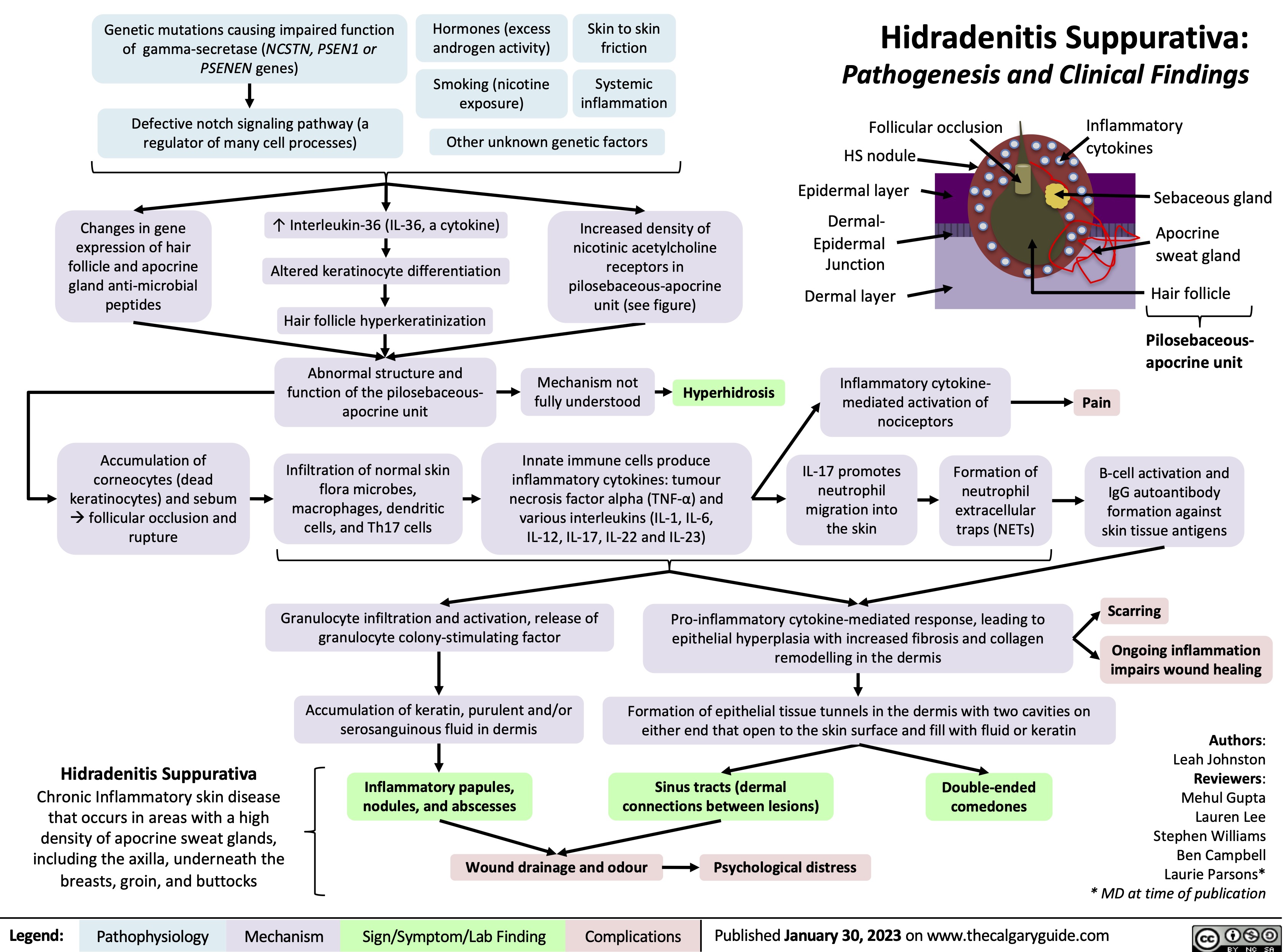

Hidradenitis Suppurativa

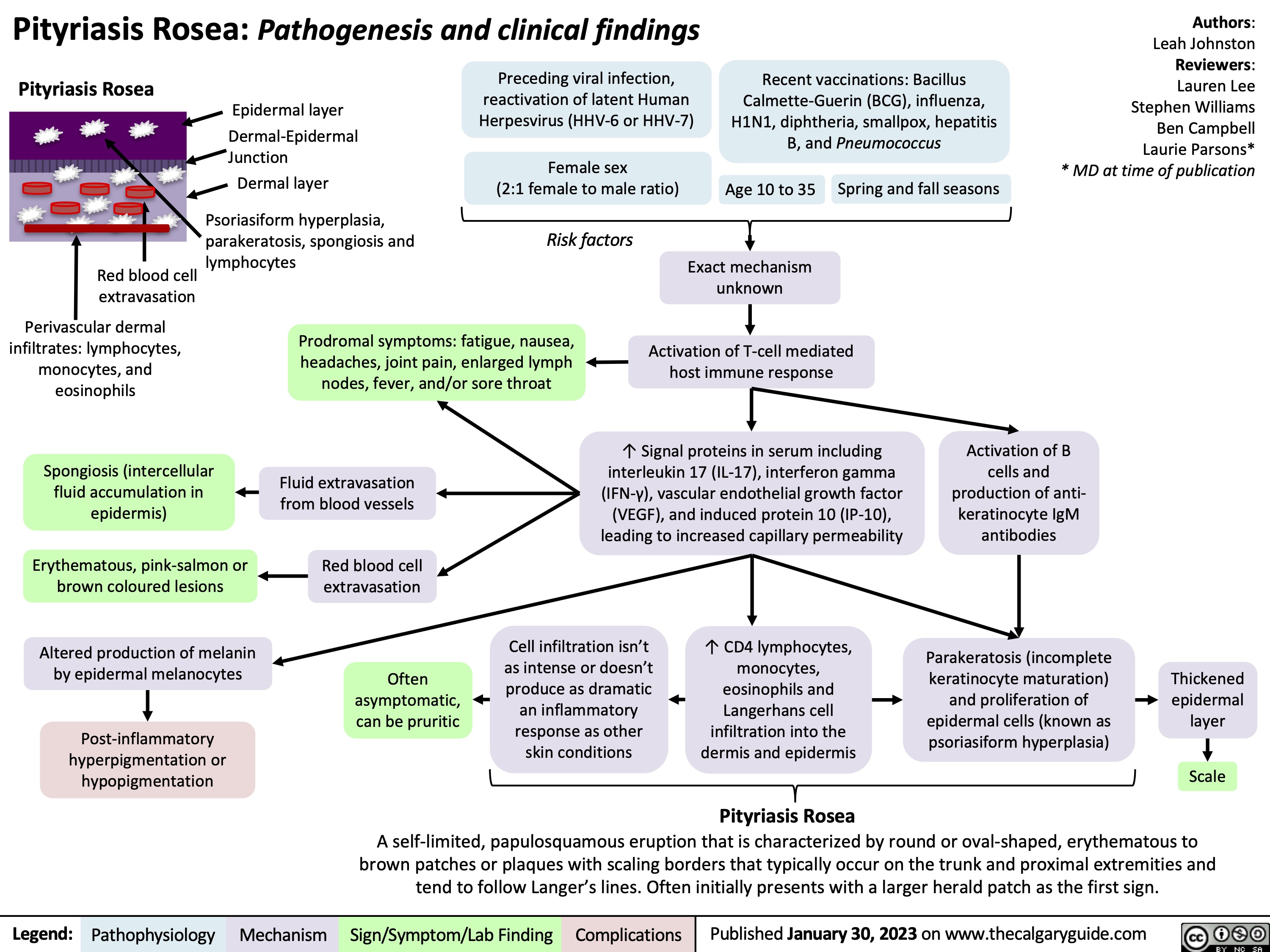

Pityriasis Rosea

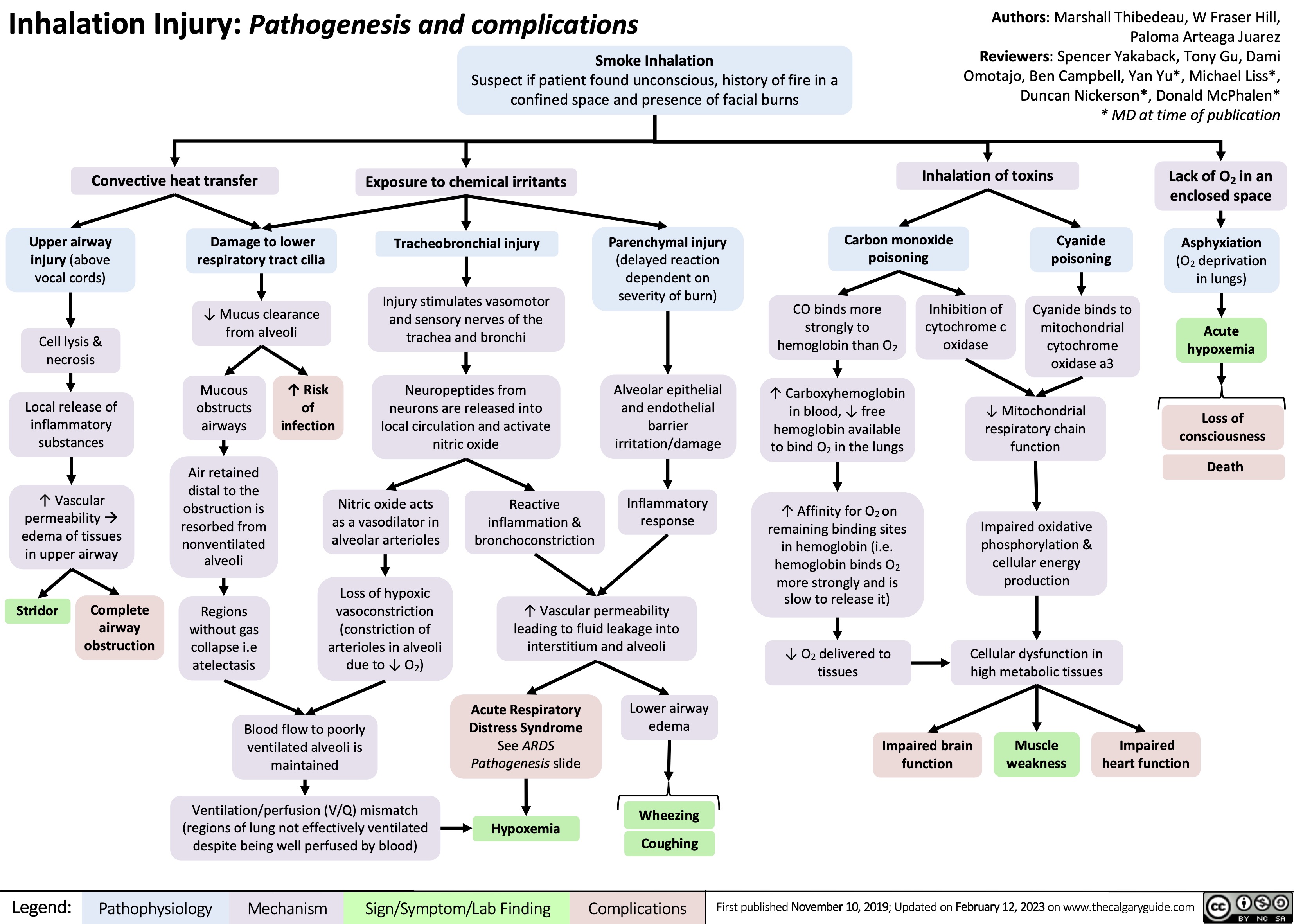

Inhalational Injury

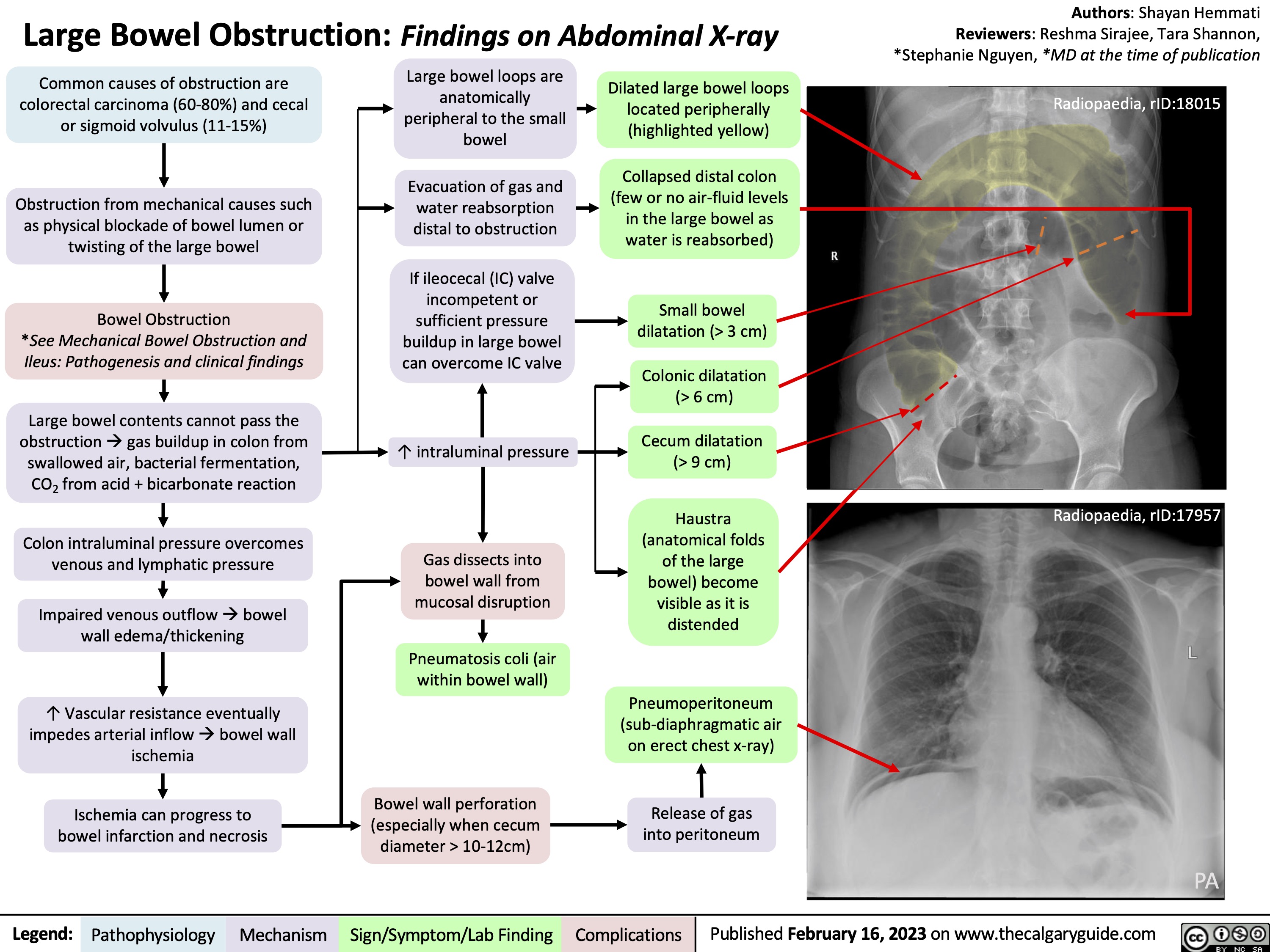

Large Bowel Obstruction: Findings on Abdominal X-ray

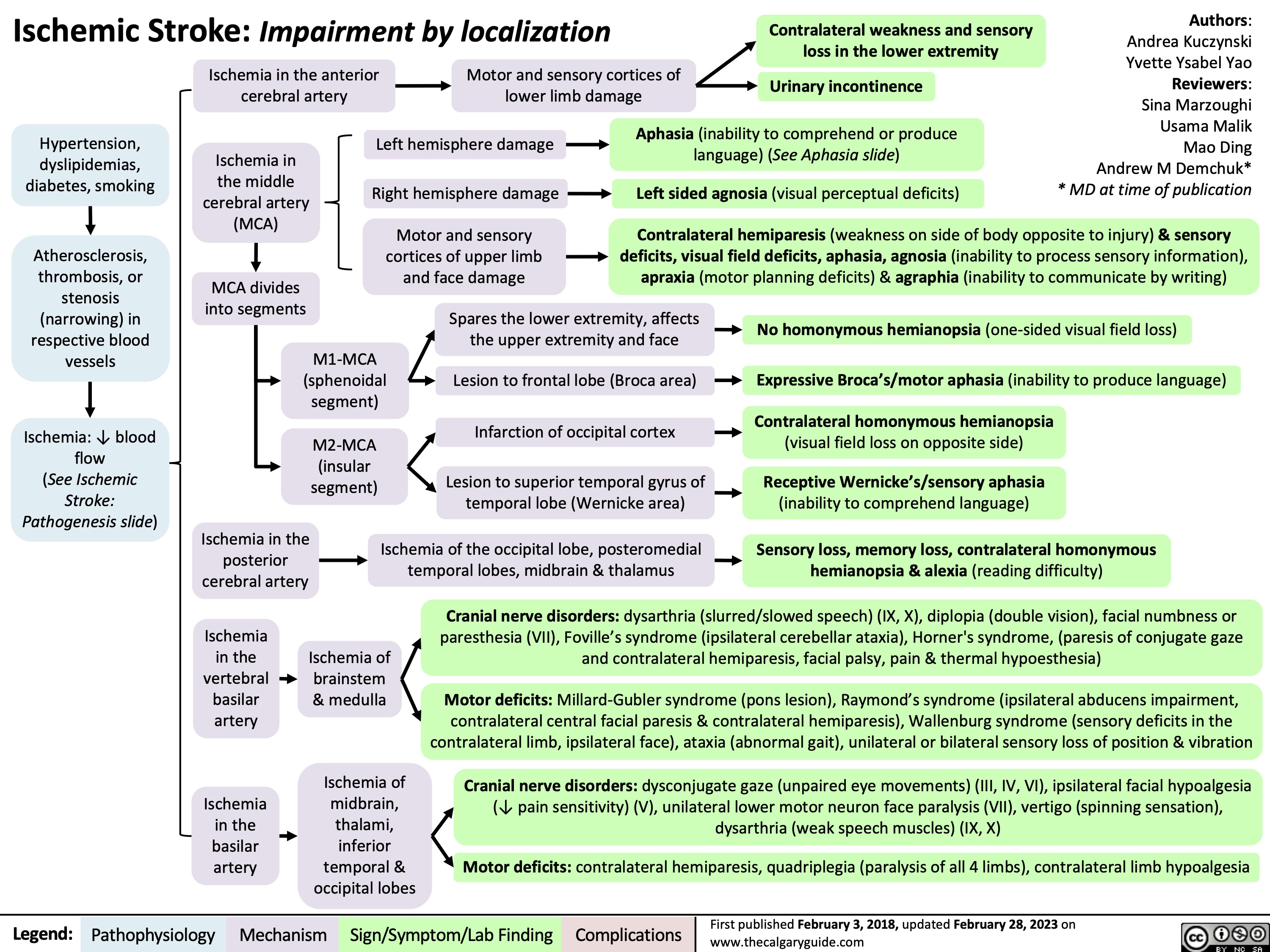

Ischemic Stroke Impairment by Localization

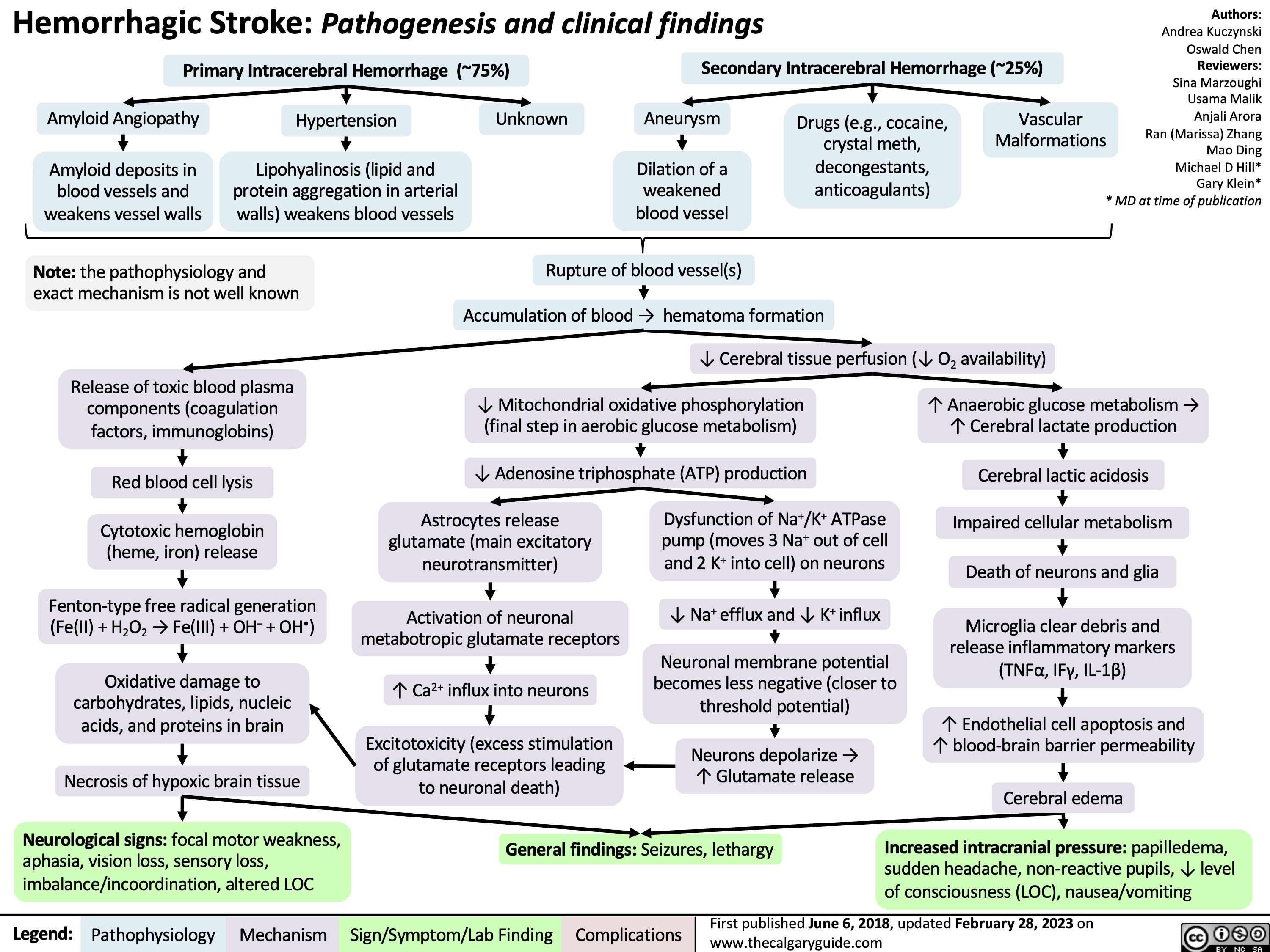

Hemorrhagic Stroke

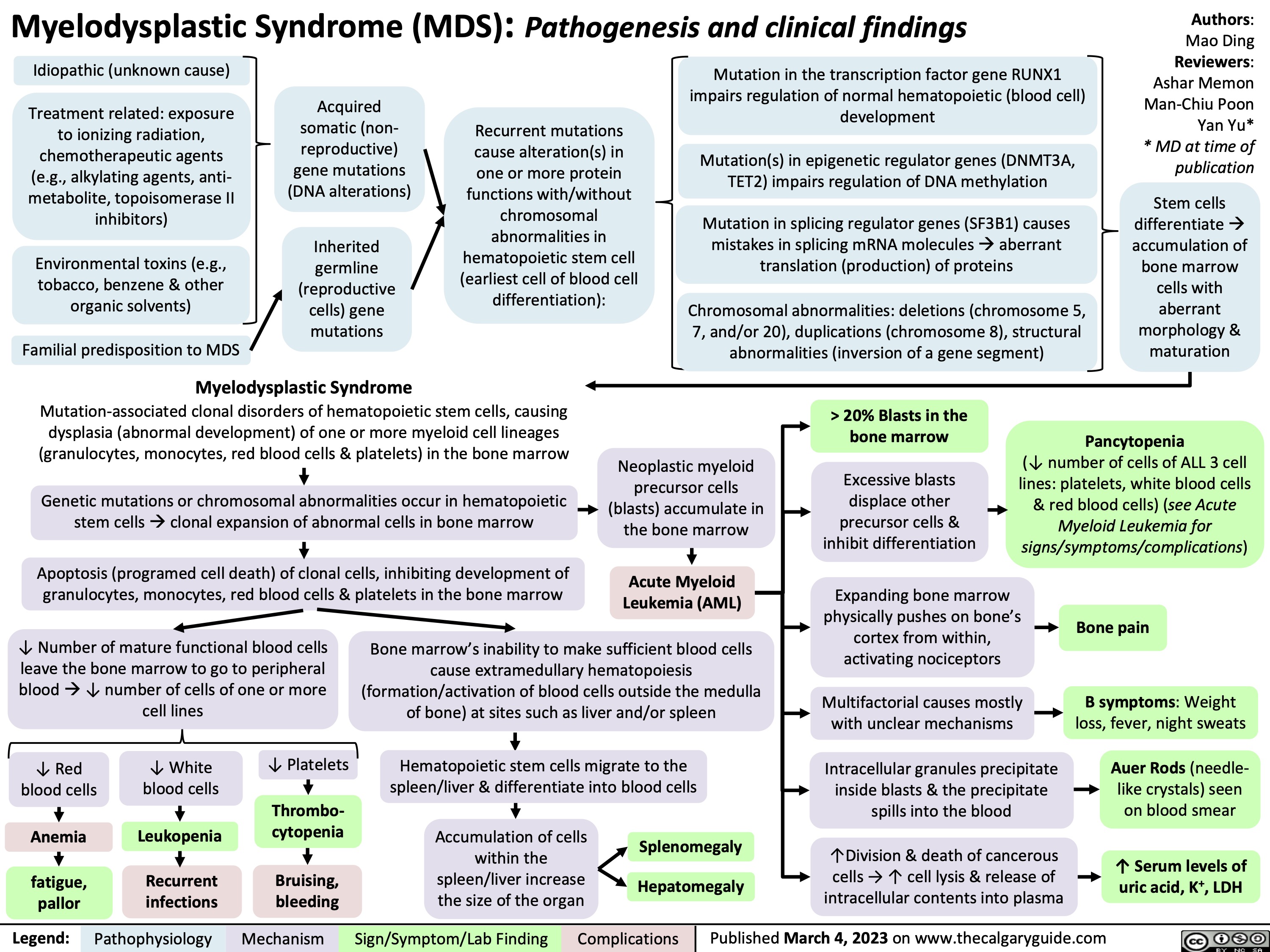

Myelodysplastic Syndrome Pathogenesis and clinical findings

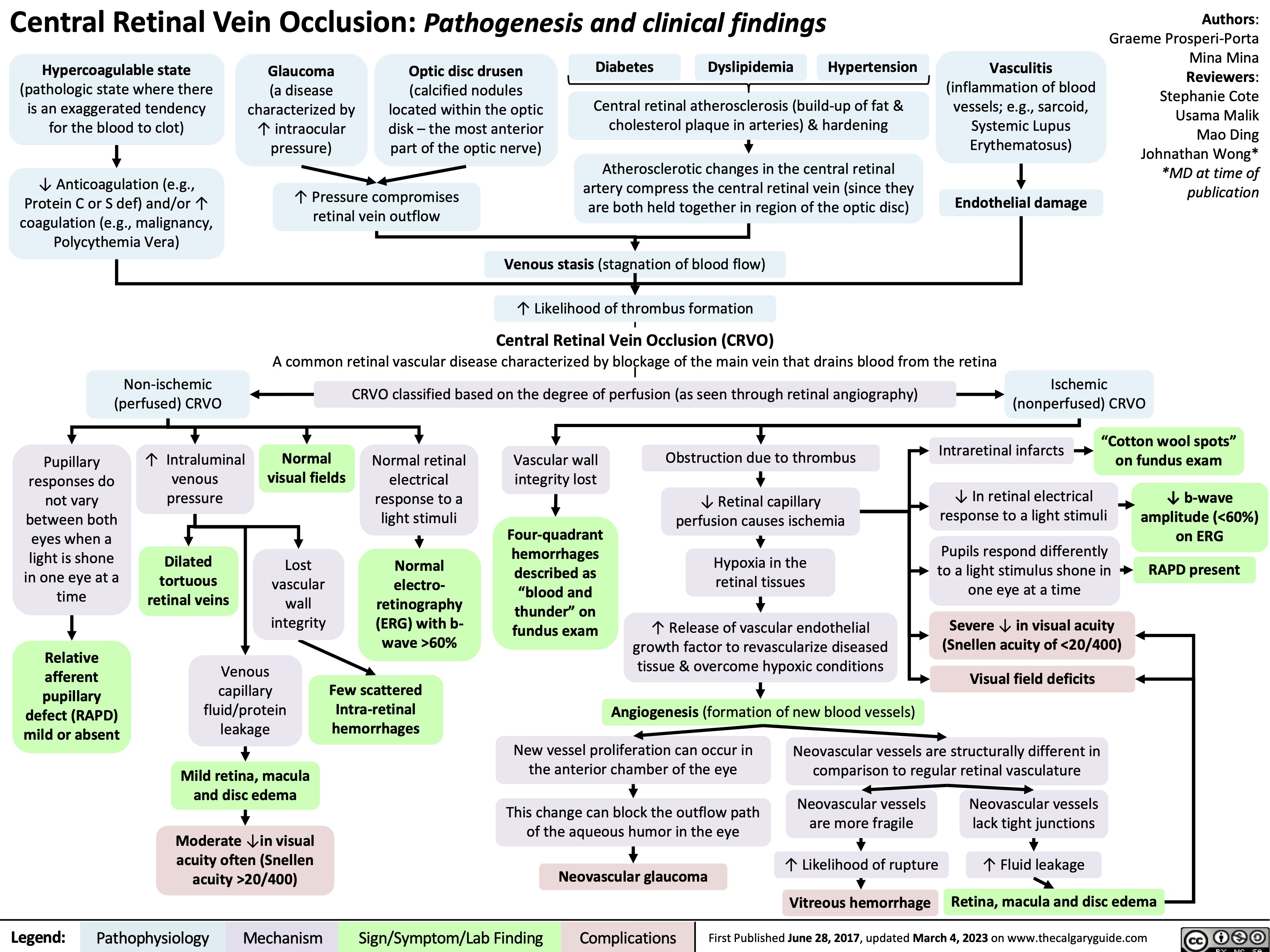

Central Retinal Vein Occlusion

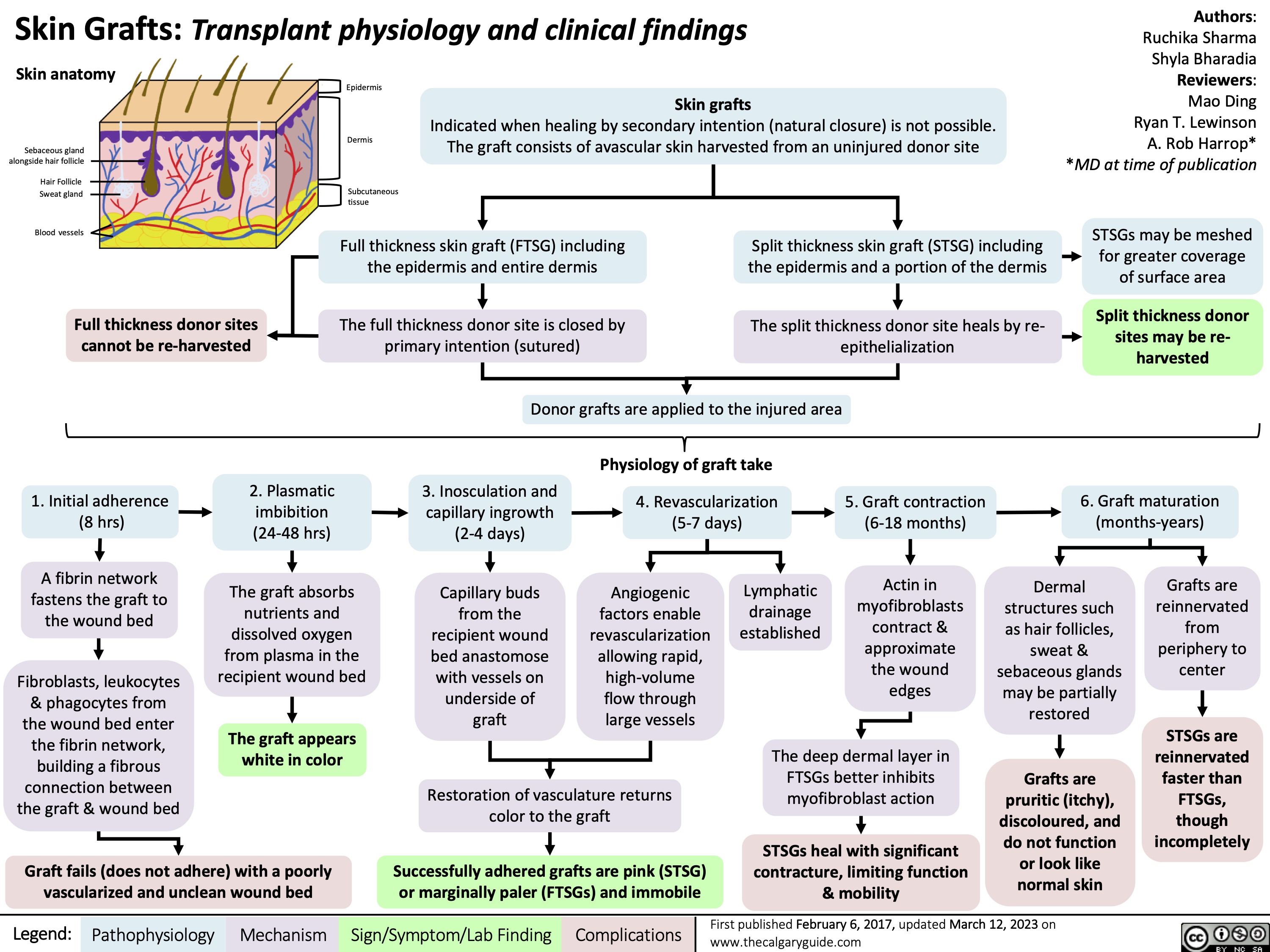

Skin Grafts Transplant physiology and clinical findings

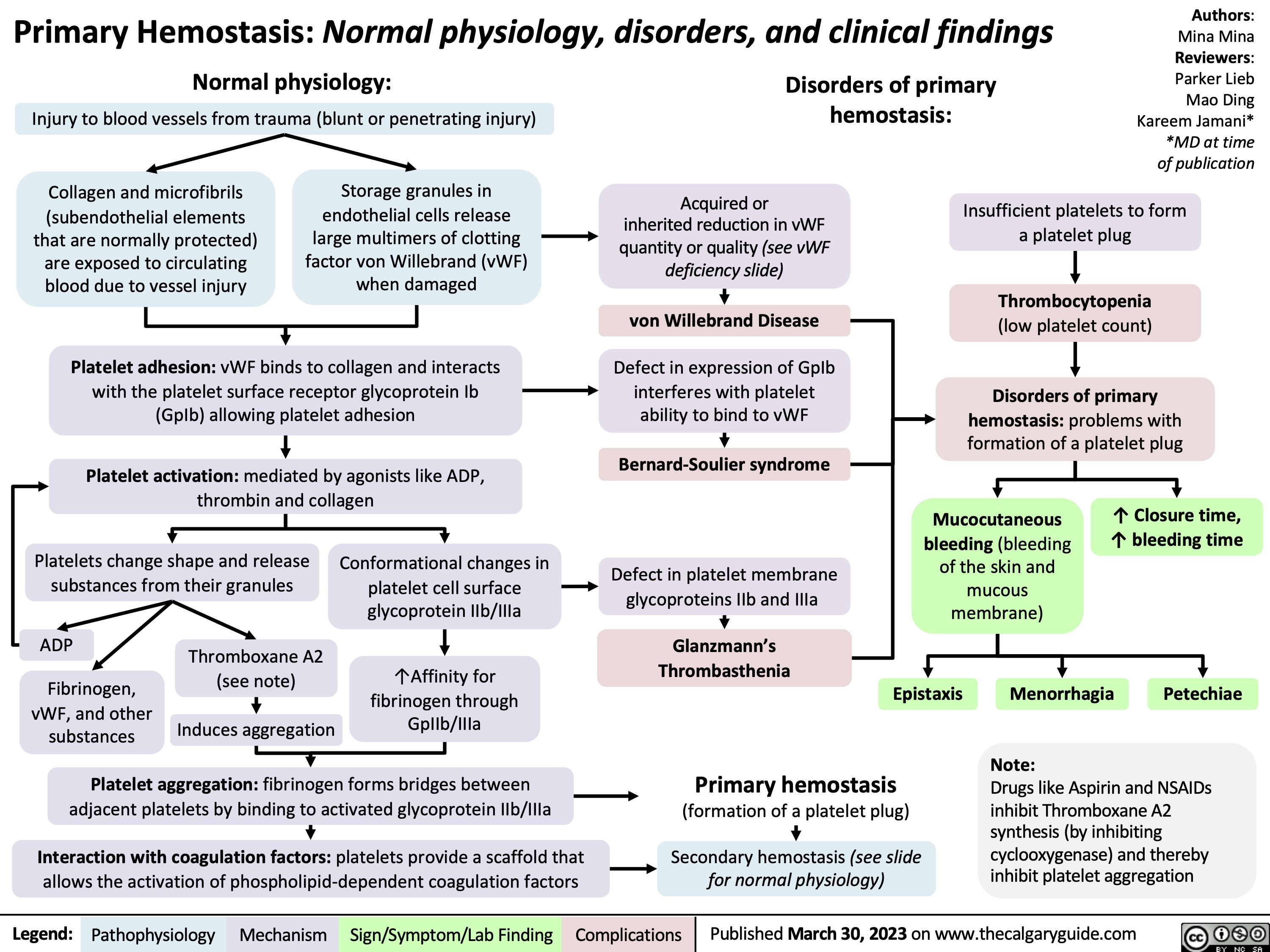

Primary Hemostasis

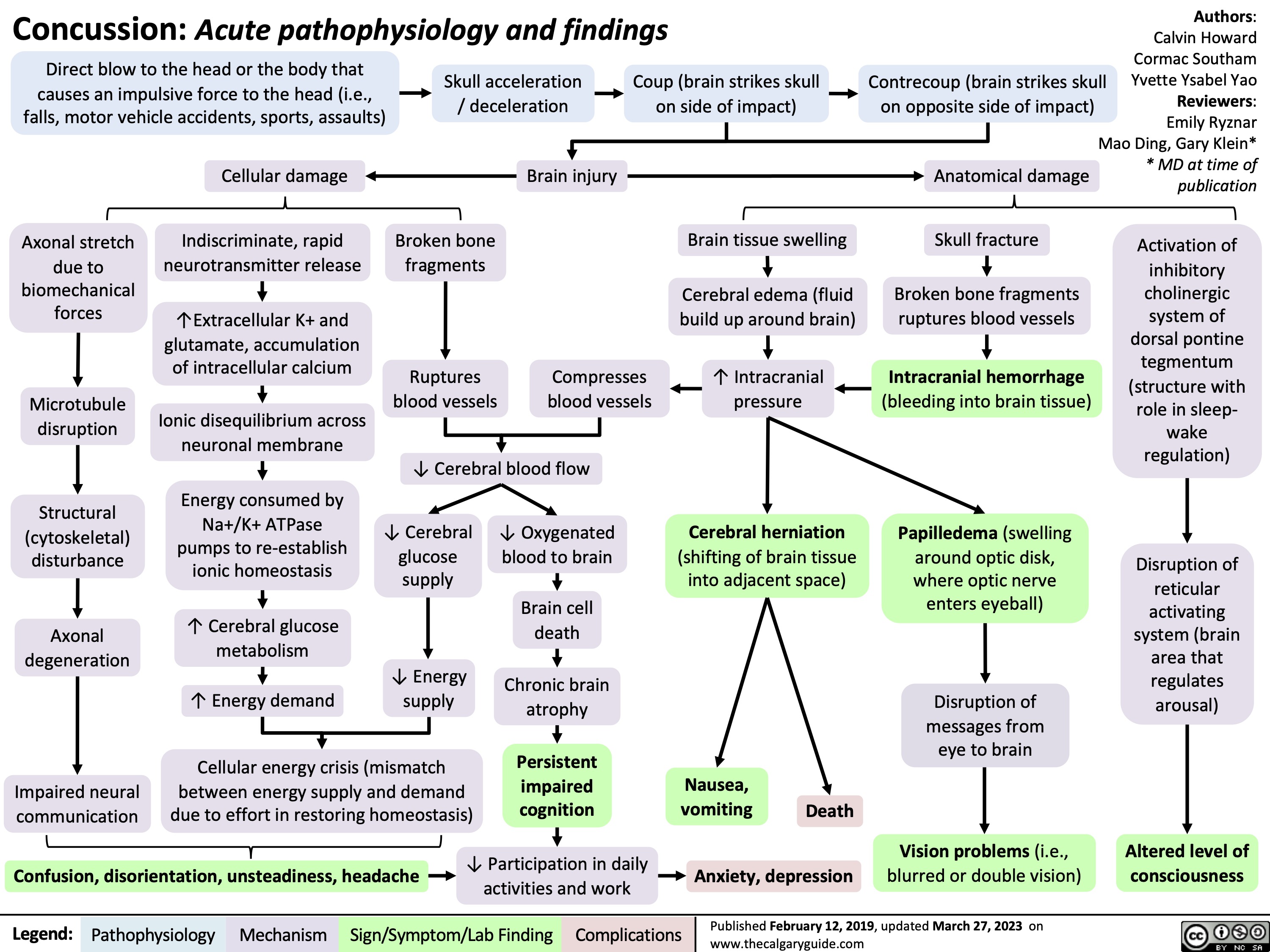

Concussion

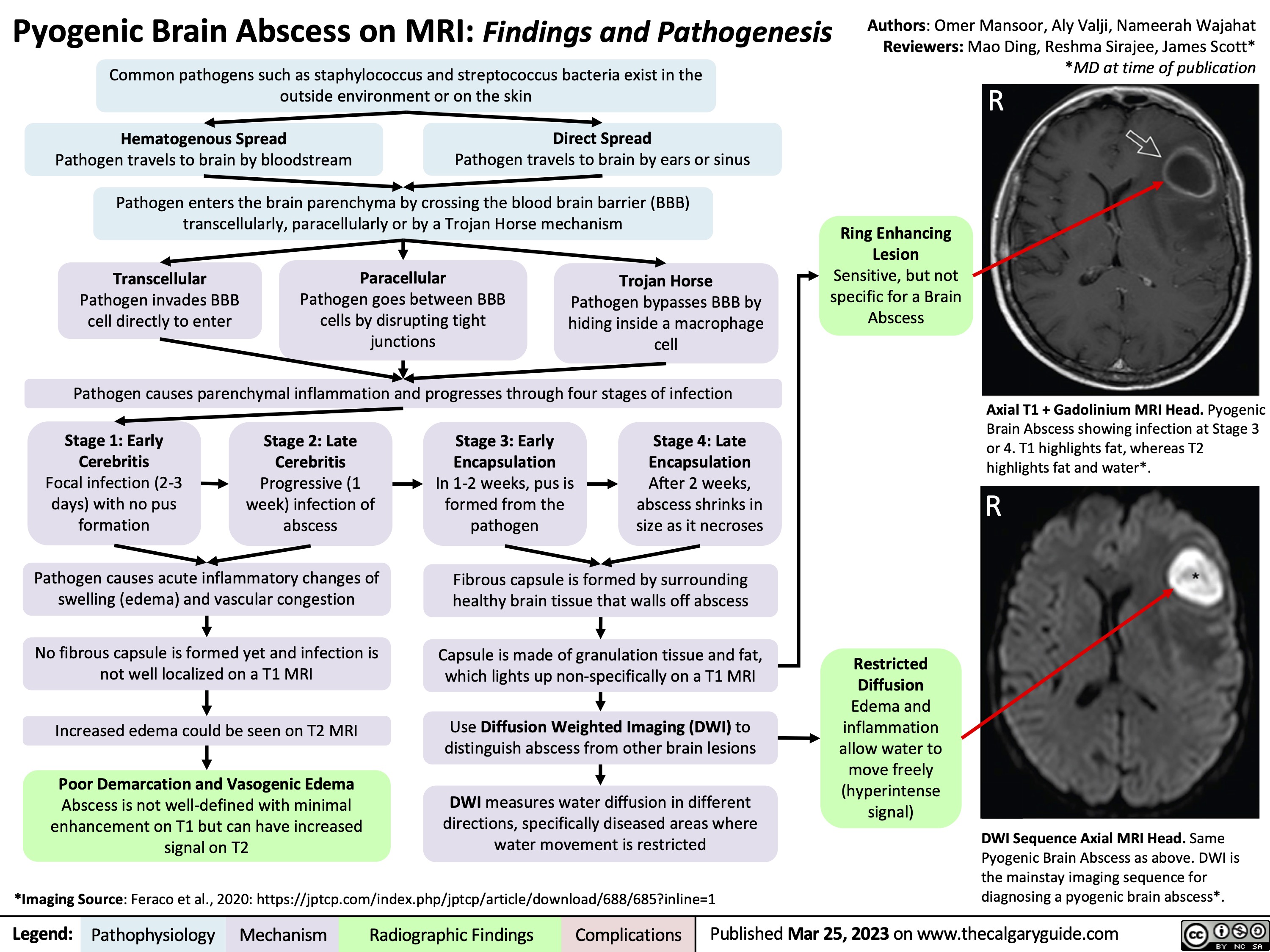

Pyogenic Brain Abscess on MRI

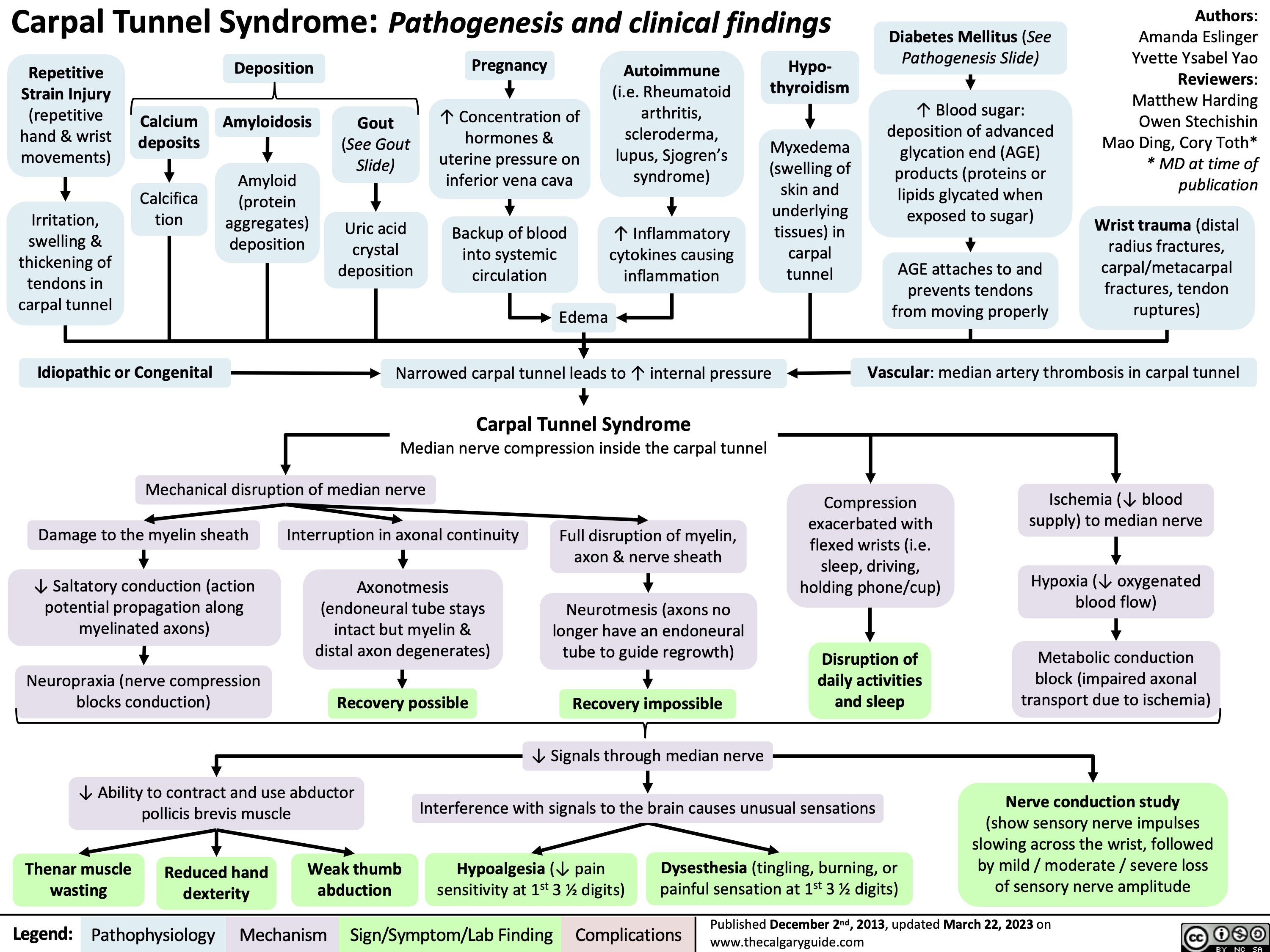

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

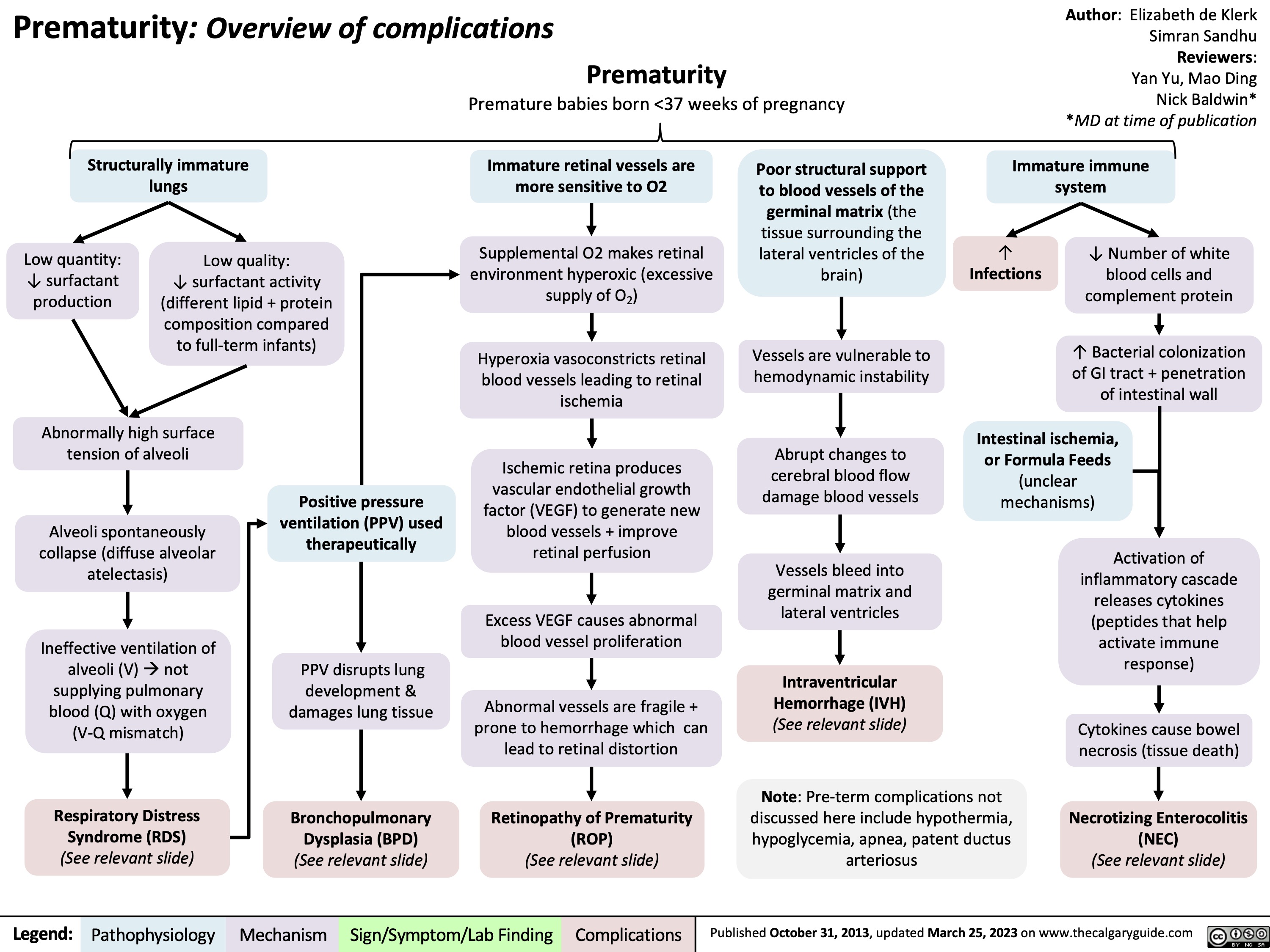

Complications of Prematurity

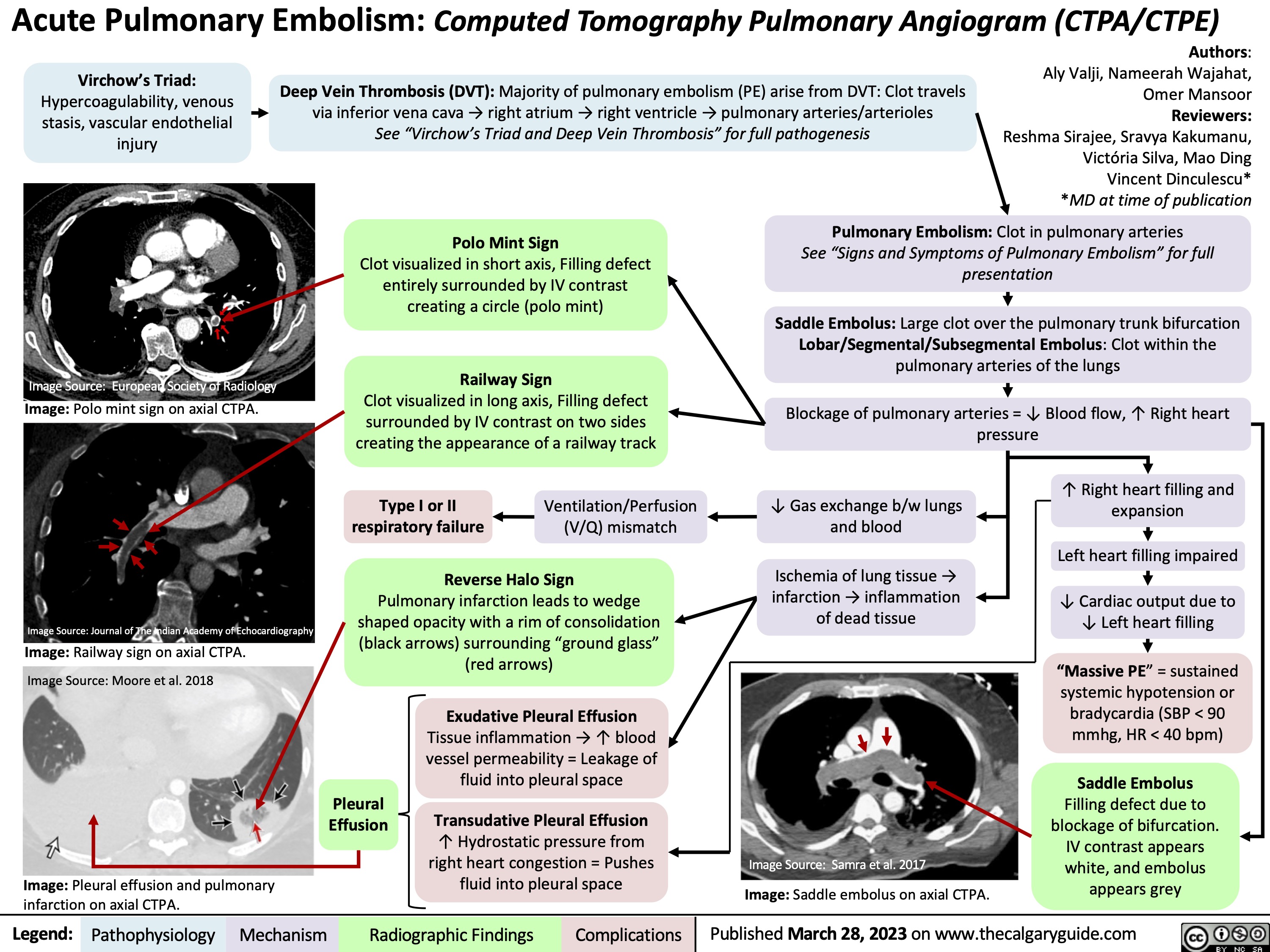

Acute Pulmonary Embolism on CTPA

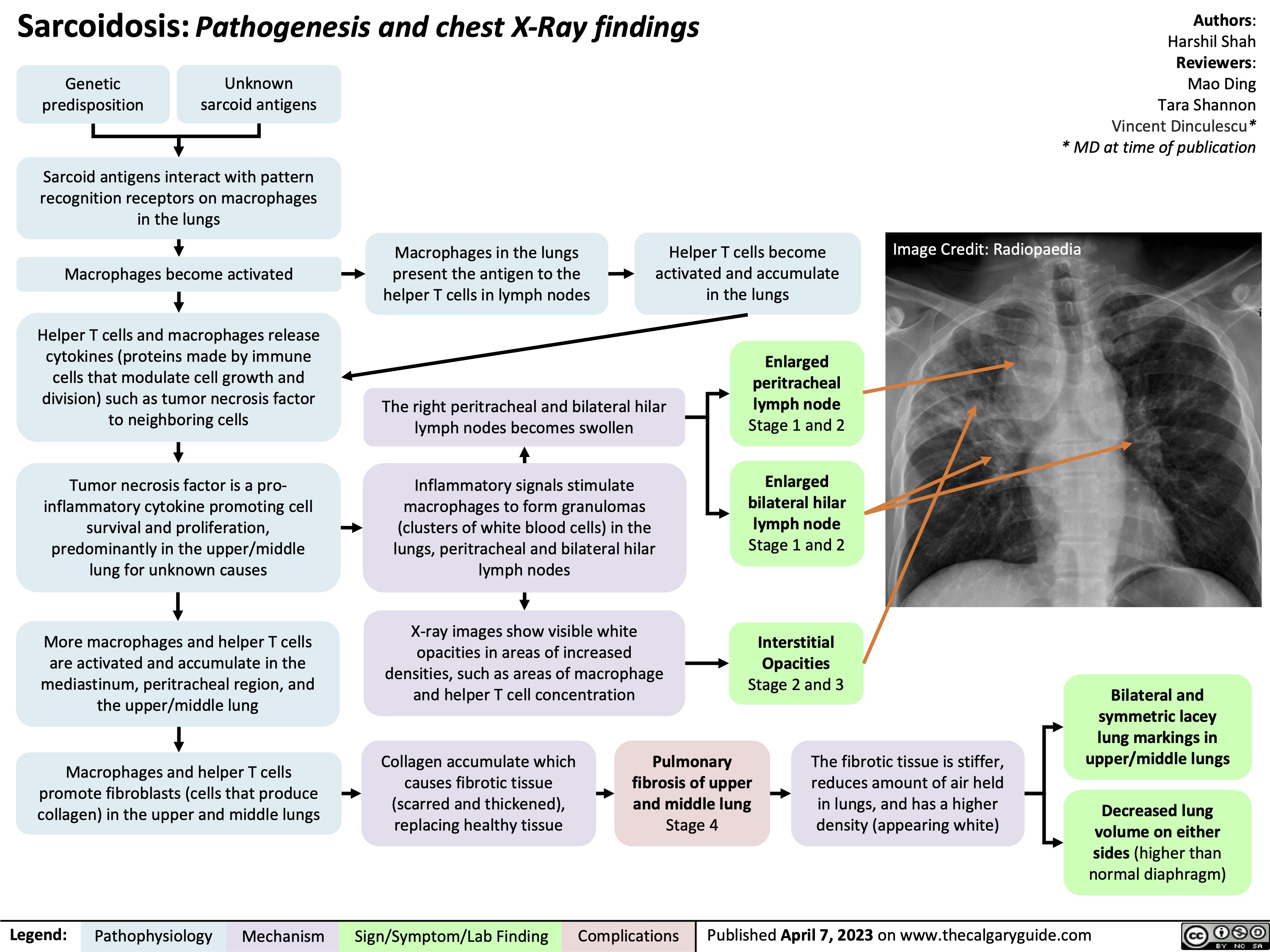

Sarcoidosis pathogenesis and CXR findings

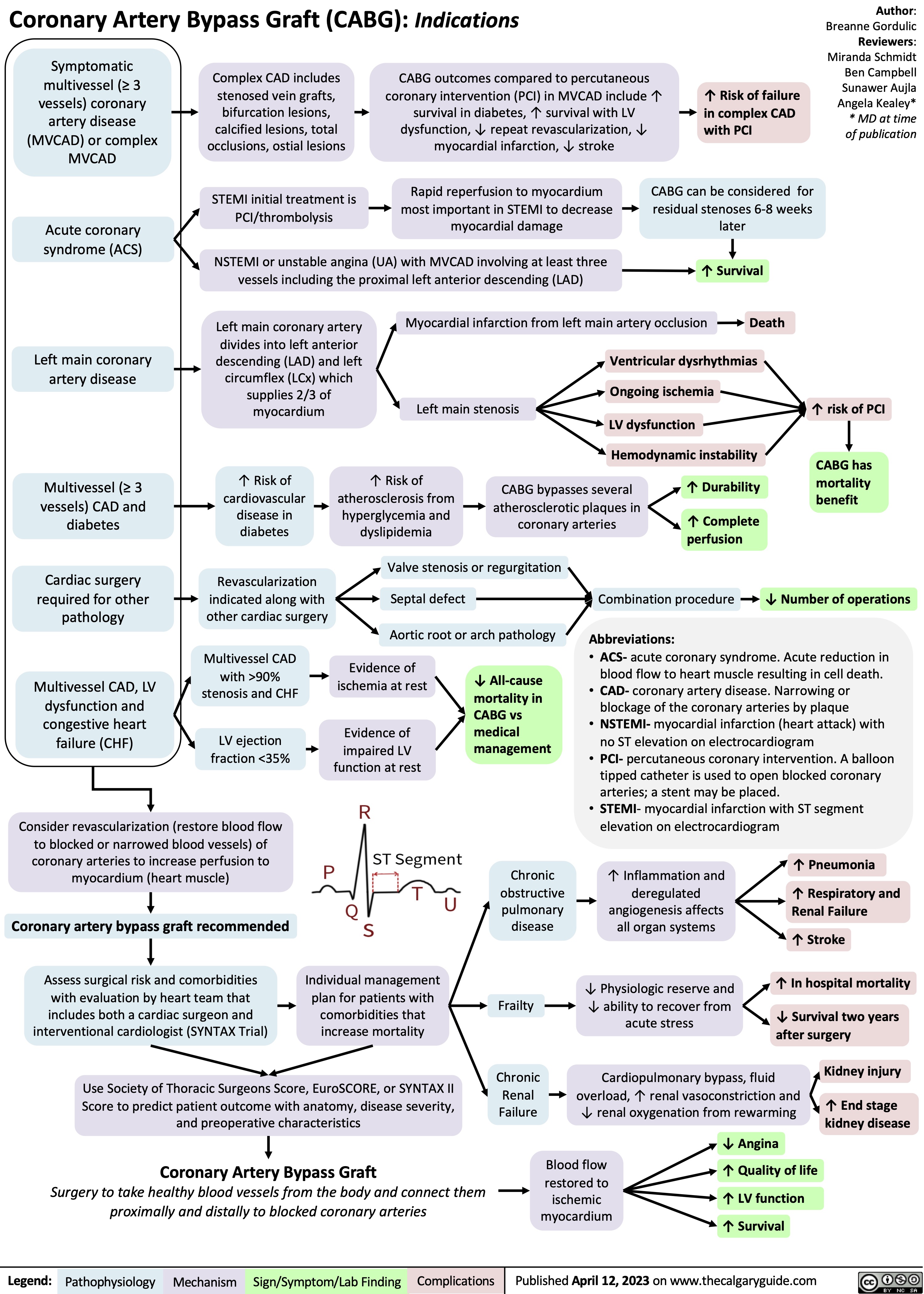

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft CABG Indications

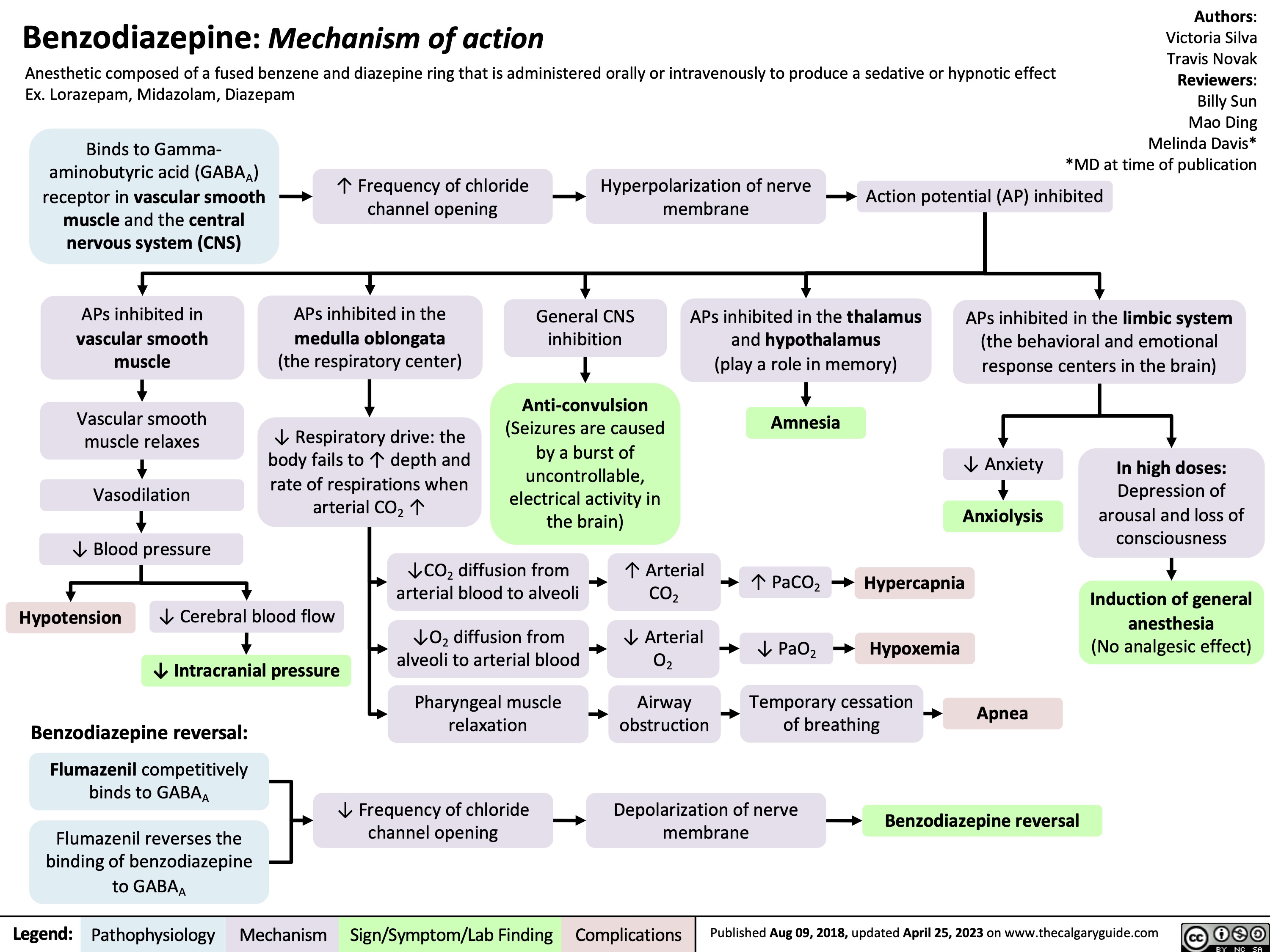

Benzodiazepine Mechanism of Action

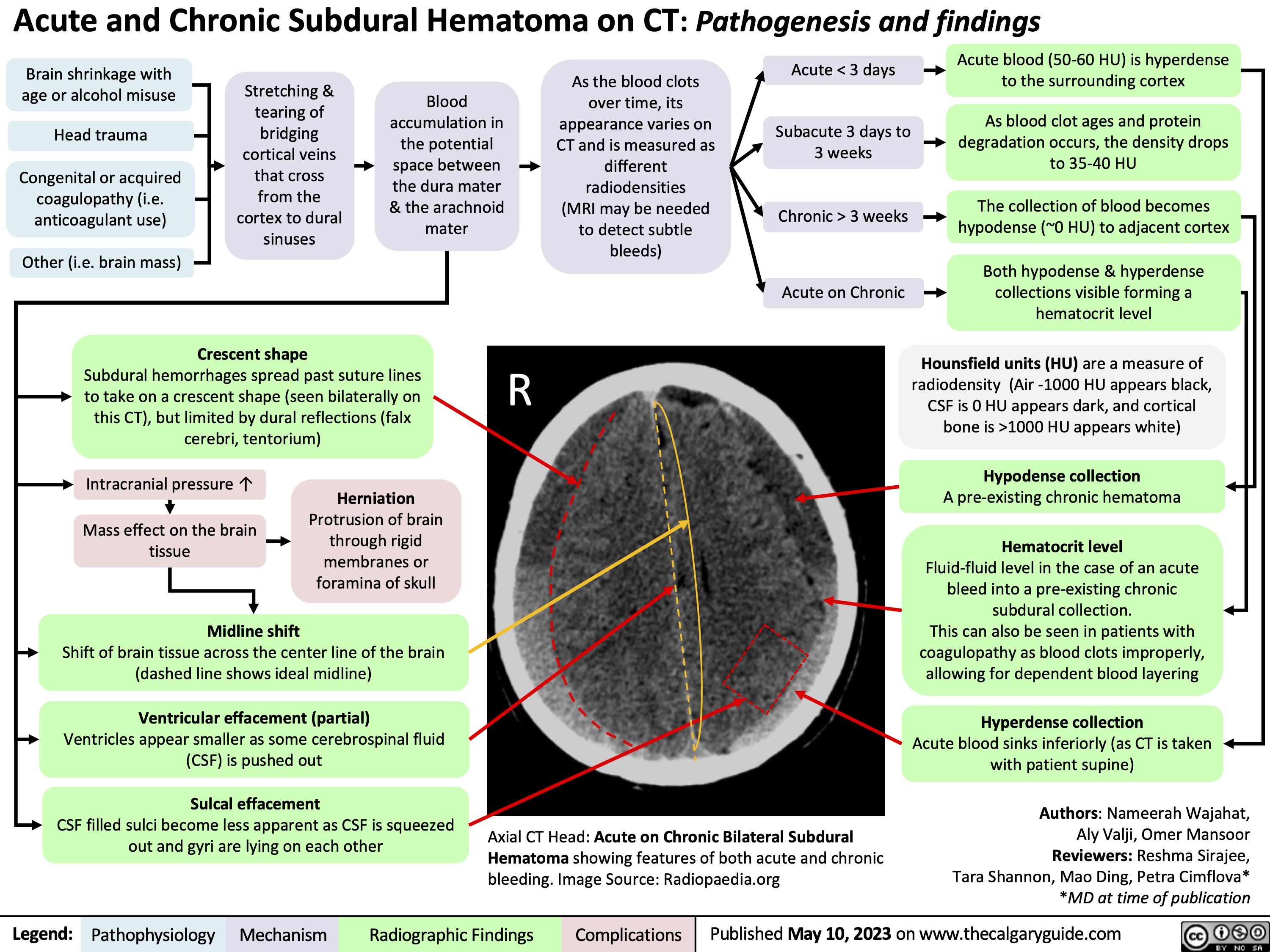

Subdural Hematoma on CT

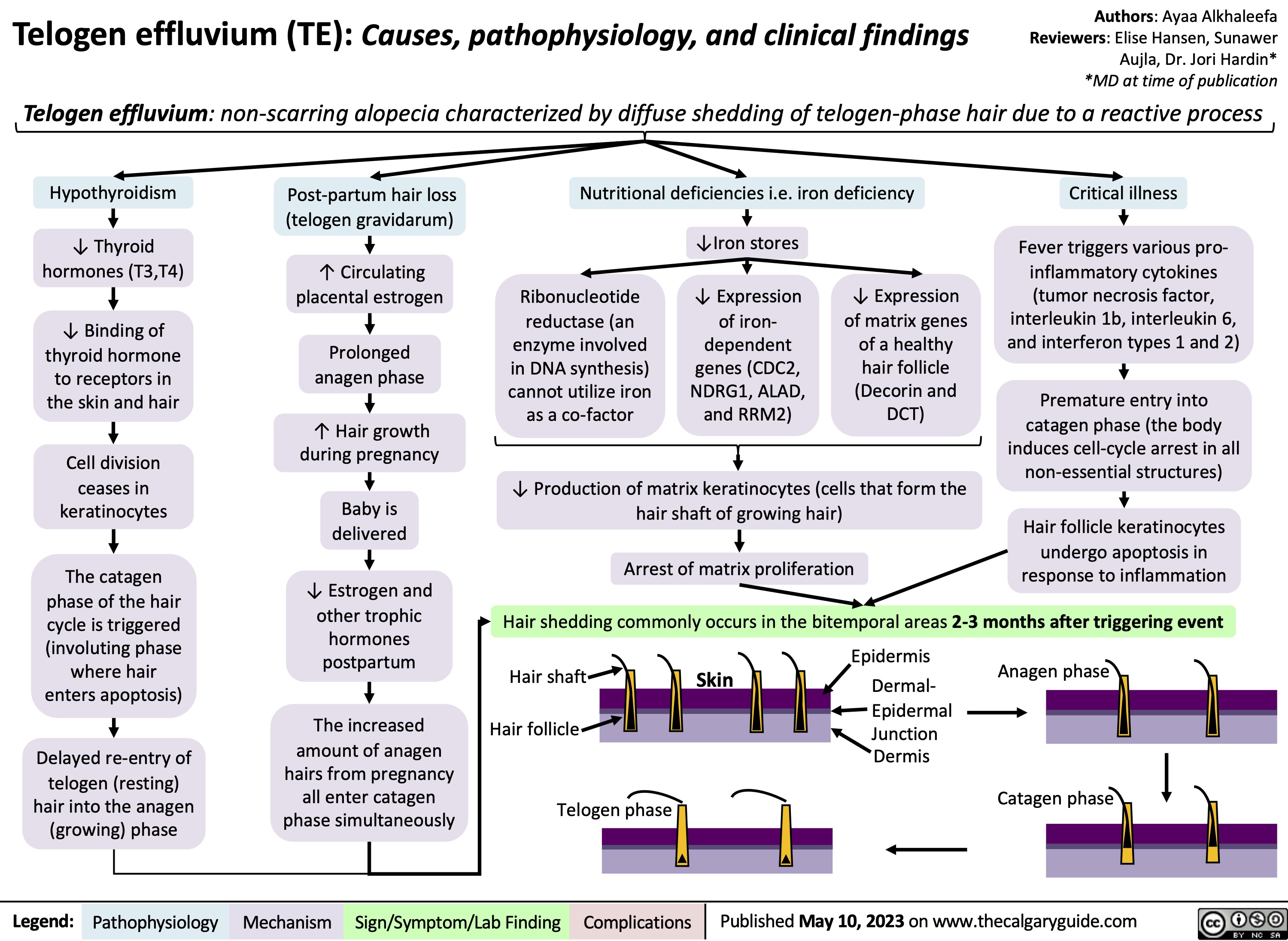

Telogen Effluvium

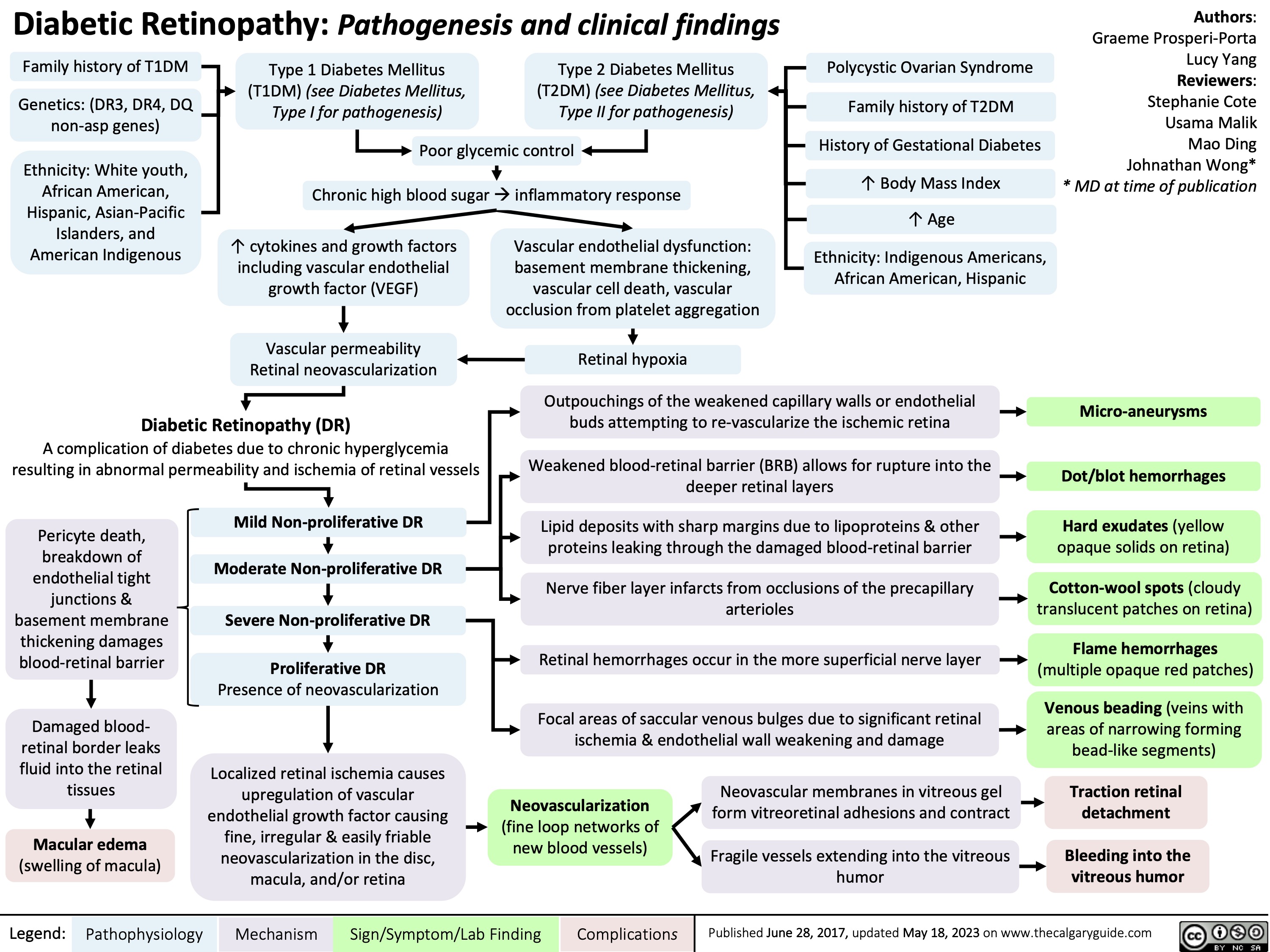

Diabetic Retinopathy

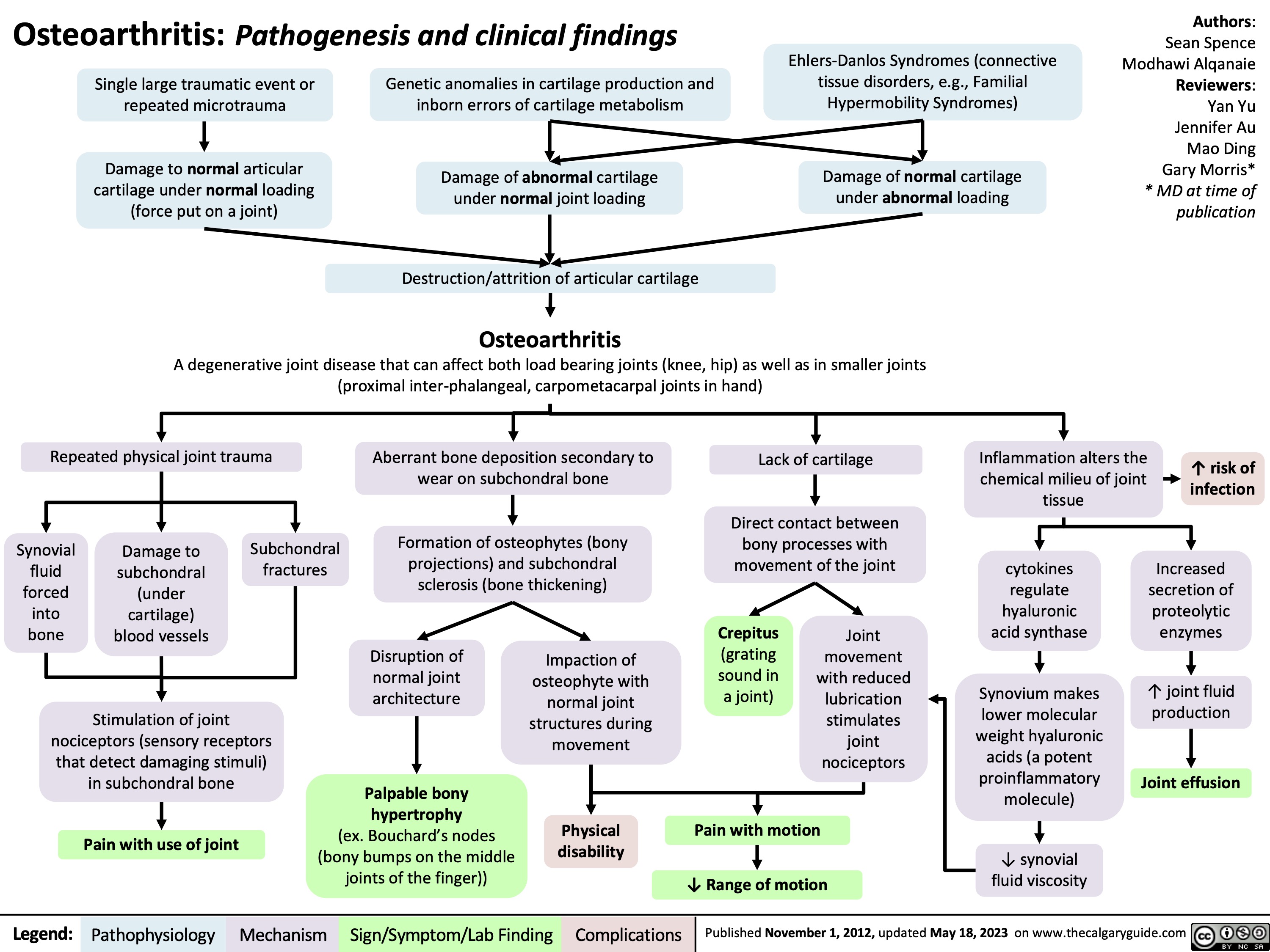

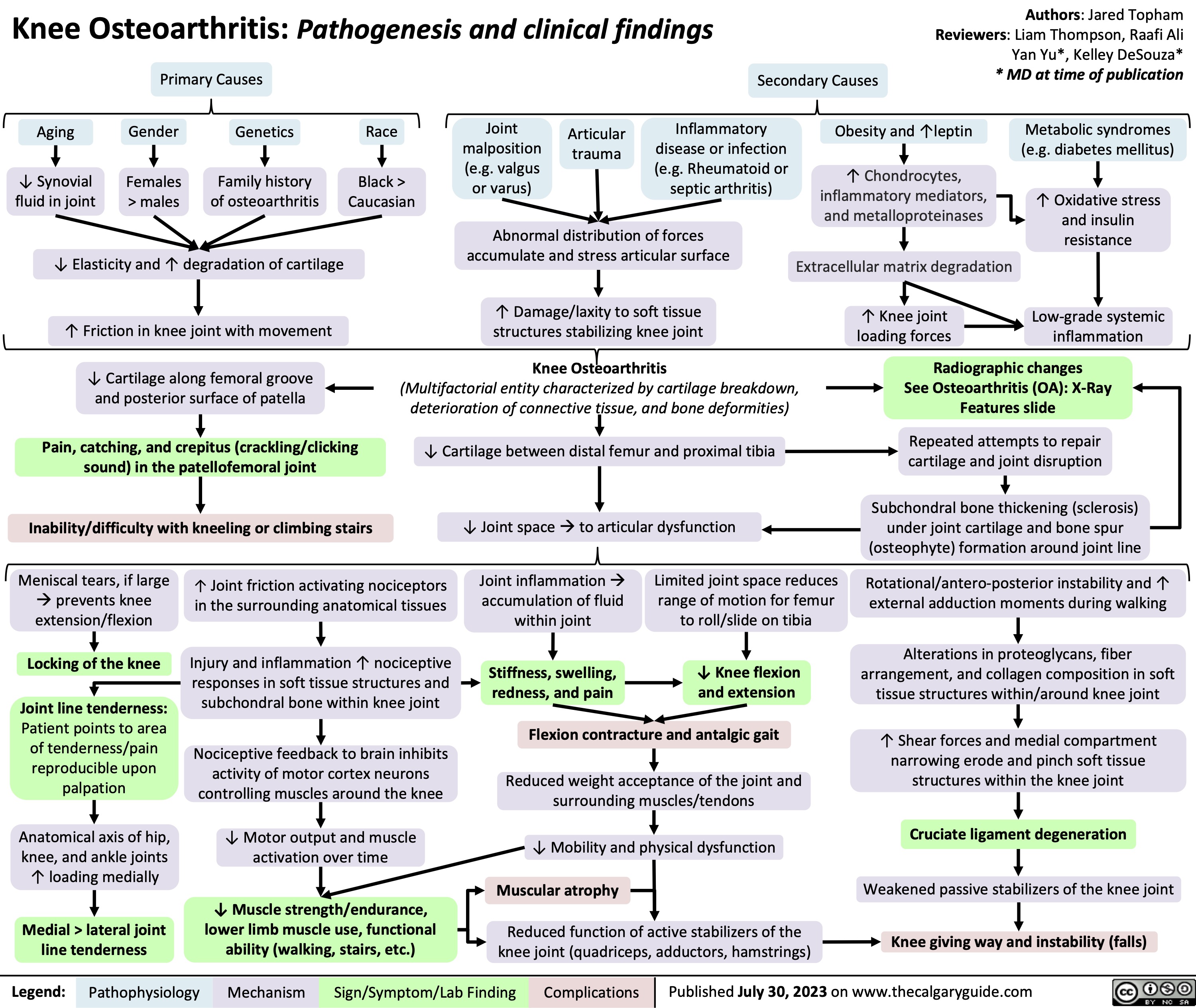

OA Clinical findings

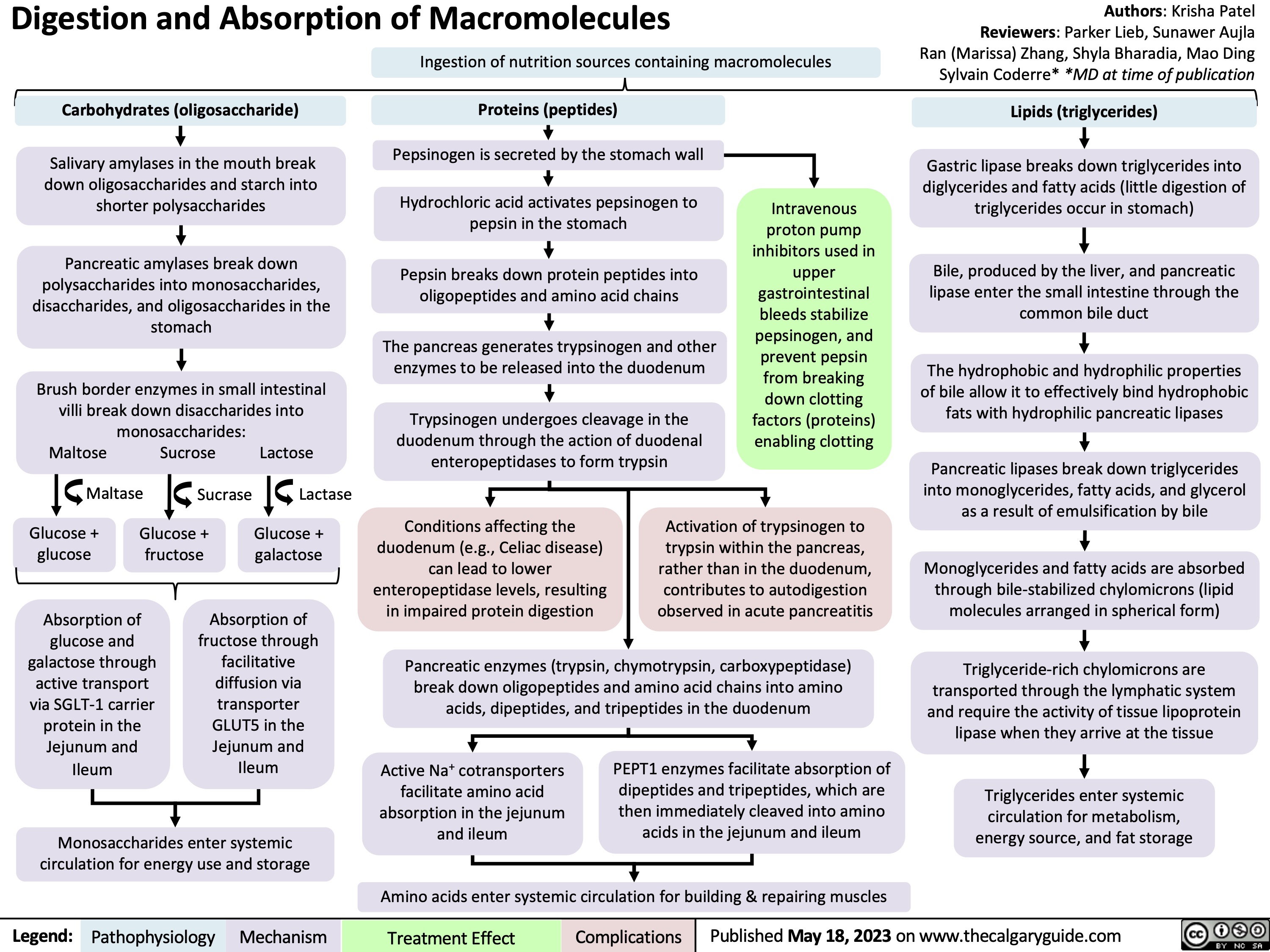

Digestion and Absorption of Macromolecules

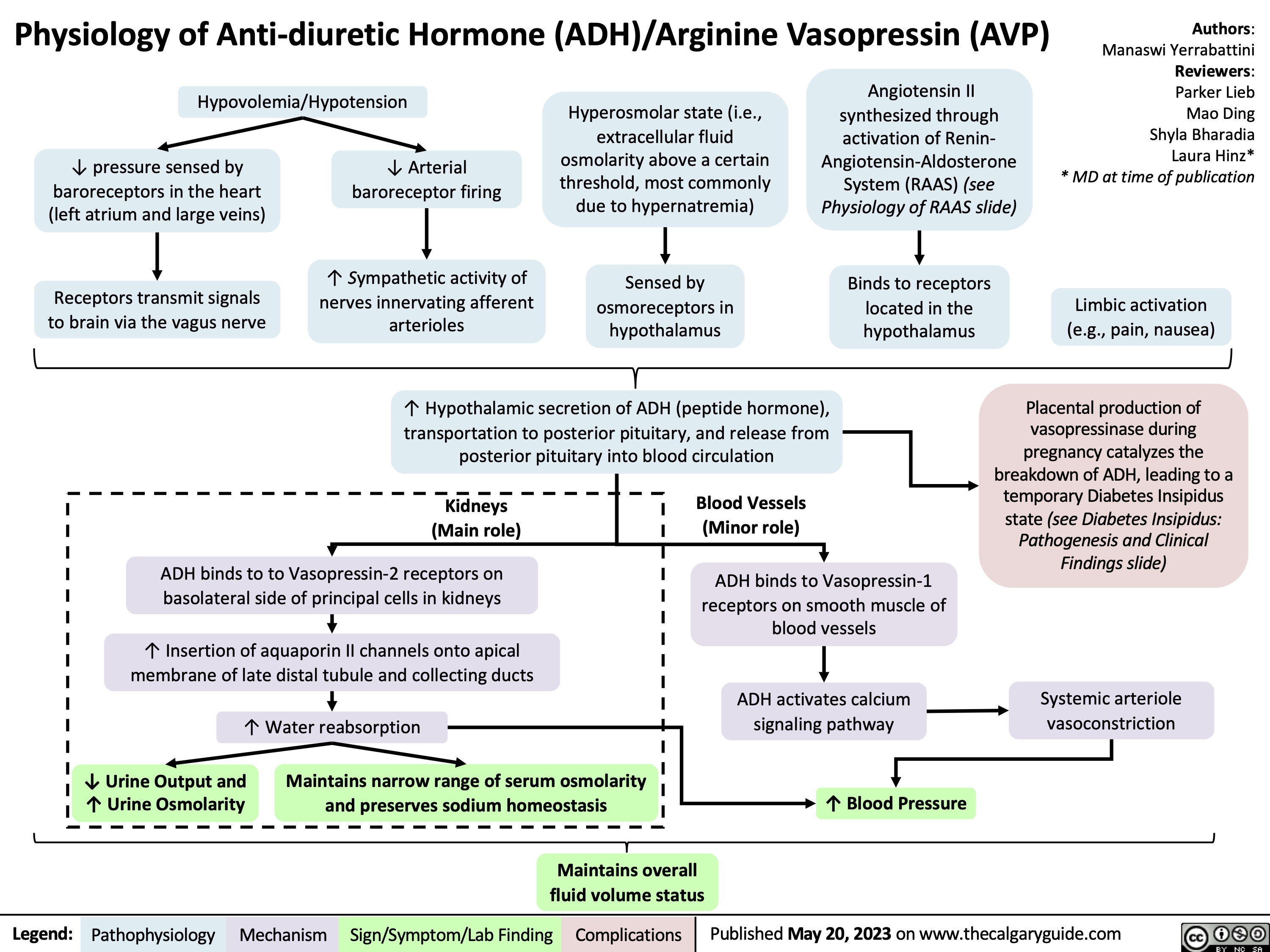

Physiology of Anti-diuretic hormone

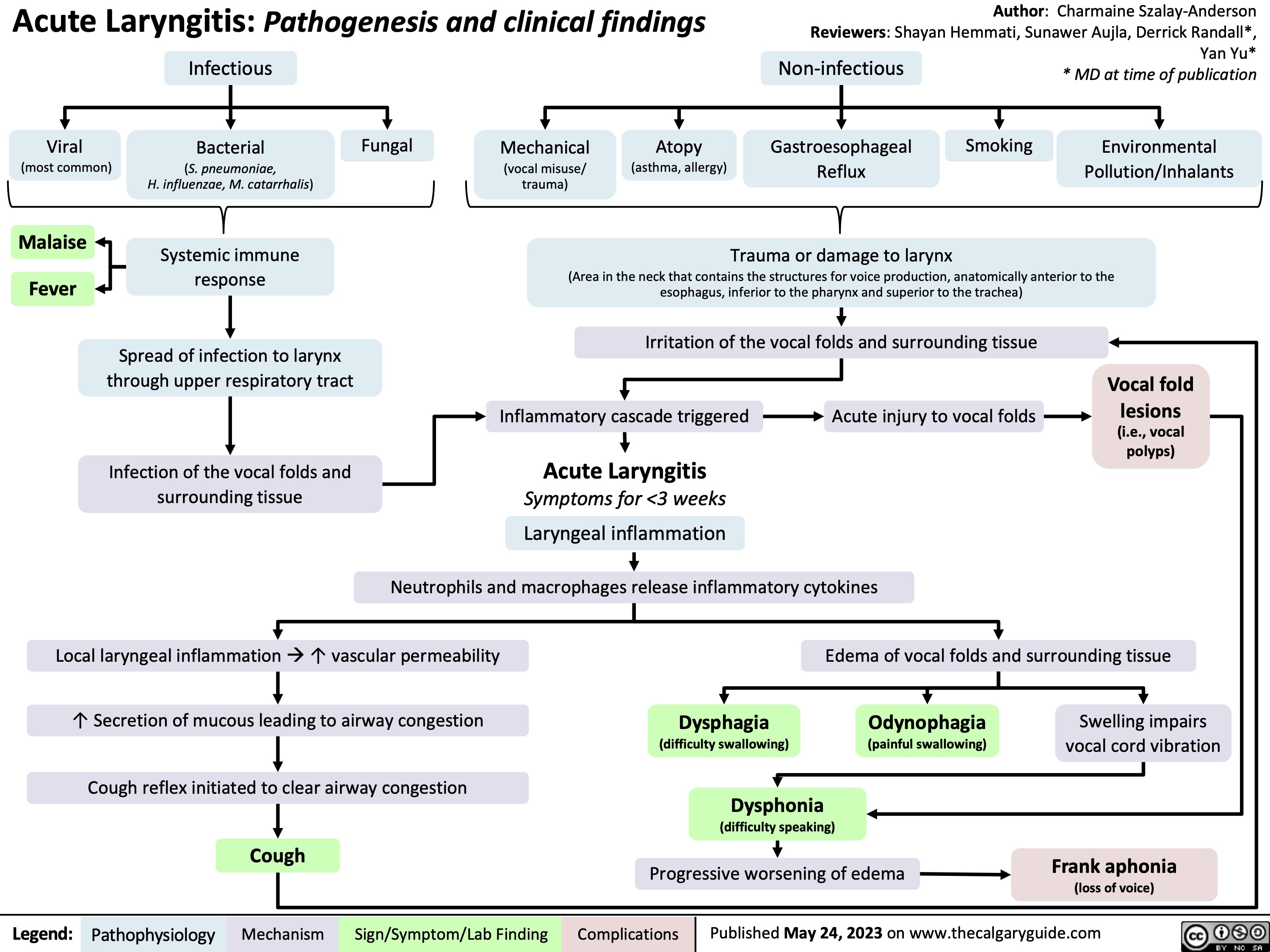

Acute Laryngitis

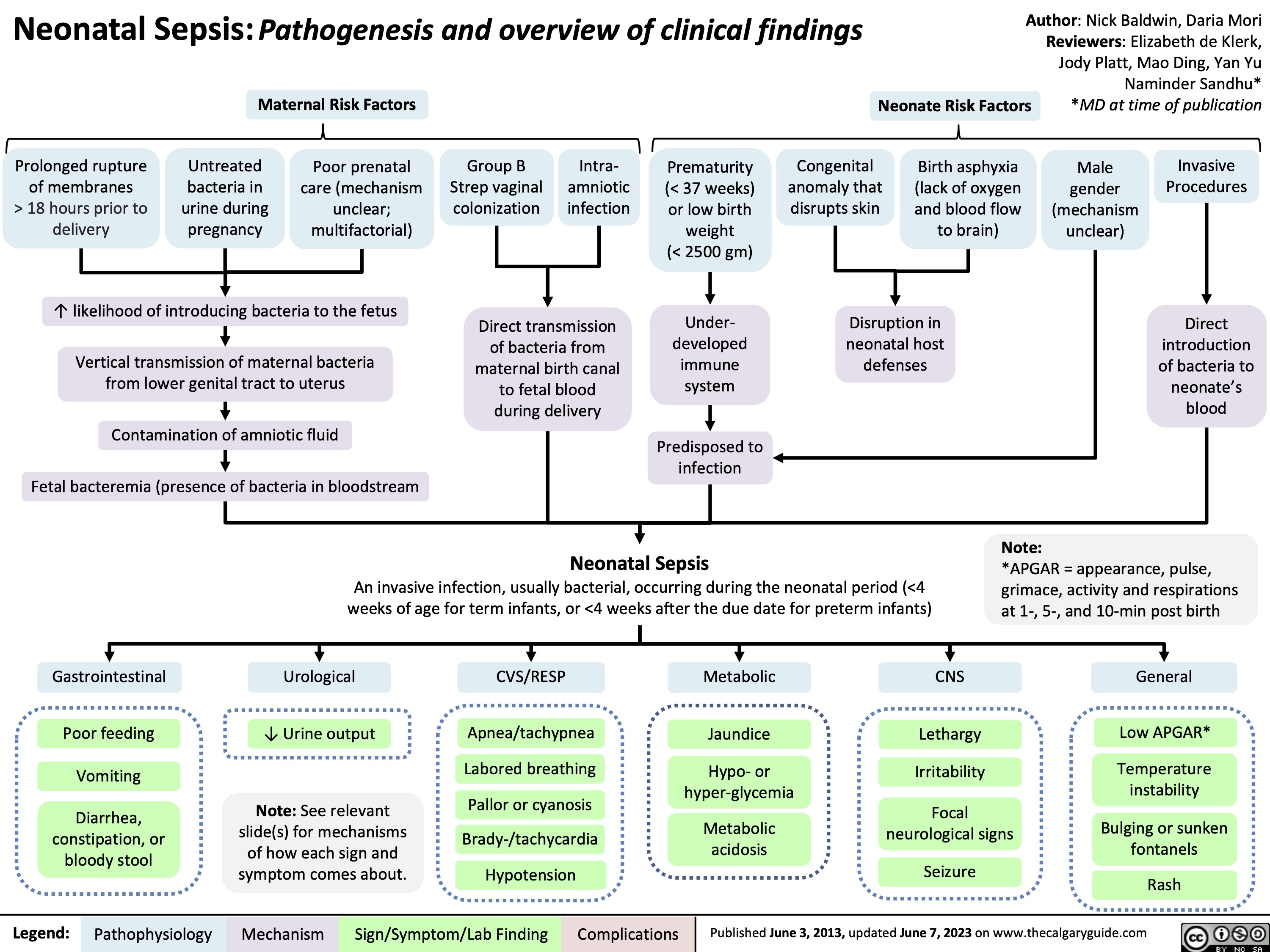

Neonatal Sepsis

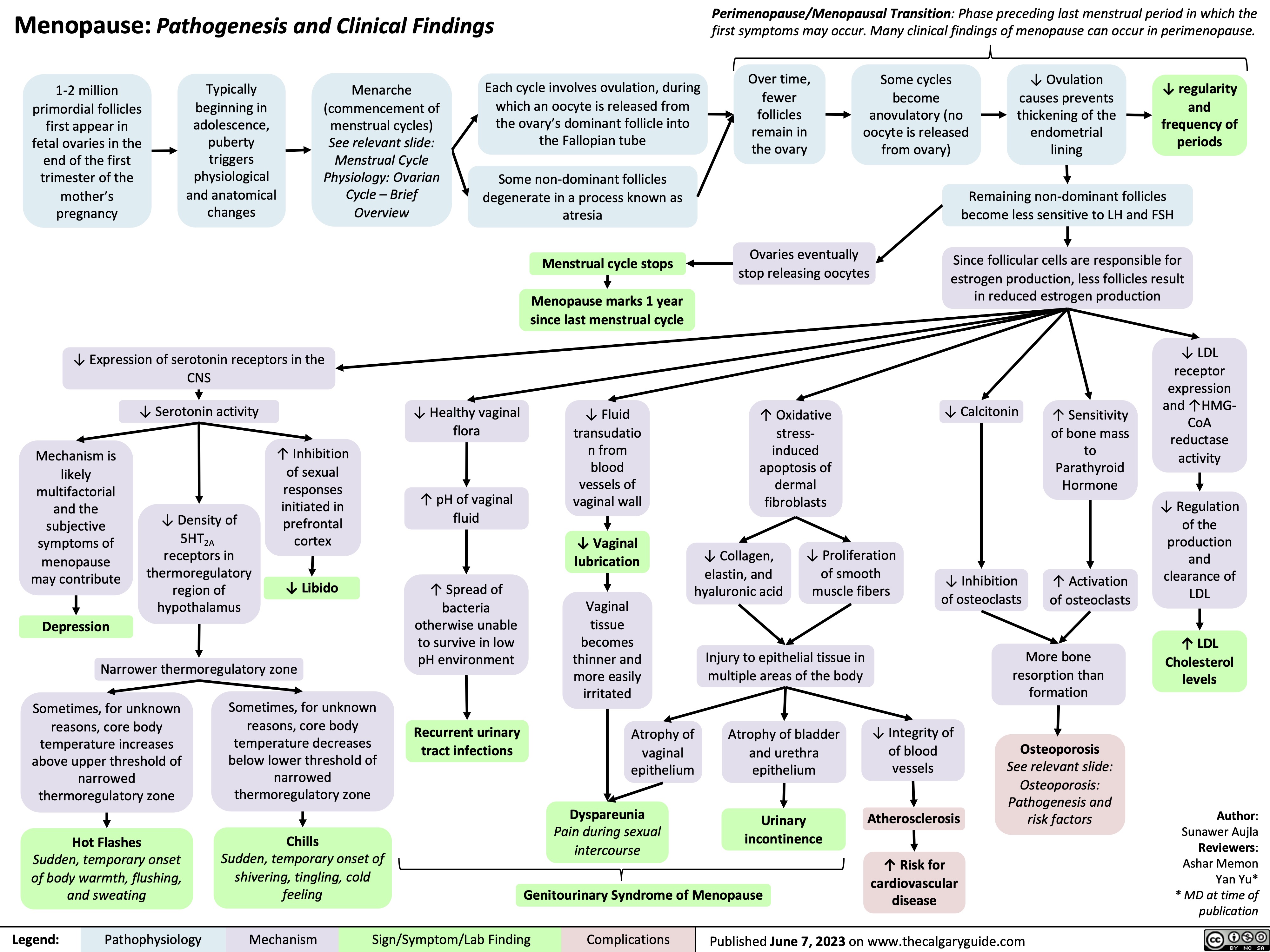

Menopause

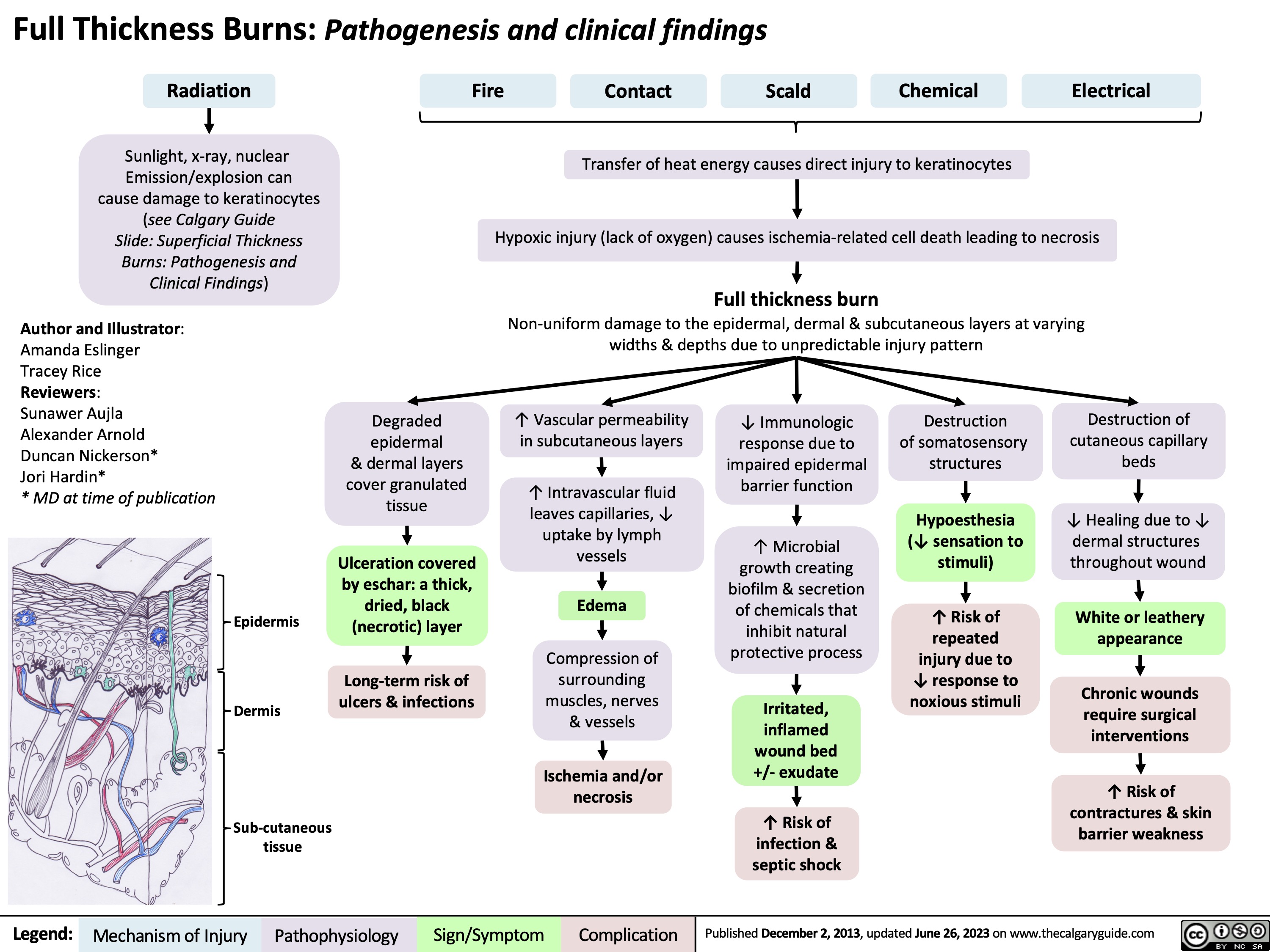

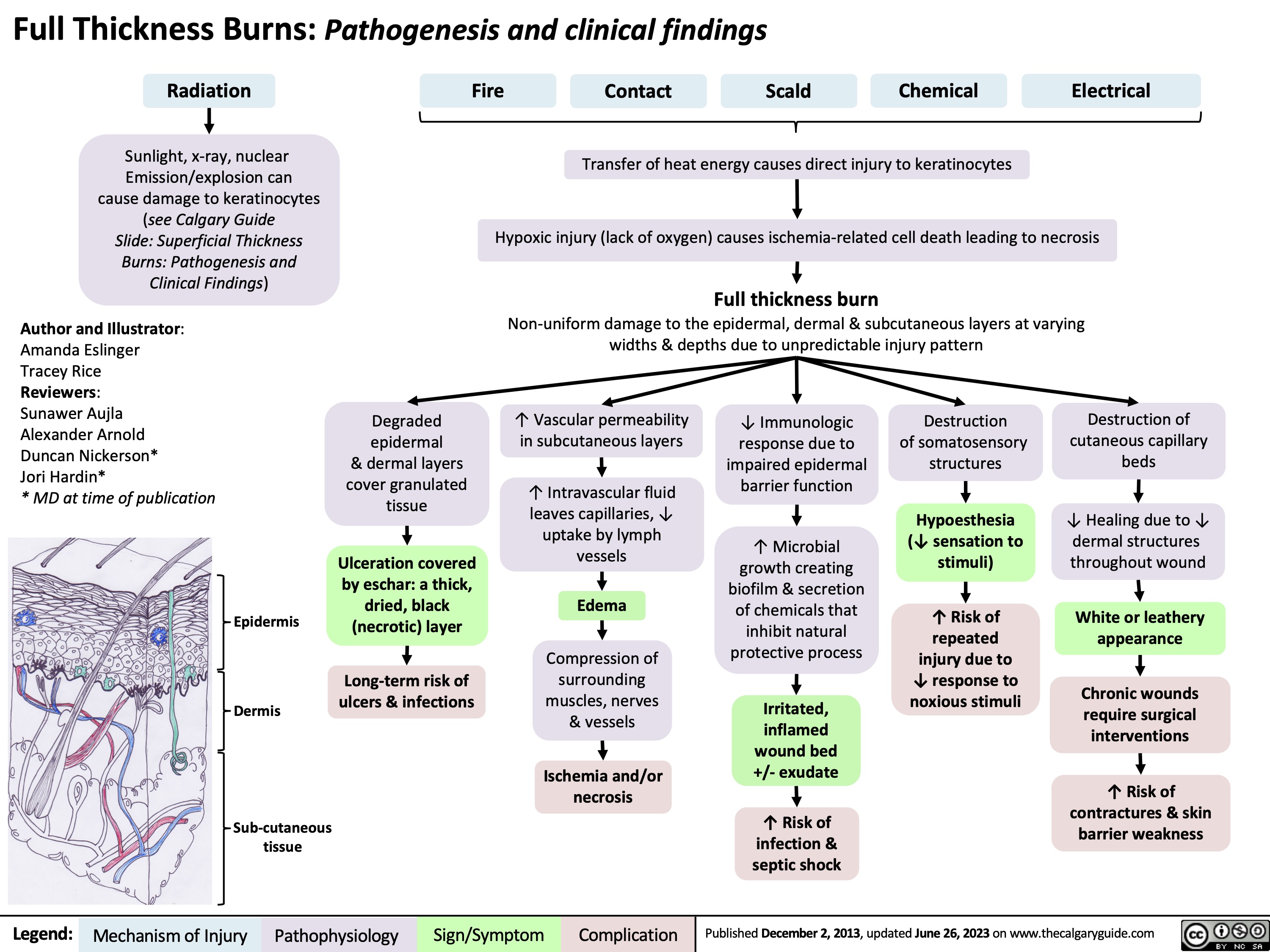

Burns - Full Thickness - Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings 2023

Burns - Full Thickness - Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

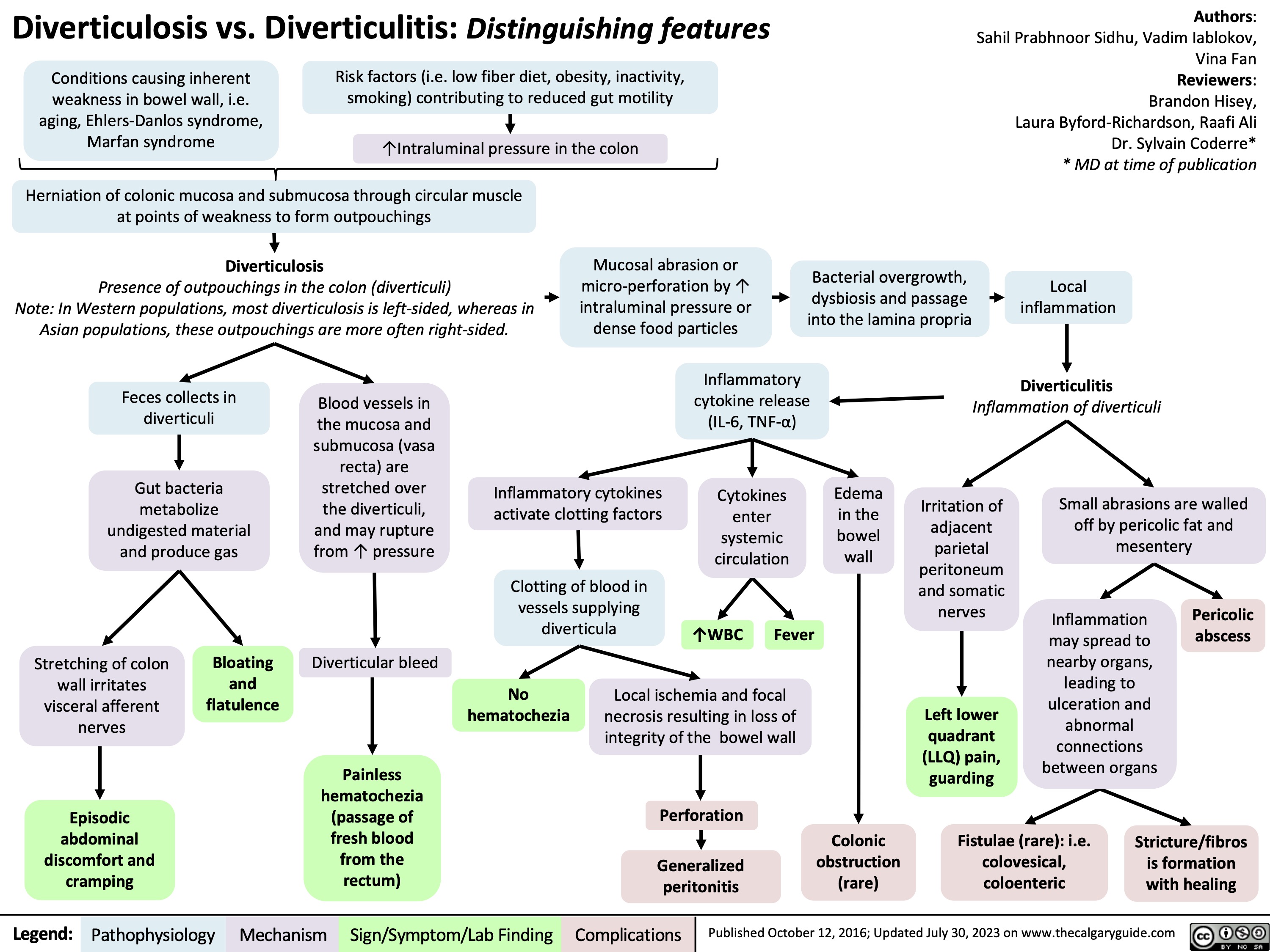

diverticulosis-vs-diverticulitis-distinguishing-features

Knee Osteoarthritis

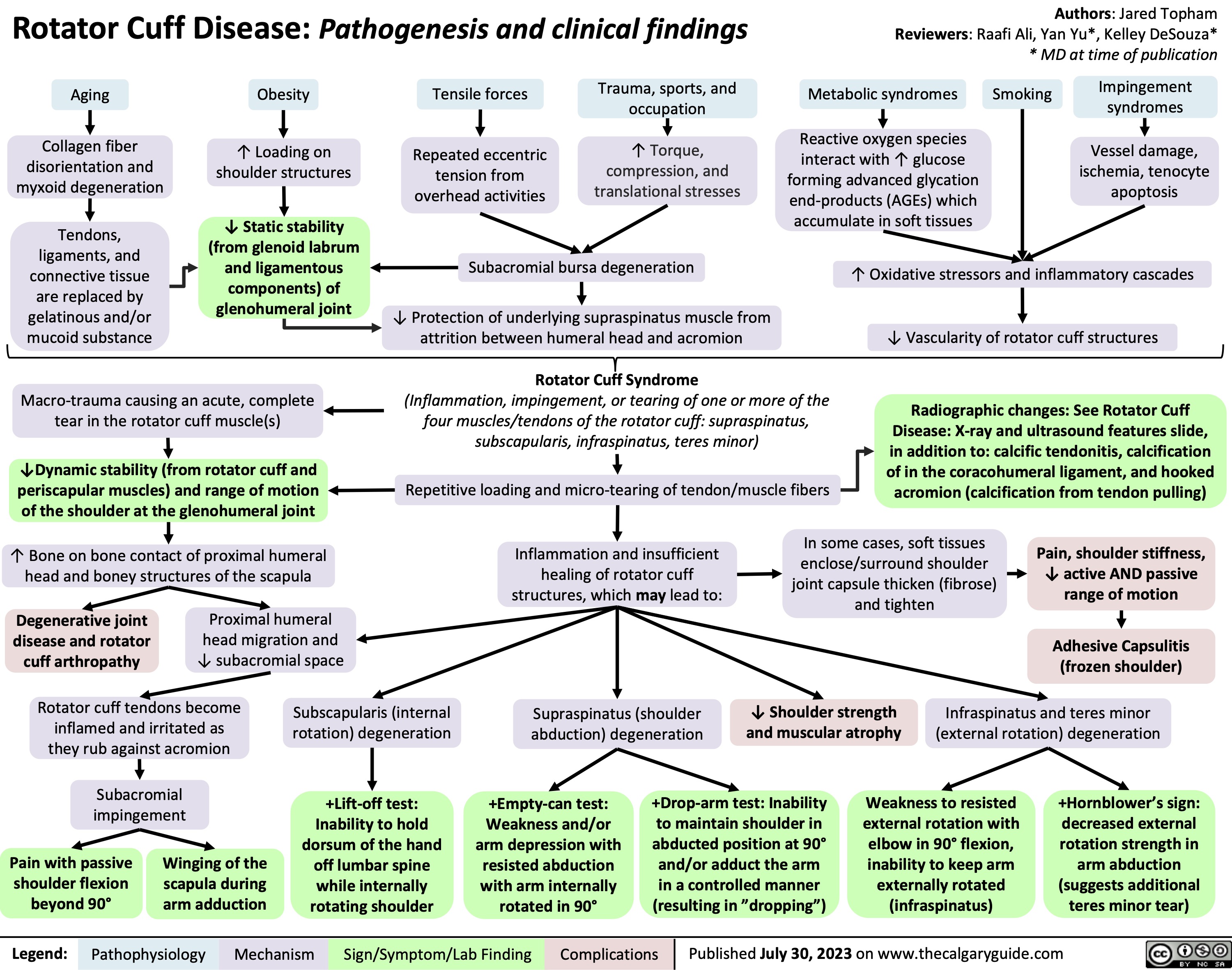

Rotator Cuff Disease

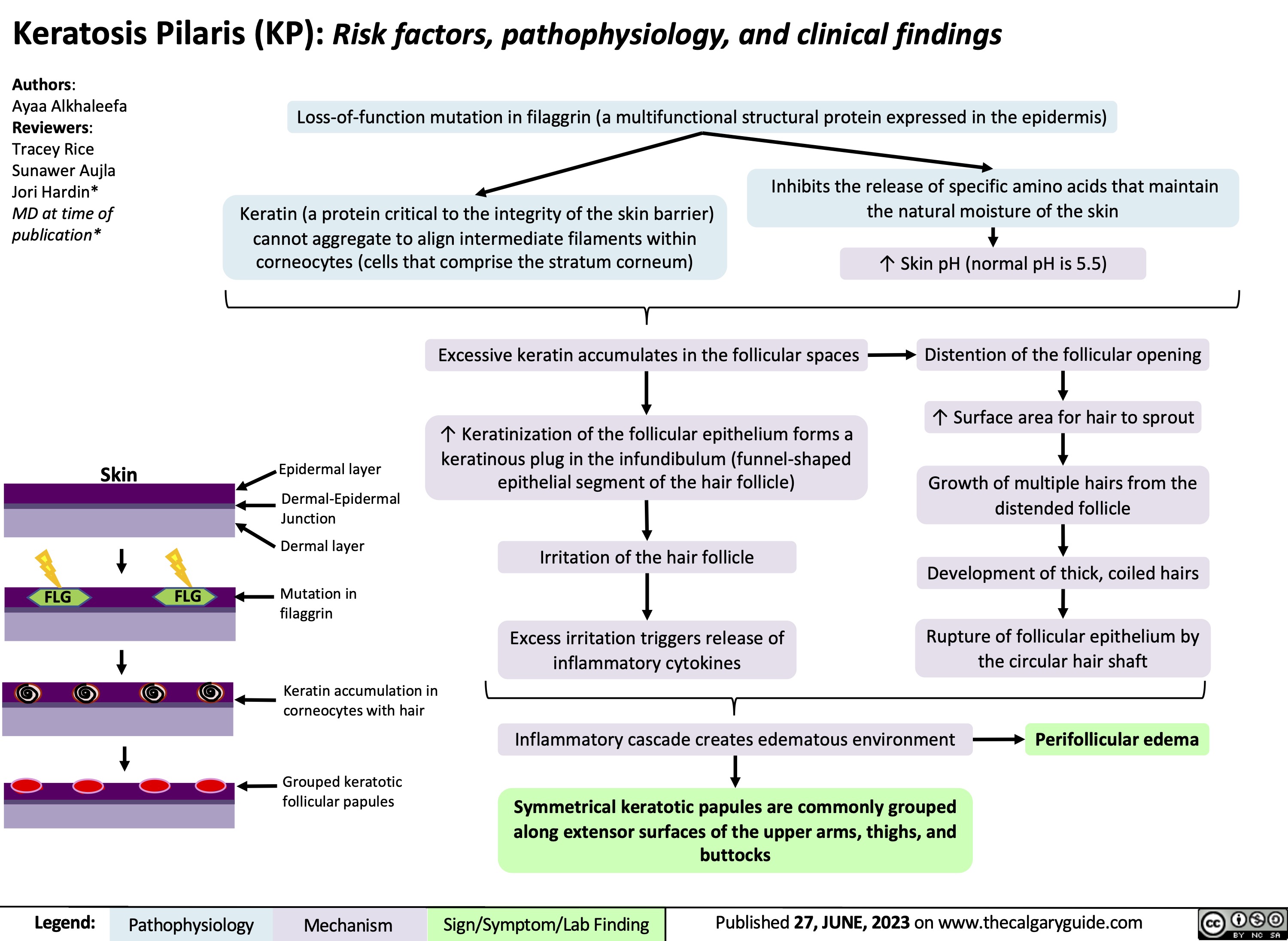

Keratosis pilaris

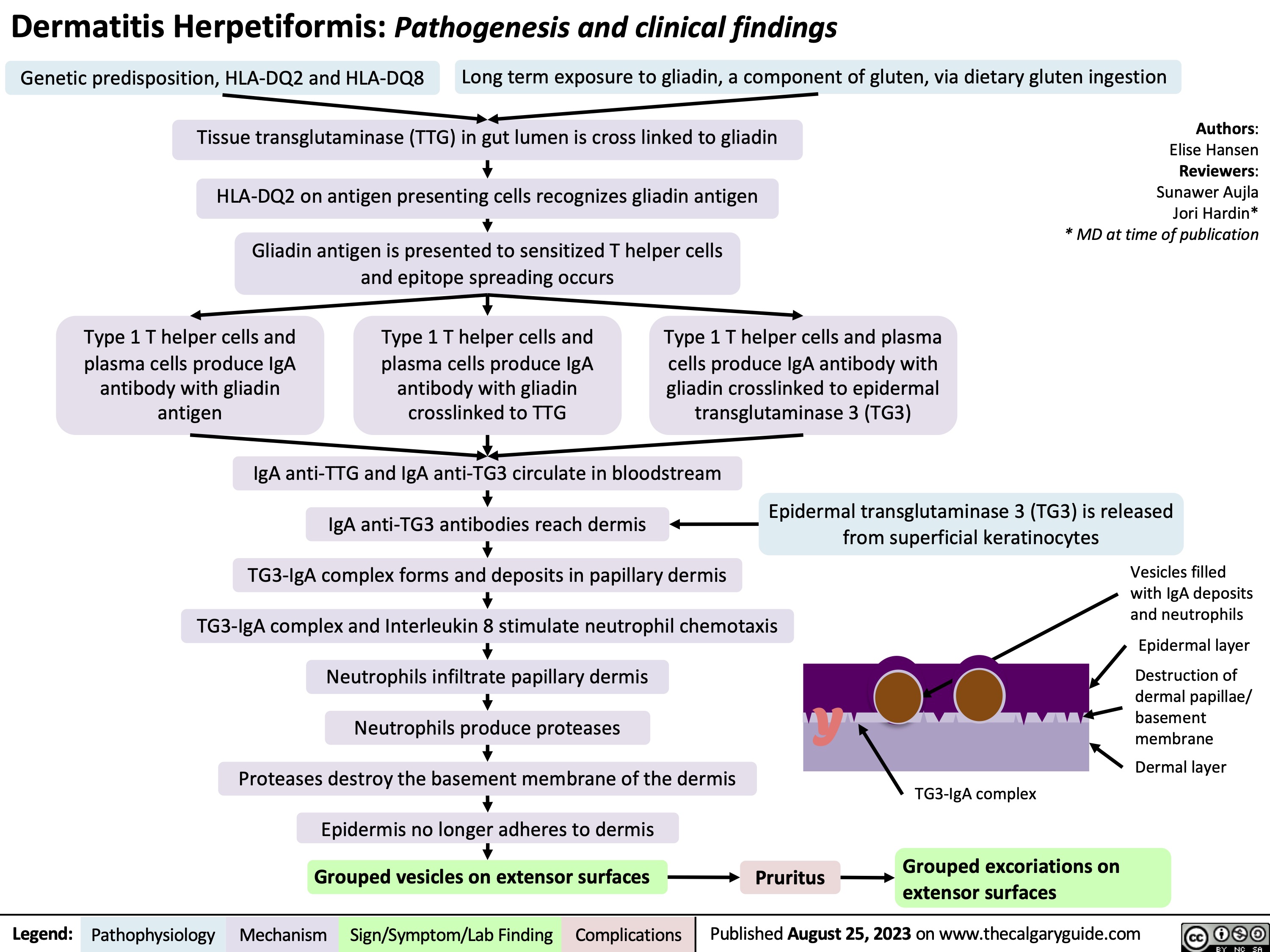

Dermatitis herpetiformis

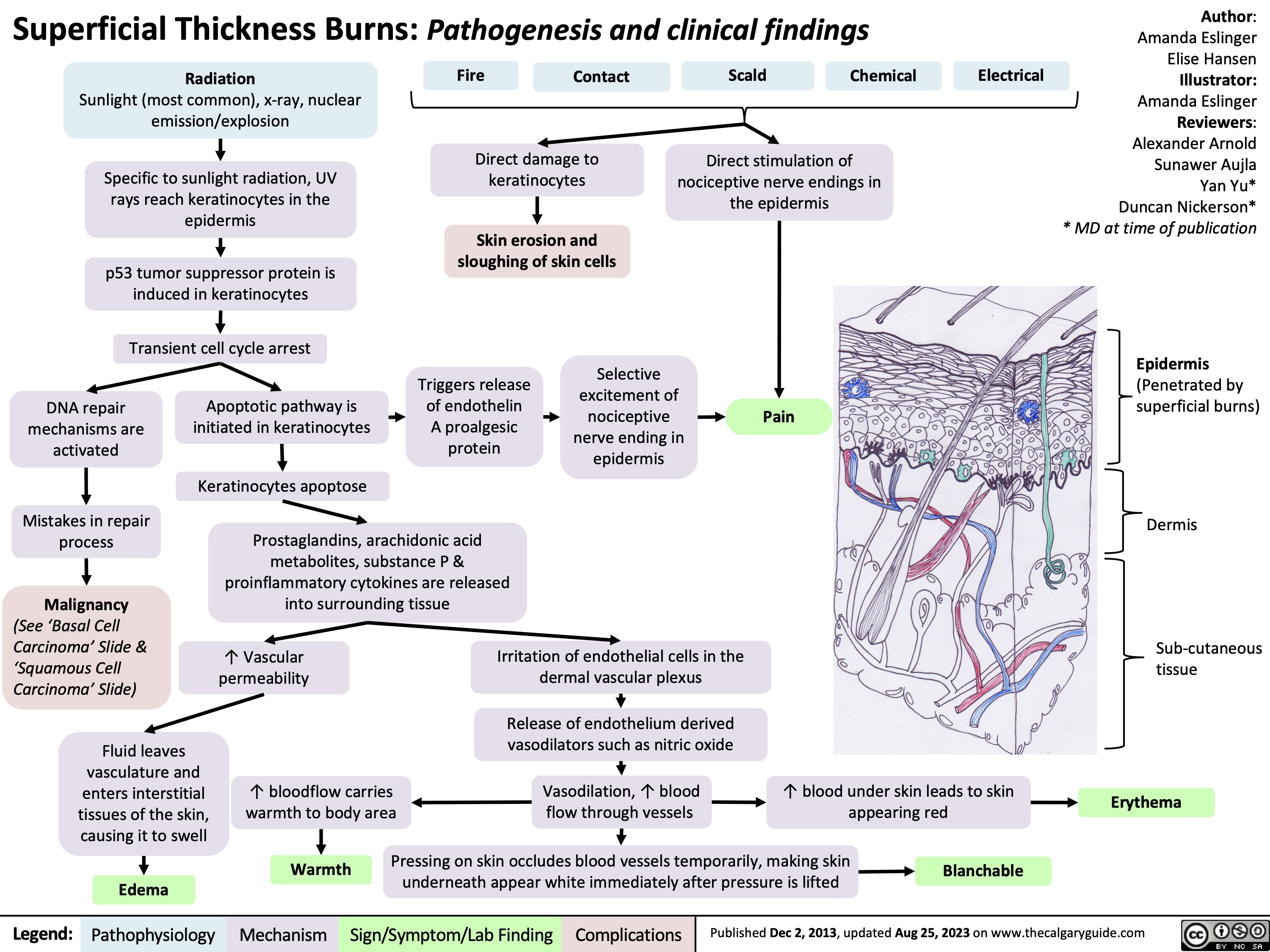

Superficial thickness burns

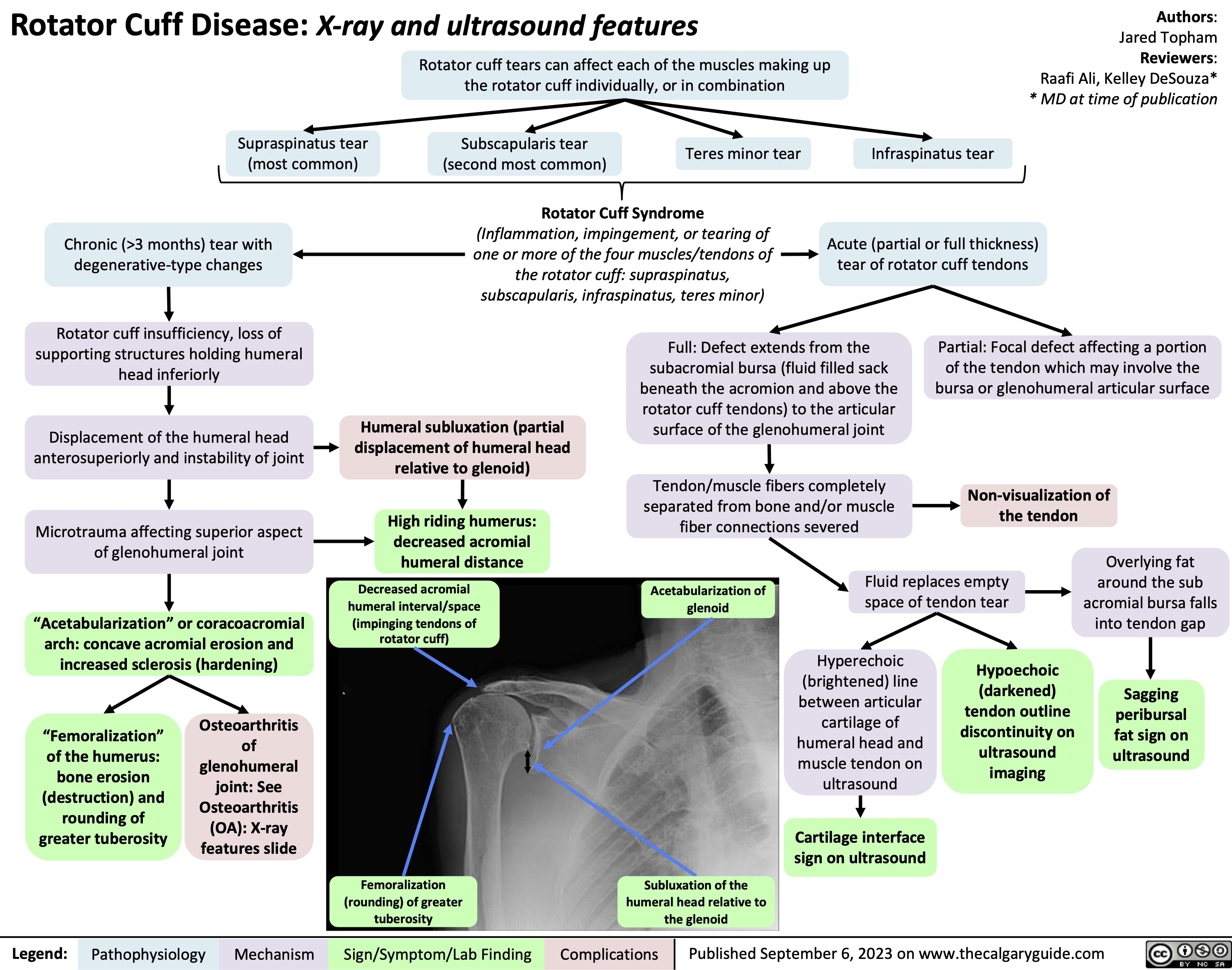

Rotator Cuff Disease Xray and Ultrasound Features

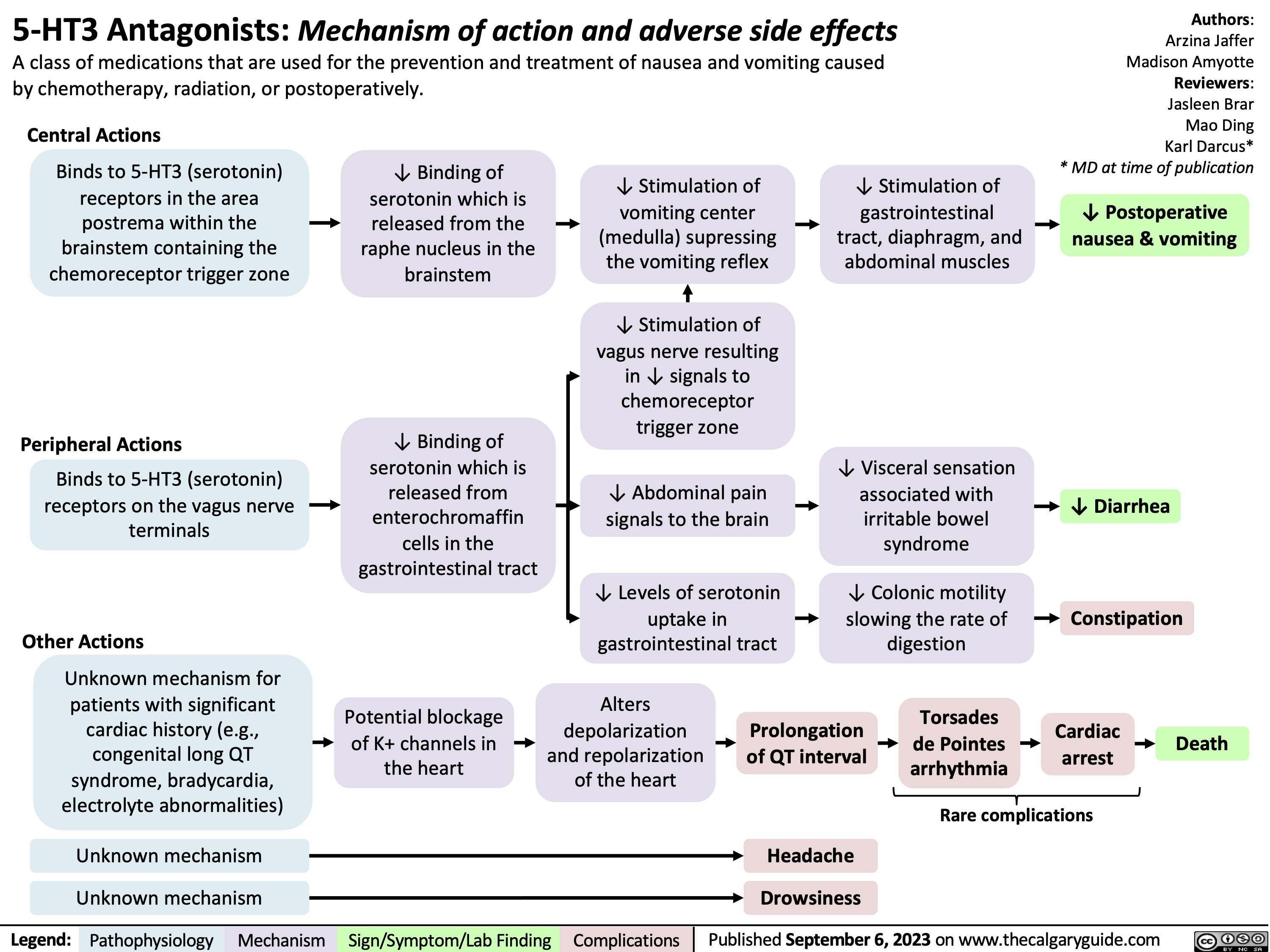

5HT3 Antagonists

Strabismus

![Strabismus: Pathogenesis and clinical findings

Microvascular dysfunction, trauma, or compression of oculomotor nerve

Oculomotor

nerve palsy: Dysfunction of the nerve innervating the superior rectus (elevation), inferior rectus (depression), medial rectus (adduction), and inferior oblique muscles (excyclotorsion)

Thyroid eye disease (see Thyroid Eye Disease slide for pathogenesis)

Inflammatory processes

Thickening & fibrosis of extraocular muscles, most commonly the inferior rectus muscle (functions to rotate the eye and depress the gaze)

Brown syndrome (congenital)

Anomalous

interaction between the trochlea and superior oblique muscle tendon

Restriction of normal movement of the superior oblique tendon through the trochlea

Trochlear palsy (Dysfunction of the trochlear nerve (CN IV))

Weakness of the superior oblique muscle innervated by CN IV (responsible for depression of the gaze and incyclotorsion & rotation of the eye)

Near reflex: convergence (eyes adduct), accommodati on (thickening of the lens) & miosis (constriction of the pupil)

Excessive accommodation in hyperopic (farsighted) eyes

Over-activation of near reflex

Accommodative esotropia

Aneurysm, infection, iatrogenic injury to cranial nerve (CN) VI

Abducens palsy: ocular motor paralysis

Failure of CN VI to develop normally in utero

Duane syndrome: congenital malformation of CN VI

Congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles (CFEOM)

Restrictive global paralysis of the extraocular muscles that control the movements of the eye

Phenotype CFEOM2

Phenotype CFEOM1 & 3

Dysfunction of the abducens

nerve (CN VI: innervates the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle which abducts the eye [turns it laterally])

Orbital fracture (fracture of the orbital floor)

Intraorbital contents (inferior rectus muscle and/or surrounding tissue) herniate through the fractured site & are entrapped

Idiopathic infantile esotropia

Intermittent exotropia

Unclear process

Exotropia: affected eye is rotated laterally

Esotropia: affected eye is rotated medially

Hypotropia: affected eye is rotated downward compared to non-affected eye

Hypertropia: affected eye is rotated upward compared to non-affected eye

Horizontal Strabismus

Two different images are received by the eye that cannot be fused together Visual cortex suppresses the input from one eye in order to avoid having diplopia

Amblyopia/lazy eye: visual cortex diminishes neural inputs from the corresponding cortical areas of affected eye

↓ Spatial awareness

Vertical Strabismus

Binocular diplopia: double vision when both eyes are open, and absent when either eye is closed

Atypical alignment of the eye

Psychosocial consequences: negative impact to mental health due to social bias or abuse, social anxiety, and difficulties with self-image

Authors: Mina Mina Lucy Yang Reviewers: Mao Ding William Stell* * MD at time of publication

↓ Visual acuity

↓ Oculomotor control

Legend:

Pathophysiology

Mechanism

Sign/Symptom/Lab Finding

Complications

Published September 6, 2023 on www.thecalgaryguide.com

Strabismus: Pathogenesis and clinical findings

Microvascular dysfunction, trauma, or compression of oculomotor nerve

Oculomotor

nerve palsy: Dysfunction of the nerve innervating the superior rectus (elevation), inferior rectus (depression), medial rectus (adduction), and inferior oblique muscles (excyclotorsion)

Thyroid eye disease (see Thyroid Eye Disease slide for pathogenesis)

Inflammatory processes

Thickening & fibrosis of extraocular muscles, most commonly the inferior rectus muscle (functions to rotate the eye and depress the gaze)

Brown syndrome (congenital)

Anomalous

interaction between the trochlea and superior oblique muscle tendon

Restriction of normal movement of the superior oblique tendon through the trochlea

Trochlear palsy (Dysfunction of the trochlear nerve (CN IV))

Weakness of the superior oblique muscle innervated by CN IV (responsible for depression of the gaze and incyclotorsion & rotation of the eye)

Near reflex: convergence (eyes adduct), accommodati on (thickening of the lens) & miosis (constriction of the pupil)

Excessive accommodation in hyperopic (farsighted) eyes

Over-activation of near reflex

Accommodative esotropia

Aneurysm, infection, iatrogenic injury to cranial nerve (CN) VI

Abducens palsy: ocular motor paralysis

Failure of CN VI to develop normally in utero

Duane syndrome: congenital malformation of CN VI

Congenital fibrosis of the extraocular muscles (CFEOM)

Restrictive global paralysis of the extraocular muscles that control the movements of the eye

Phenotype CFEOM2

Phenotype CFEOM1 & 3

Dysfunction of the abducens

nerve (CN VI: innervates the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle which abducts the eye [turns it laterally])

Orbital fracture (fracture of the orbital floor)

Intraorbital contents (inferior rectus muscle and/or surrounding tissue) herniate through the fractured site & are entrapped

Idiopathic infantile esotropia

Intermittent exotropia

Unclear process

Exotropia: affected eye is rotated laterally

Esotropia: affected eye is rotated medially

Hypotropia: affected eye is rotated downward compared to non-affected eye

Hypertropia: affected eye is rotated upward compared to non-affected eye

Horizontal Strabismus

Two different images are received by the eye that cannot be fused together Visual cortex suppresses the input from one eye in order to avoid having diplopia

Amblyopia/lazy eye: visual cortex diminishes neural inputs from the corresponding cortical areas of affected eye

↓ Spatial awareness

Vertical Strabismus

Binocular diplopia: double vision when both eyes are open, and absent when either eye is closed

Atypical alignment of the eye

Psychosocial consequences: negative impact to mental health due to social bias or abuse, social anxiety, and difficulties with self-image

Authors: Mina Mina Lucy Yang Reviewers: Mao Ding William Stell* * MD at time of publication

↓ Visual acuity

↓ Oculomotor control

Legend:

Pathophysiology

Mechanism

Sign/Symptom/Lab Finding

Complications

Published September 6, 2023 on www.thecalgaryguide.com](https://calgaryguide.ucalgary.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Strabismus.jpg)

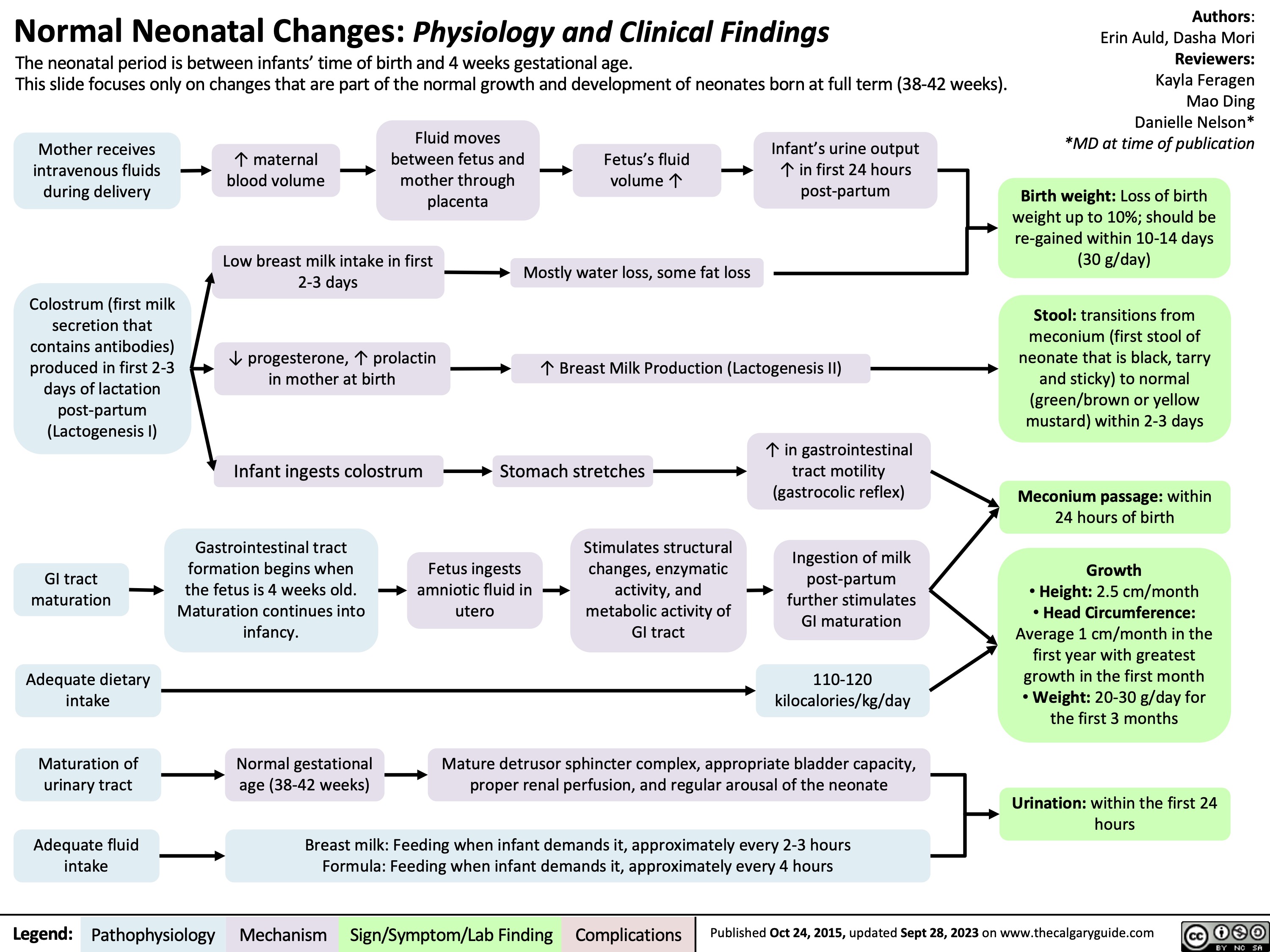

normal neonatal changes pathogenesis and clinical findings

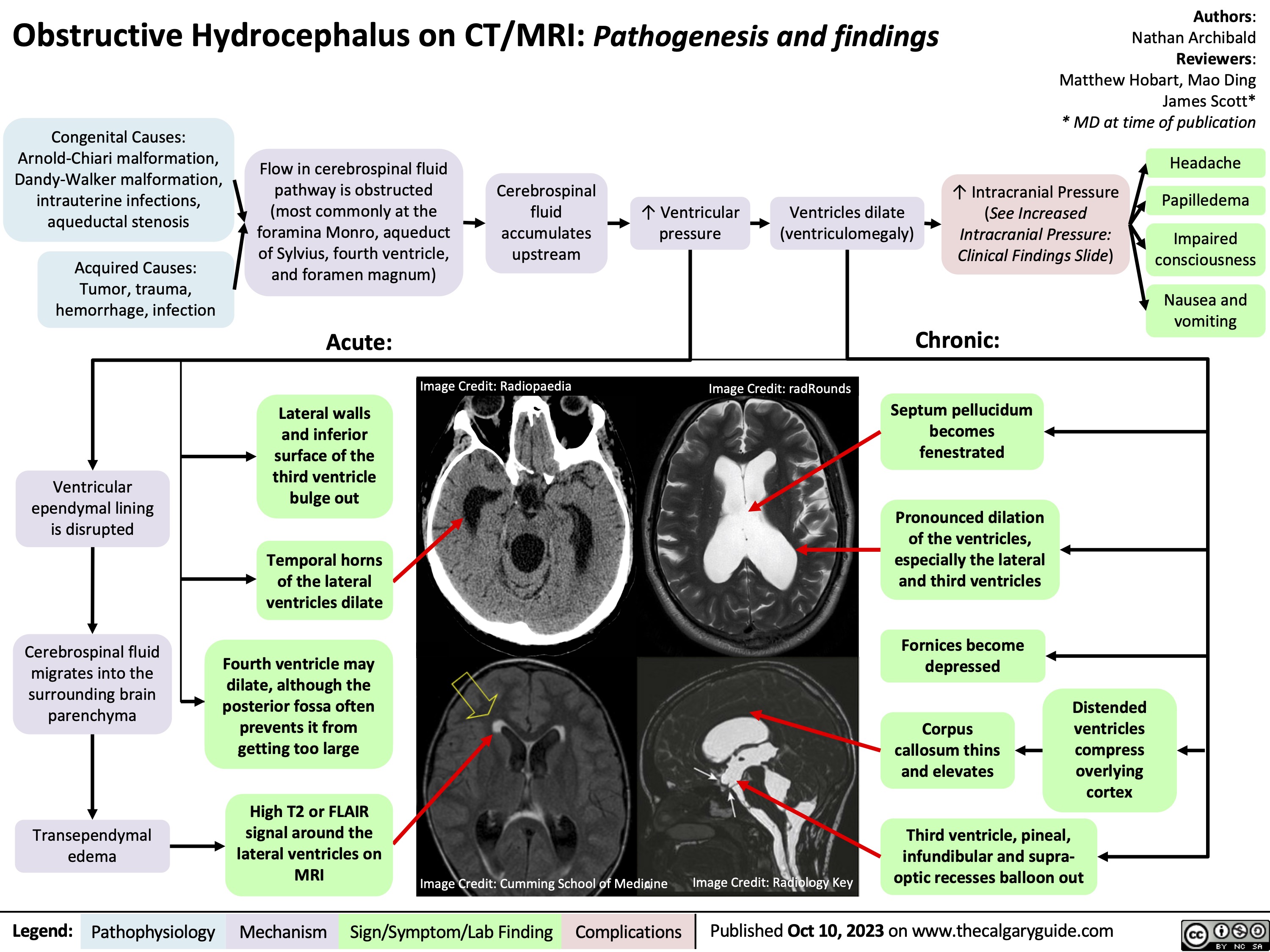

Obstructive Hydrocephalus on CT MRI Pathogenesis and findings

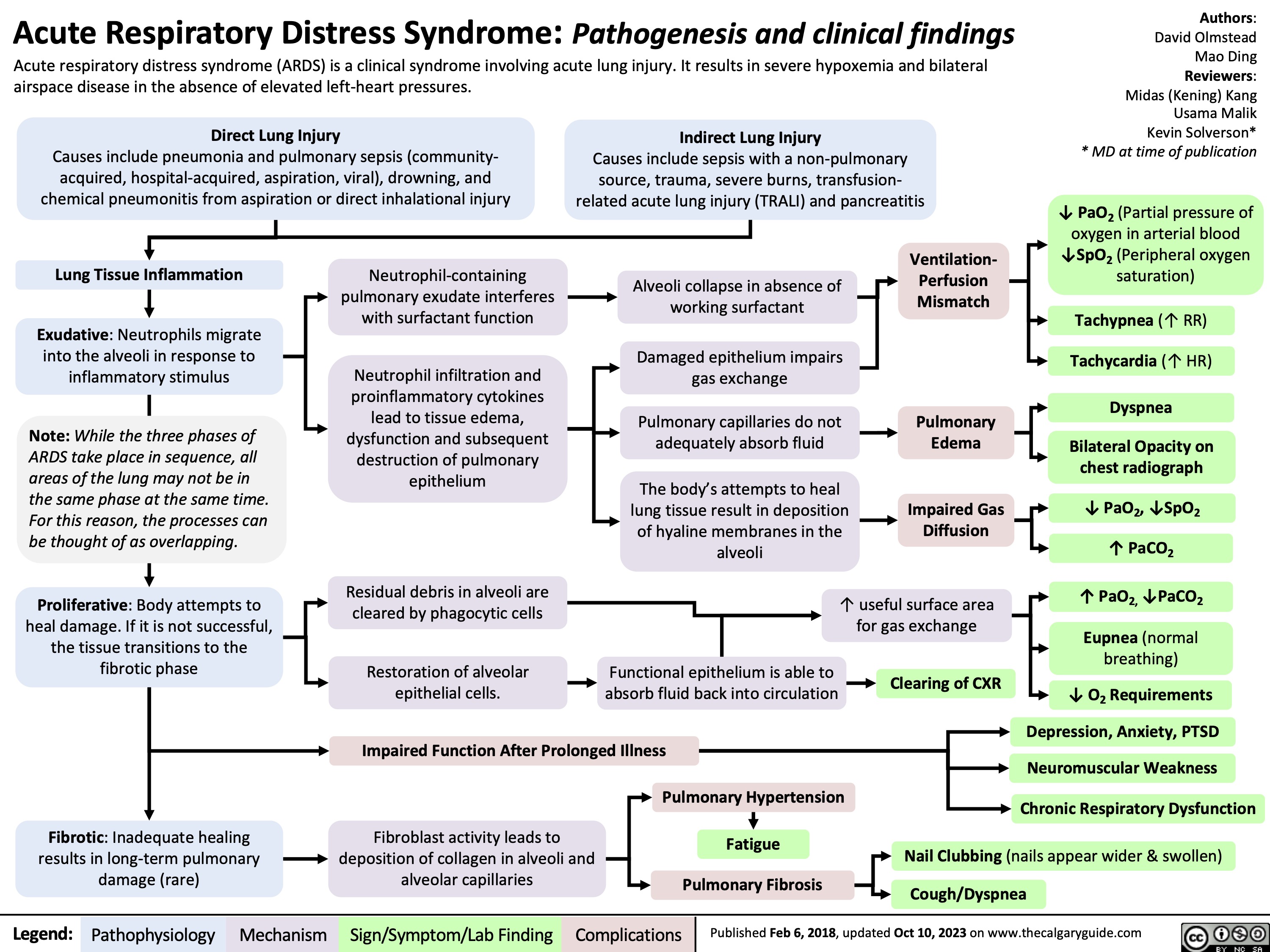

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

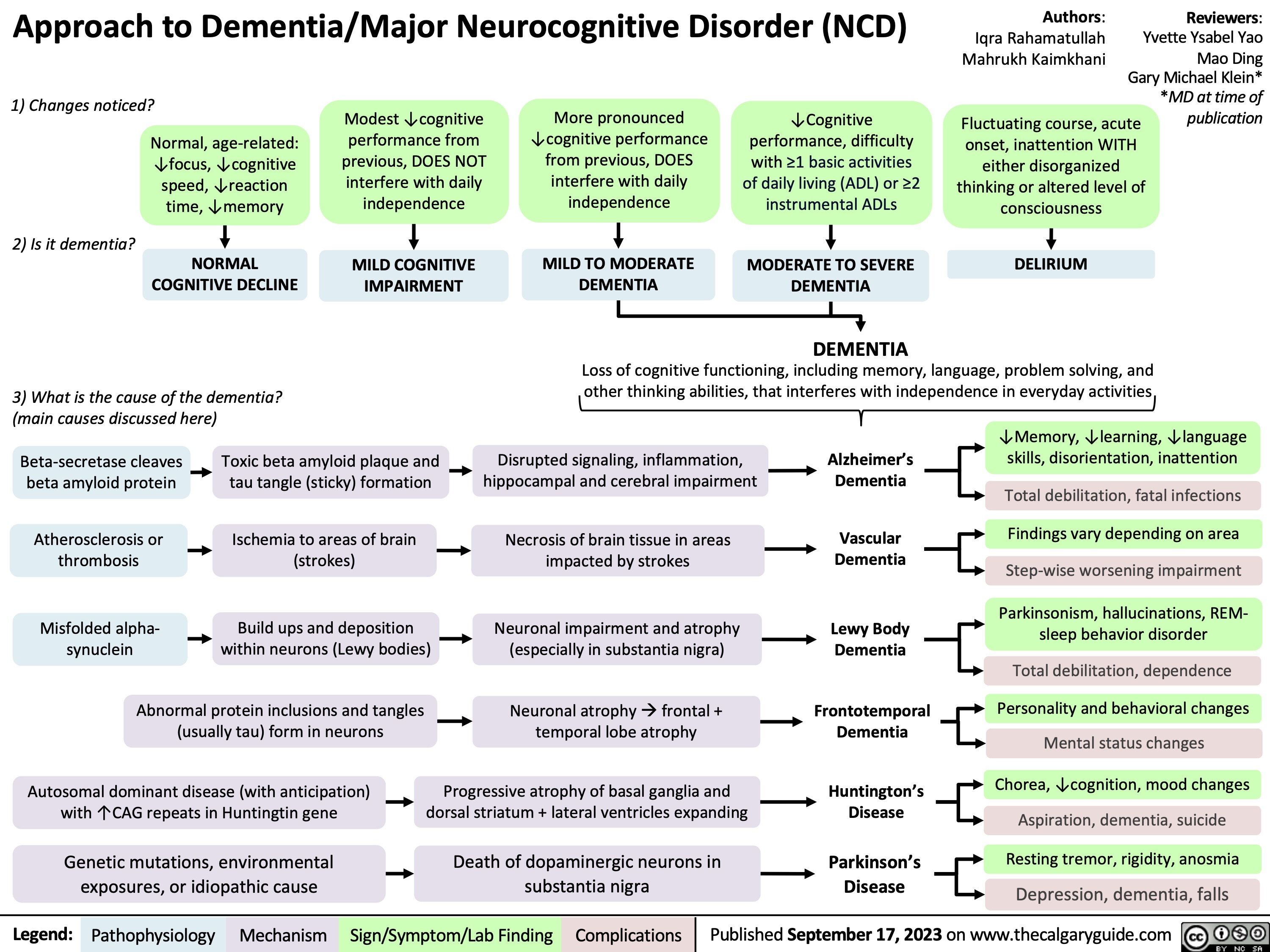

Approach To Dementia

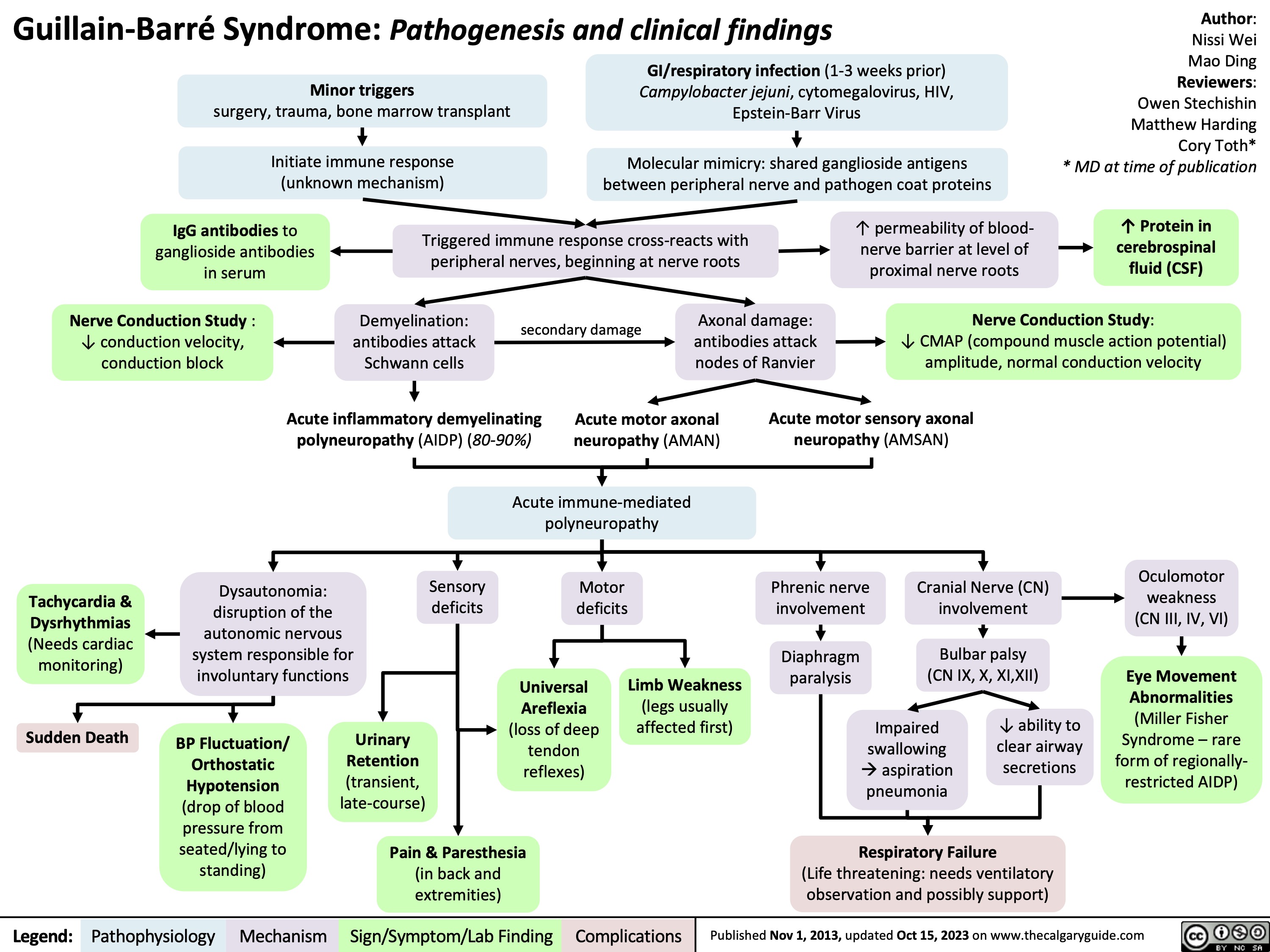

Guillain-Barre Syndrome

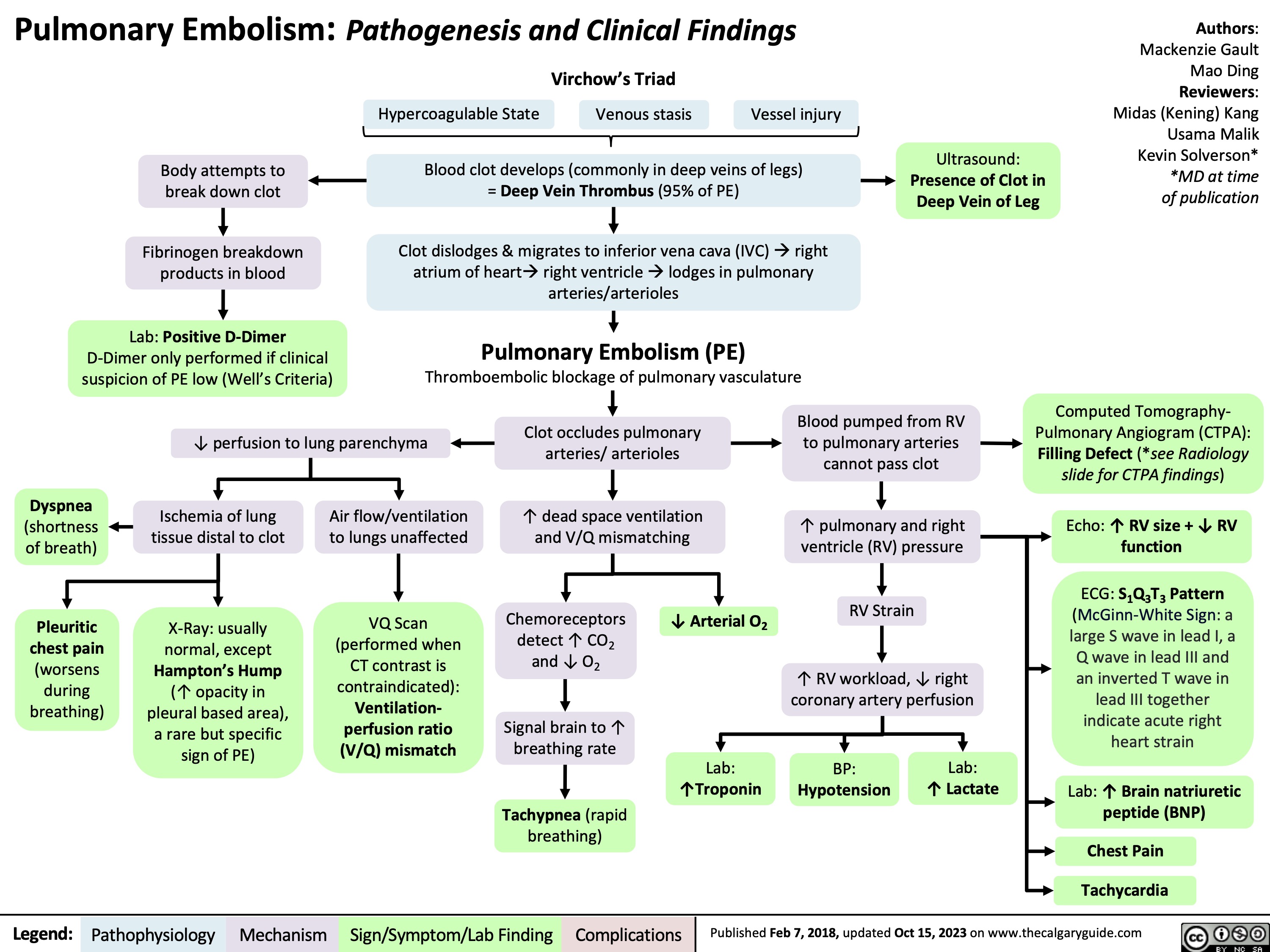

Pulmonary Embolism Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

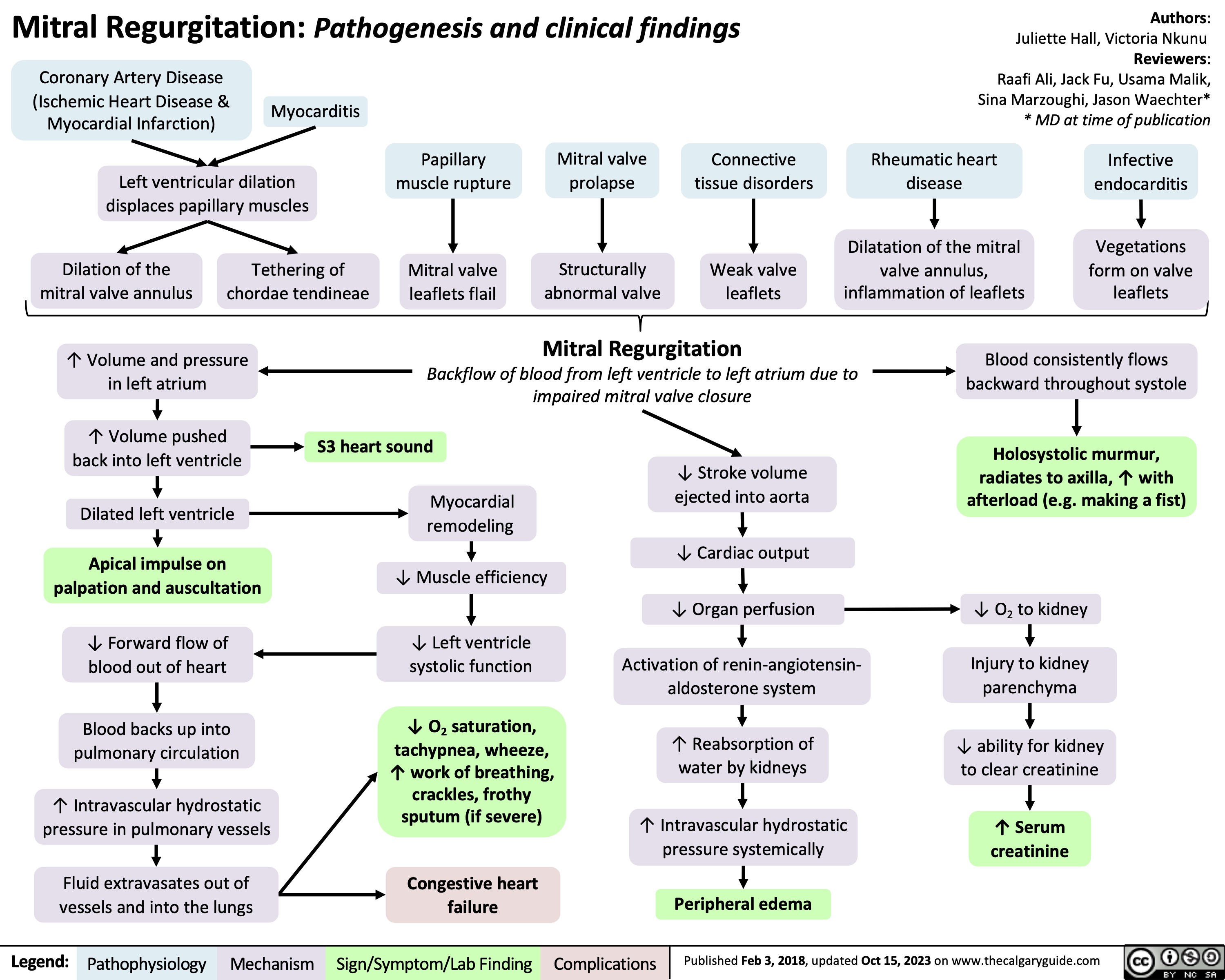

Mitral Regurgitation Pathogenesis and clinical findings

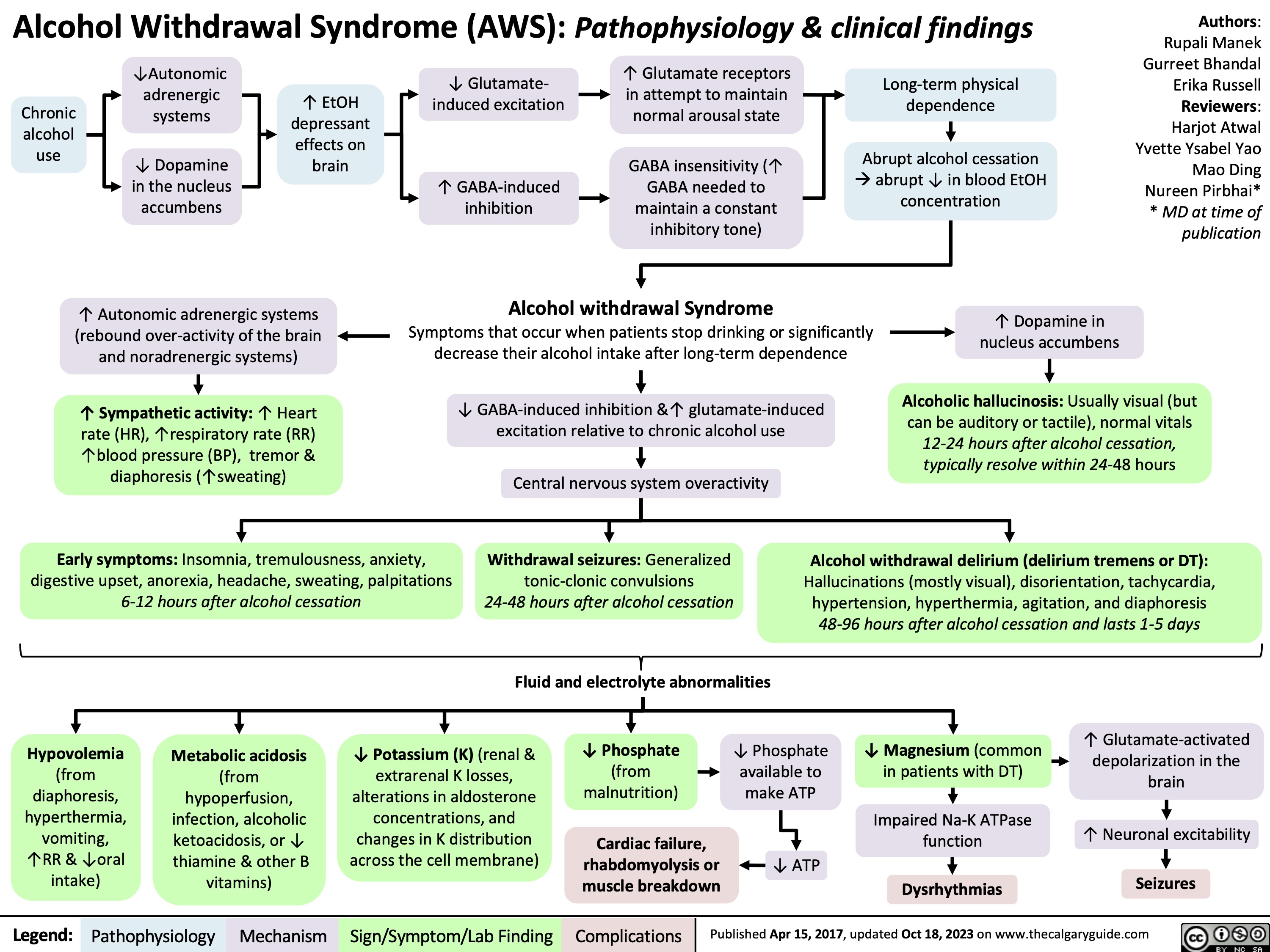

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

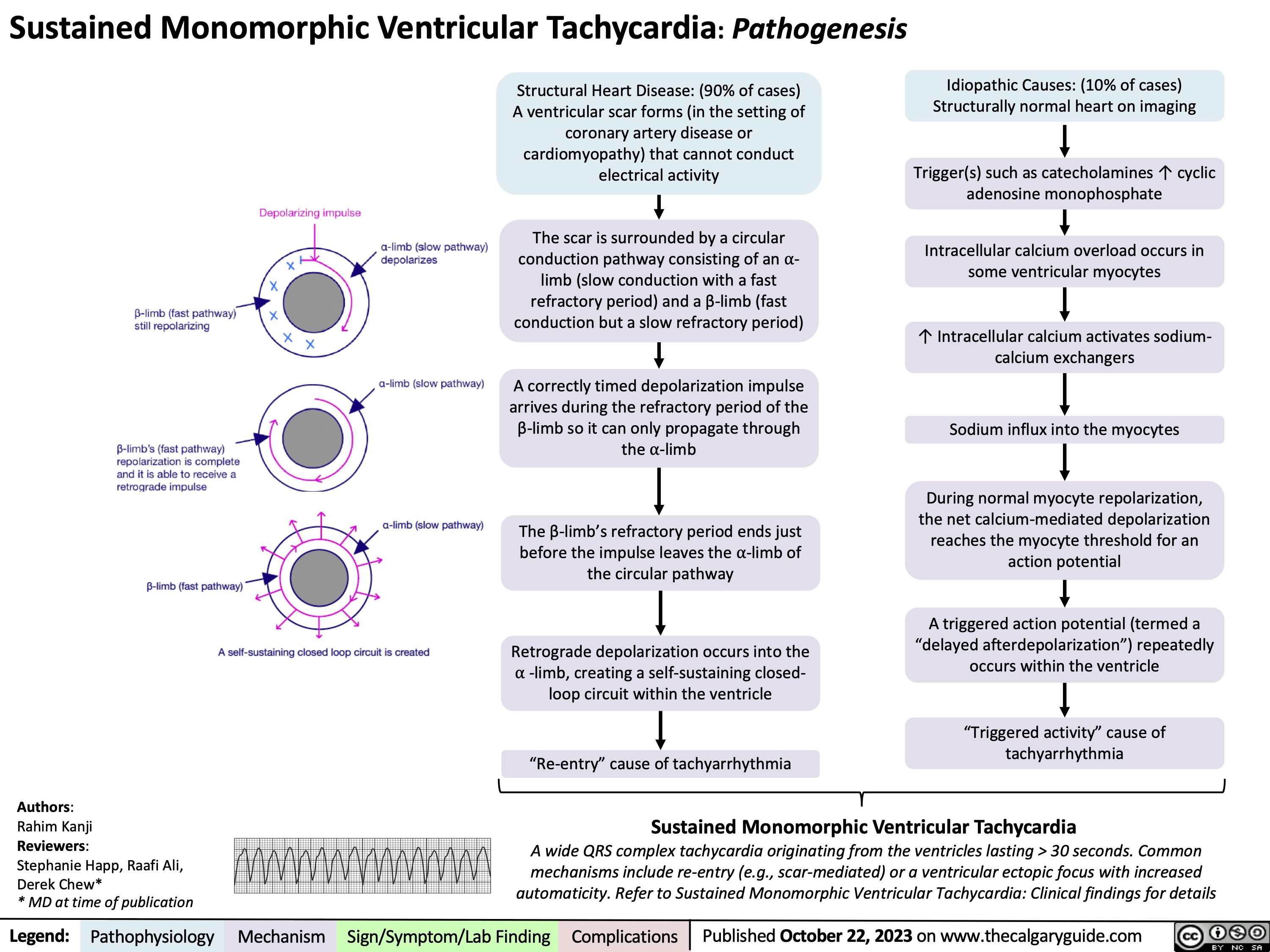

Sustained Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Pathogenesis

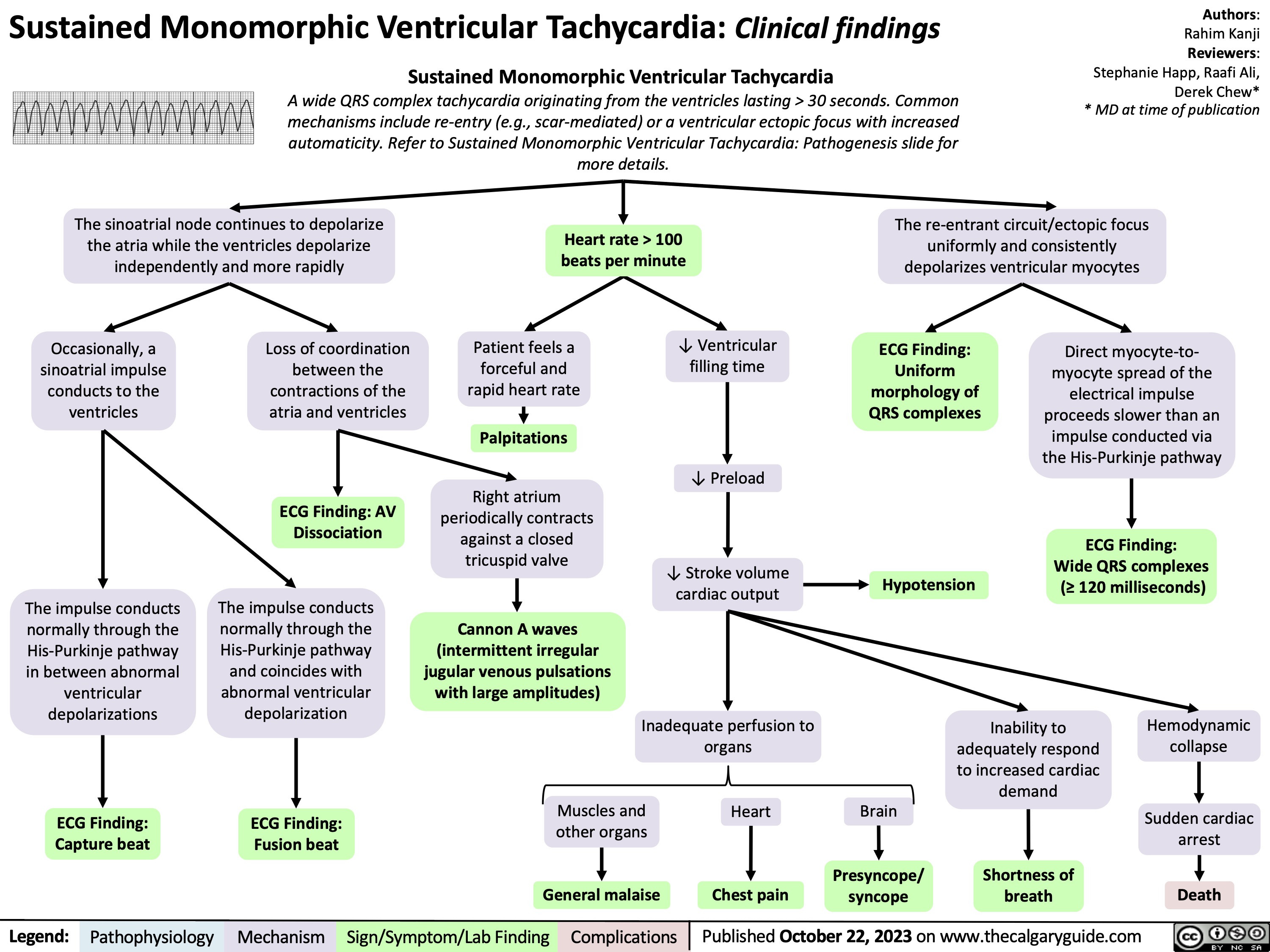

Sustained Monomorphic Ventricular Tachycardia Clinical findings

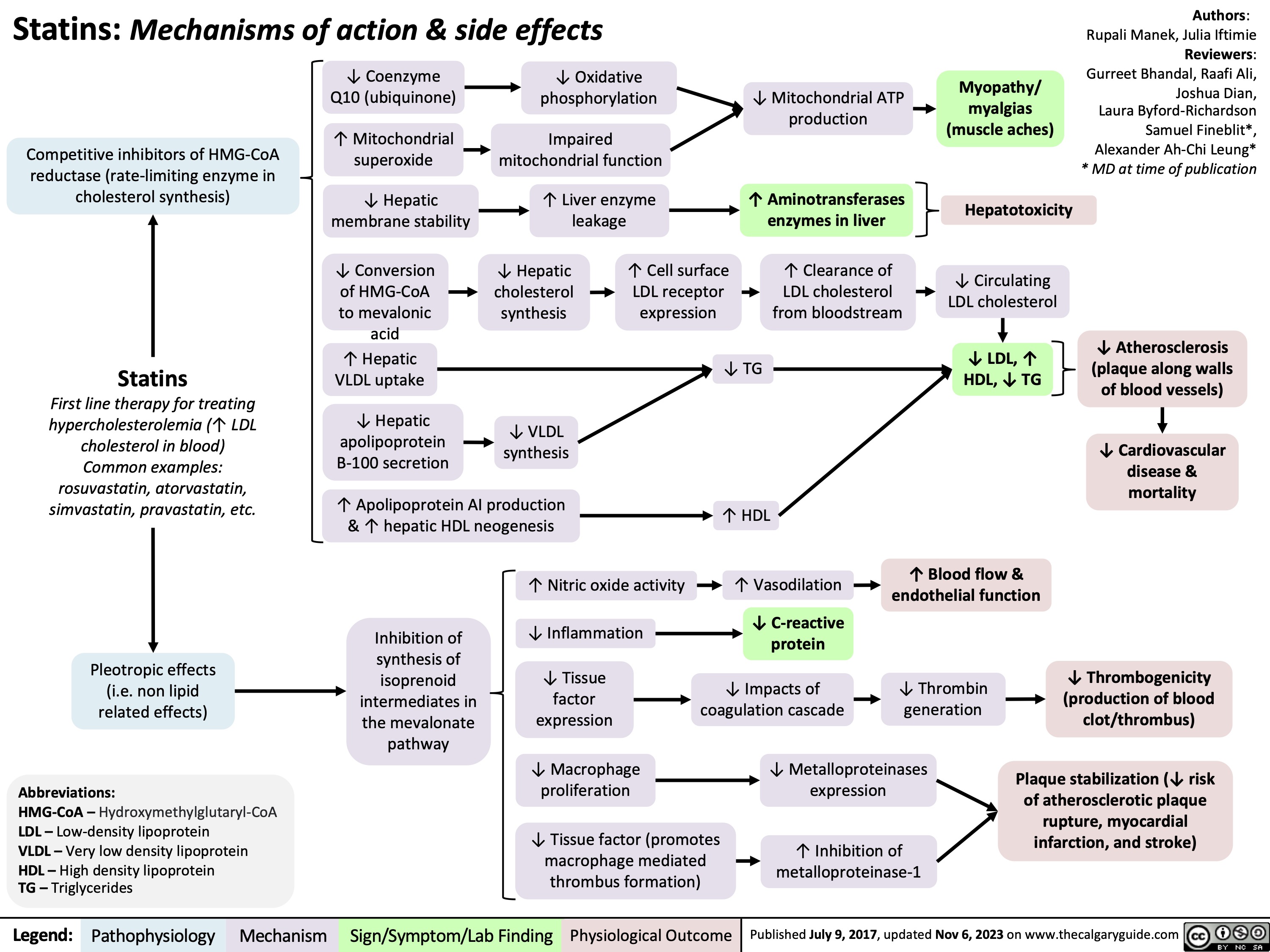

Statins Mechanisms and Side Effects

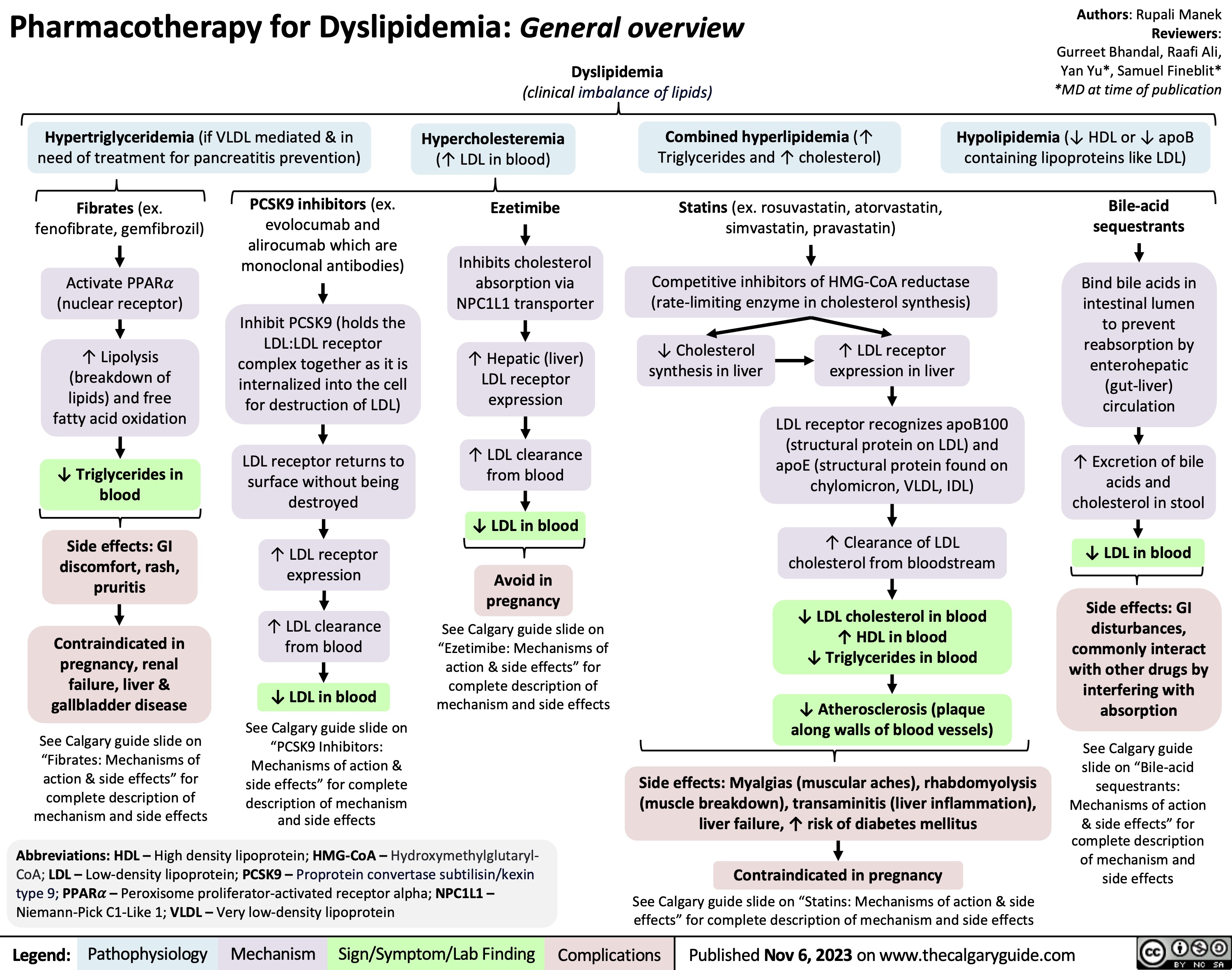

Pharmacotherapy for Dyslipidemia Overview

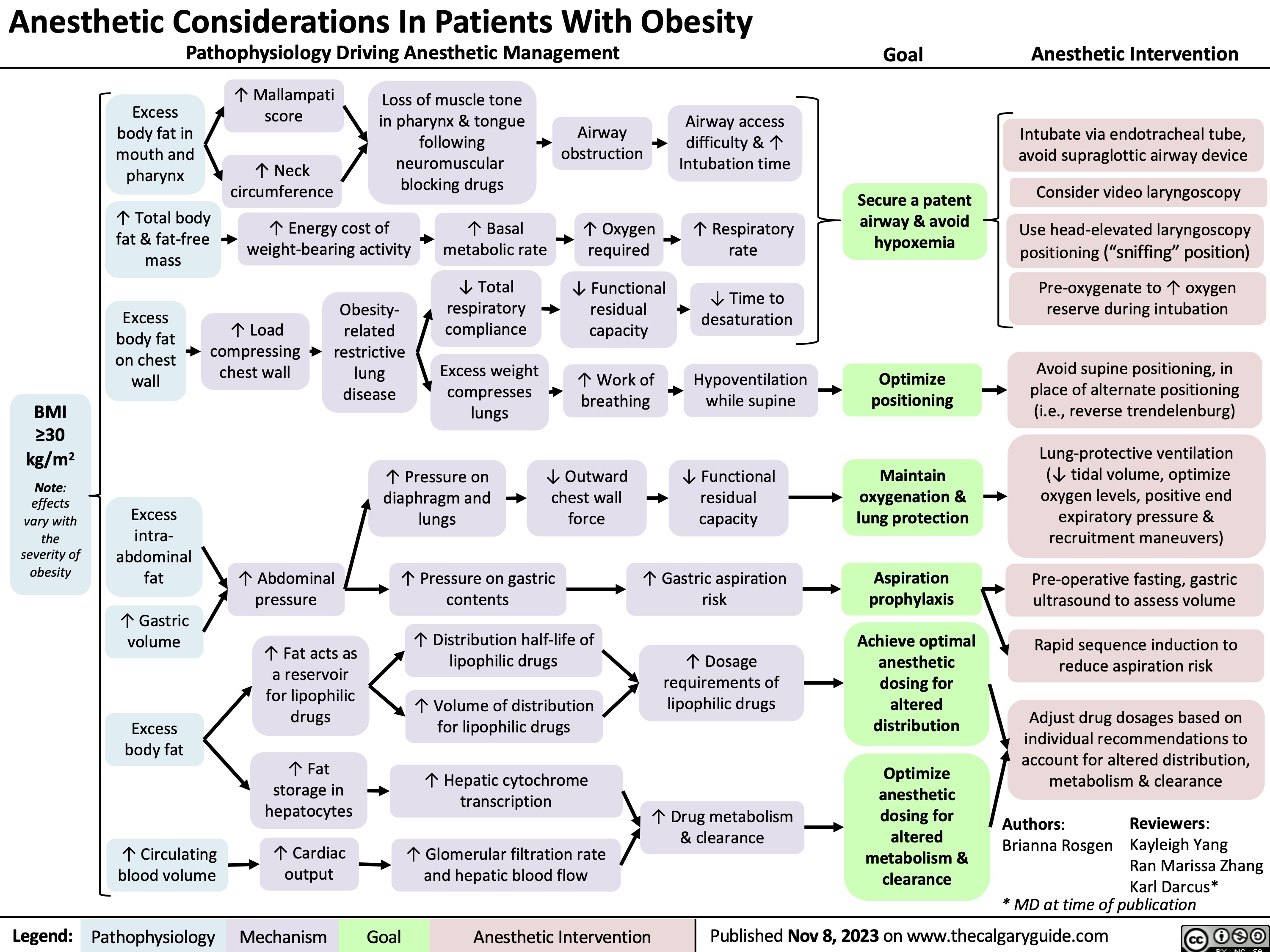

Anesthetic Considerations for Obese Patients

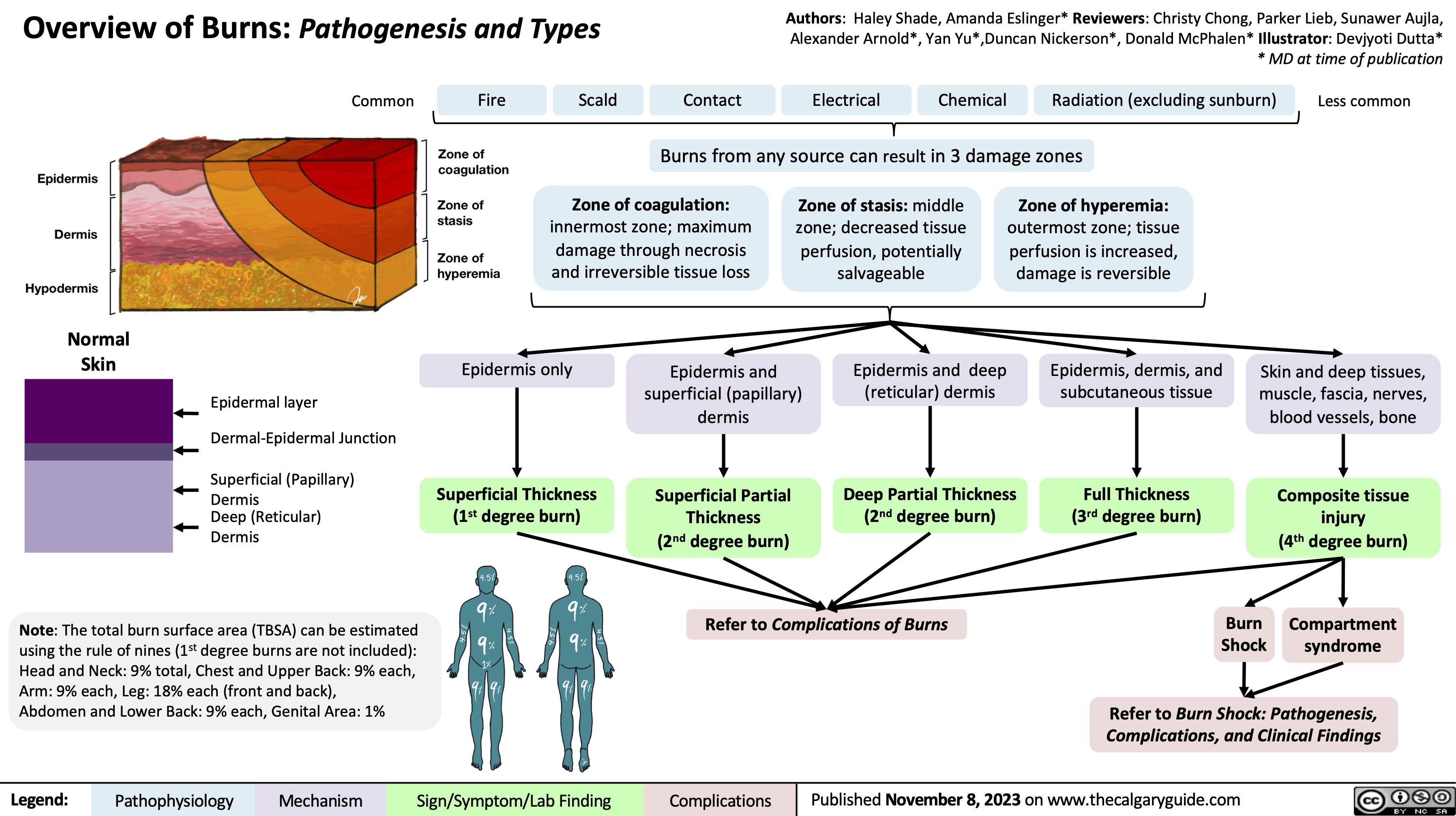

Overview of burns

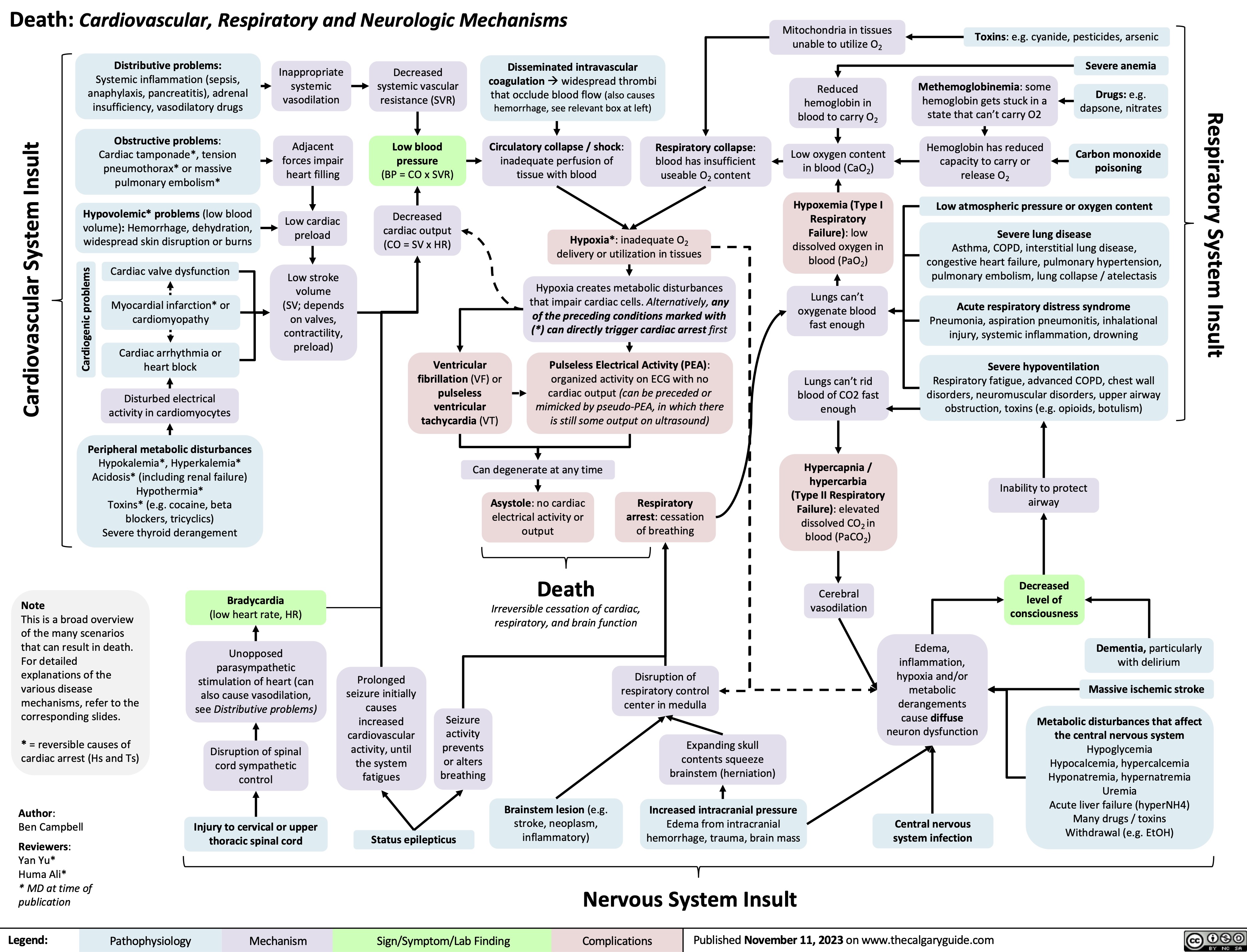

Death Cardiovascular Respiratory and Neurologic Mechanisms

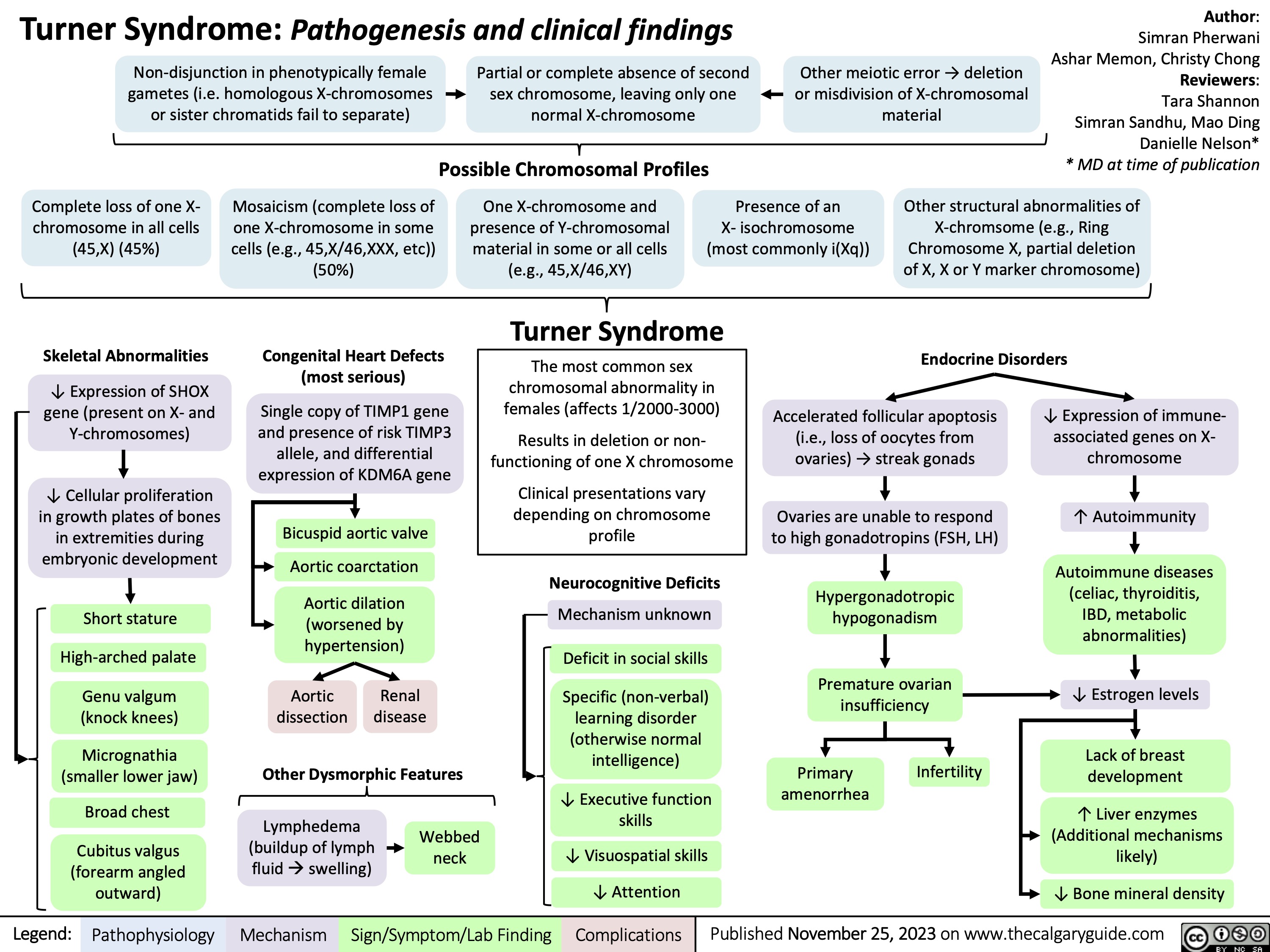

Turner Syndrome Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

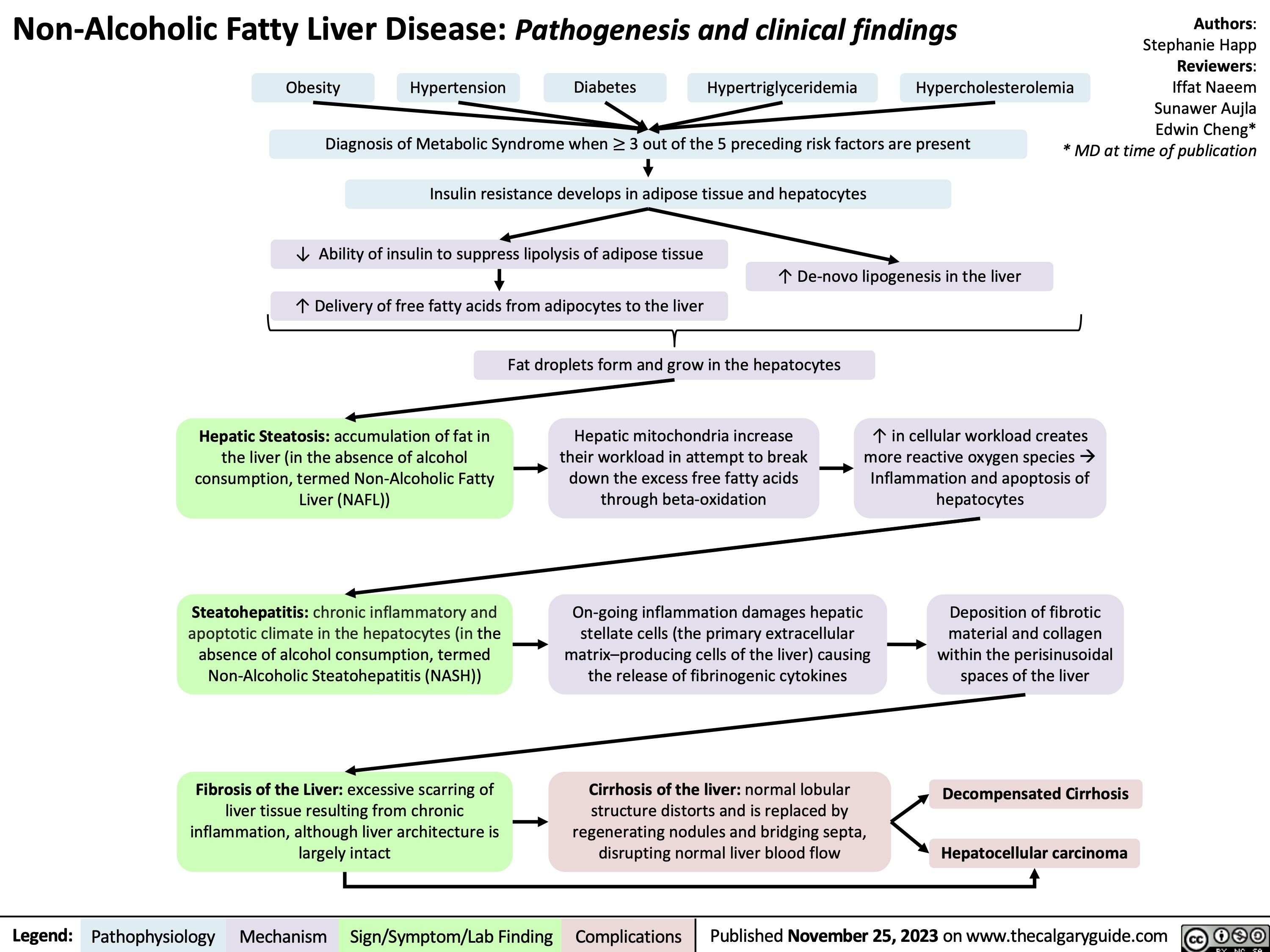

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

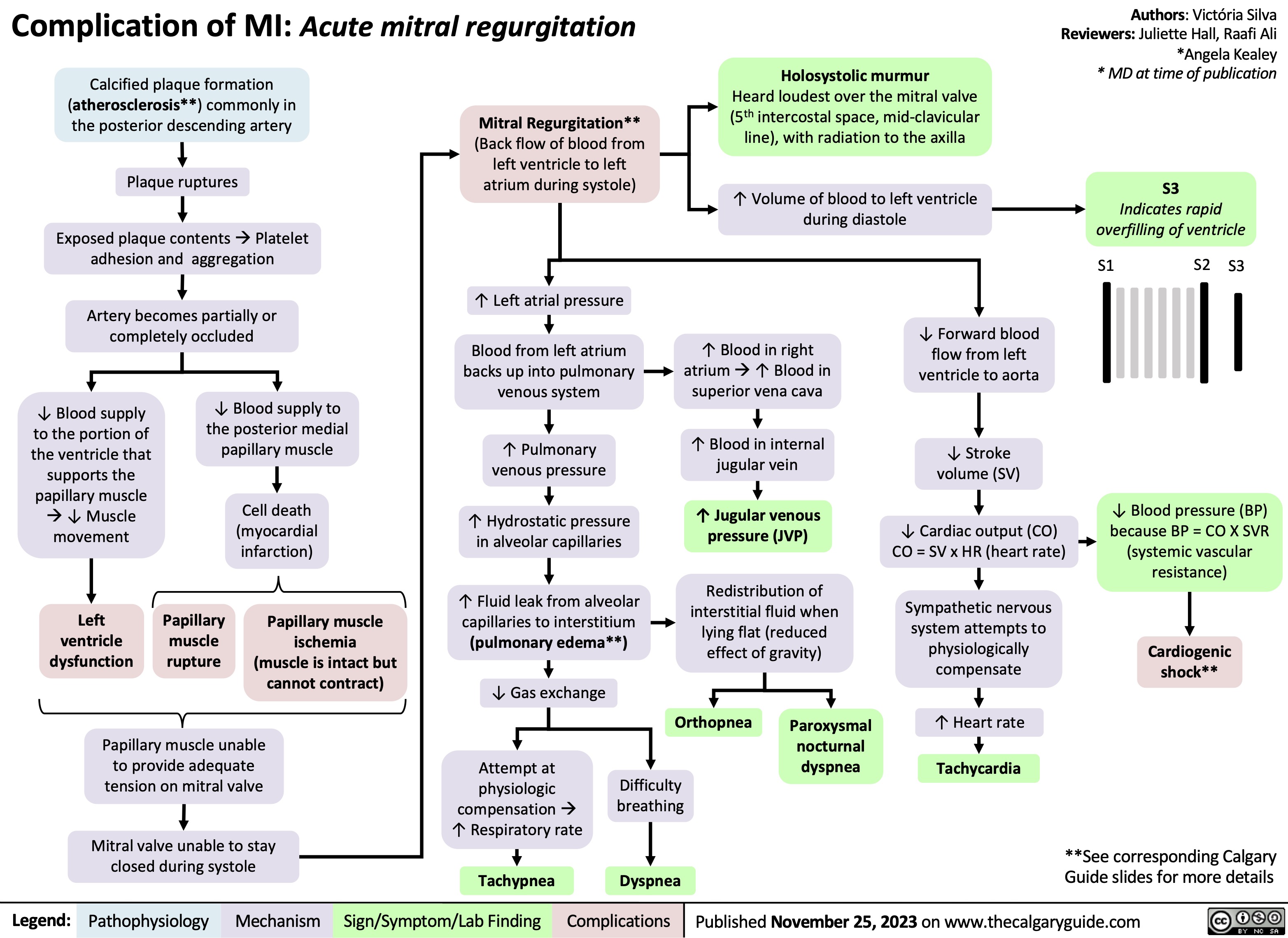

Complication of MI - Acute Mitral Regurgitation

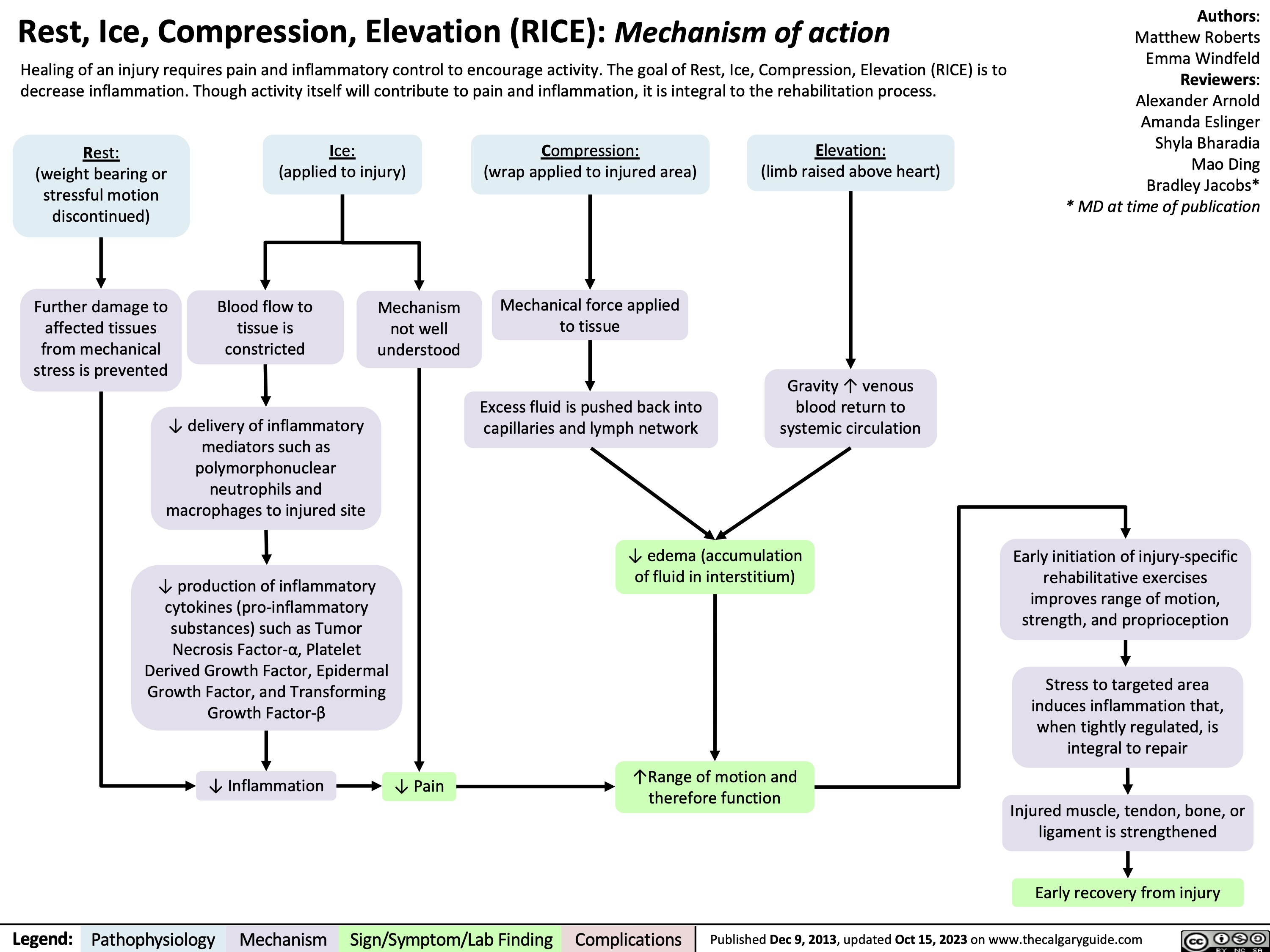

RICE mechanism of action

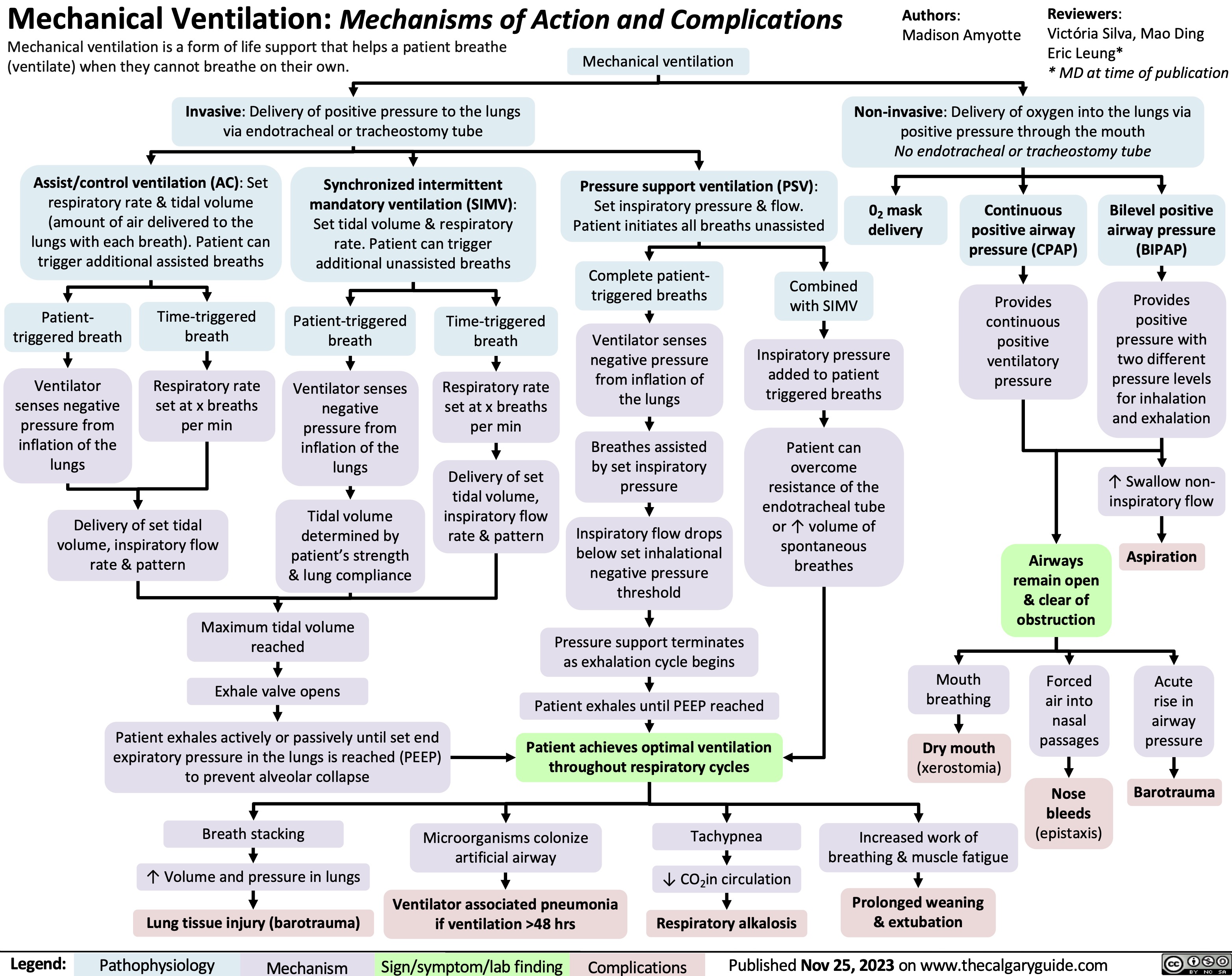

Mechanical Ventilation mechanisms of action and complications

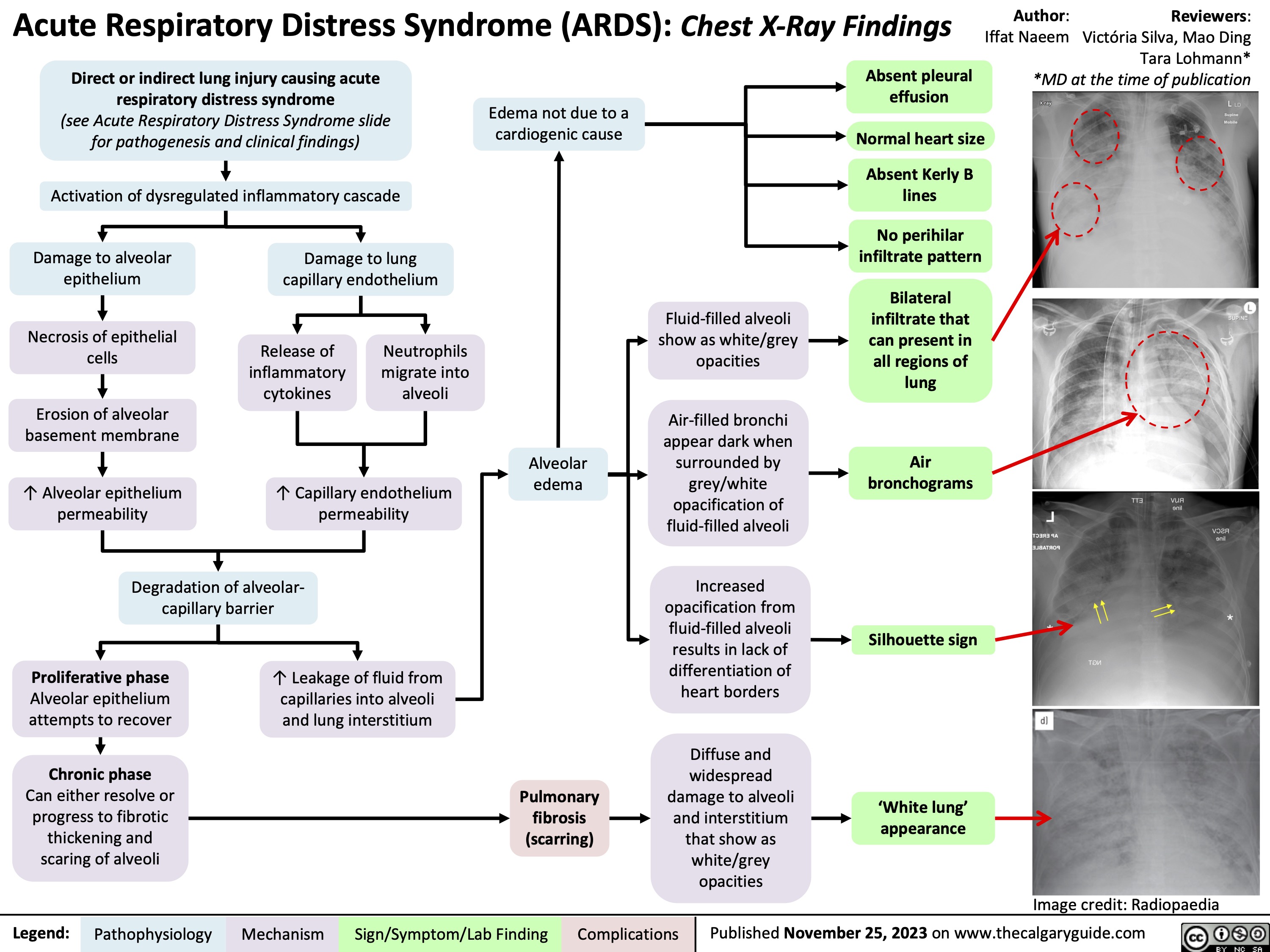

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome ARDS CXR findings

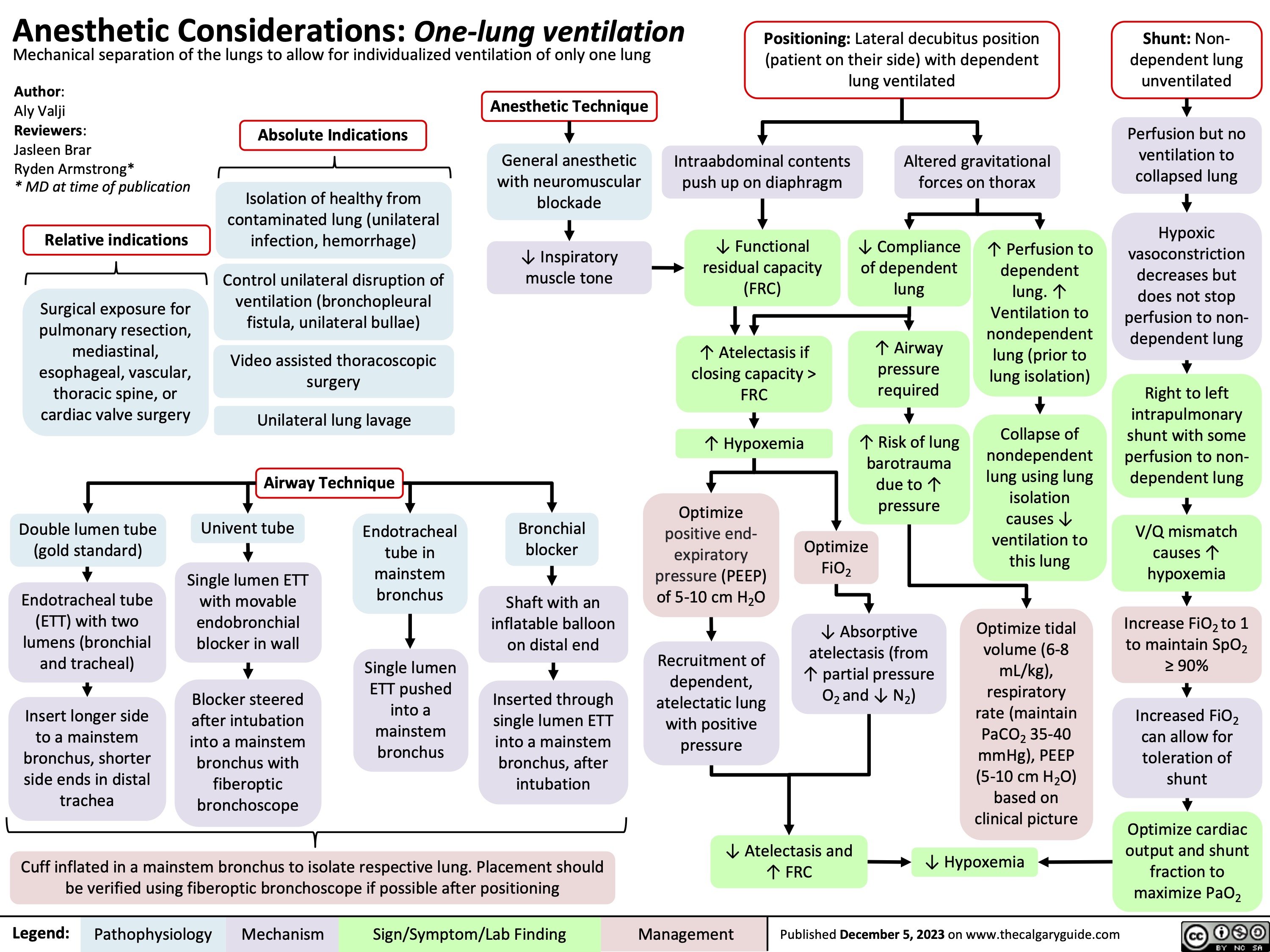

Anesthetic Considerations One Lung Ventilation

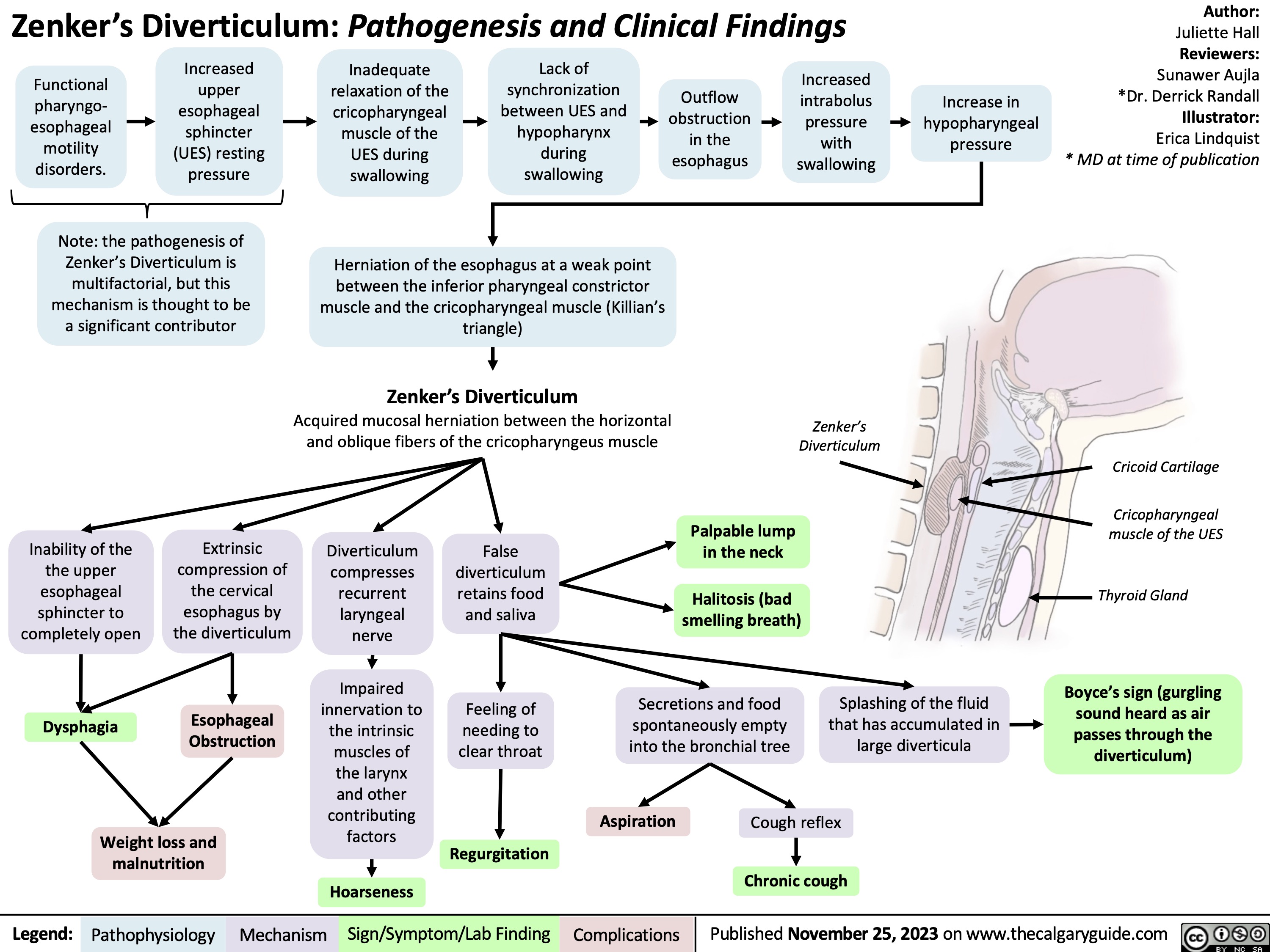

Zenkers Diverticulum Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

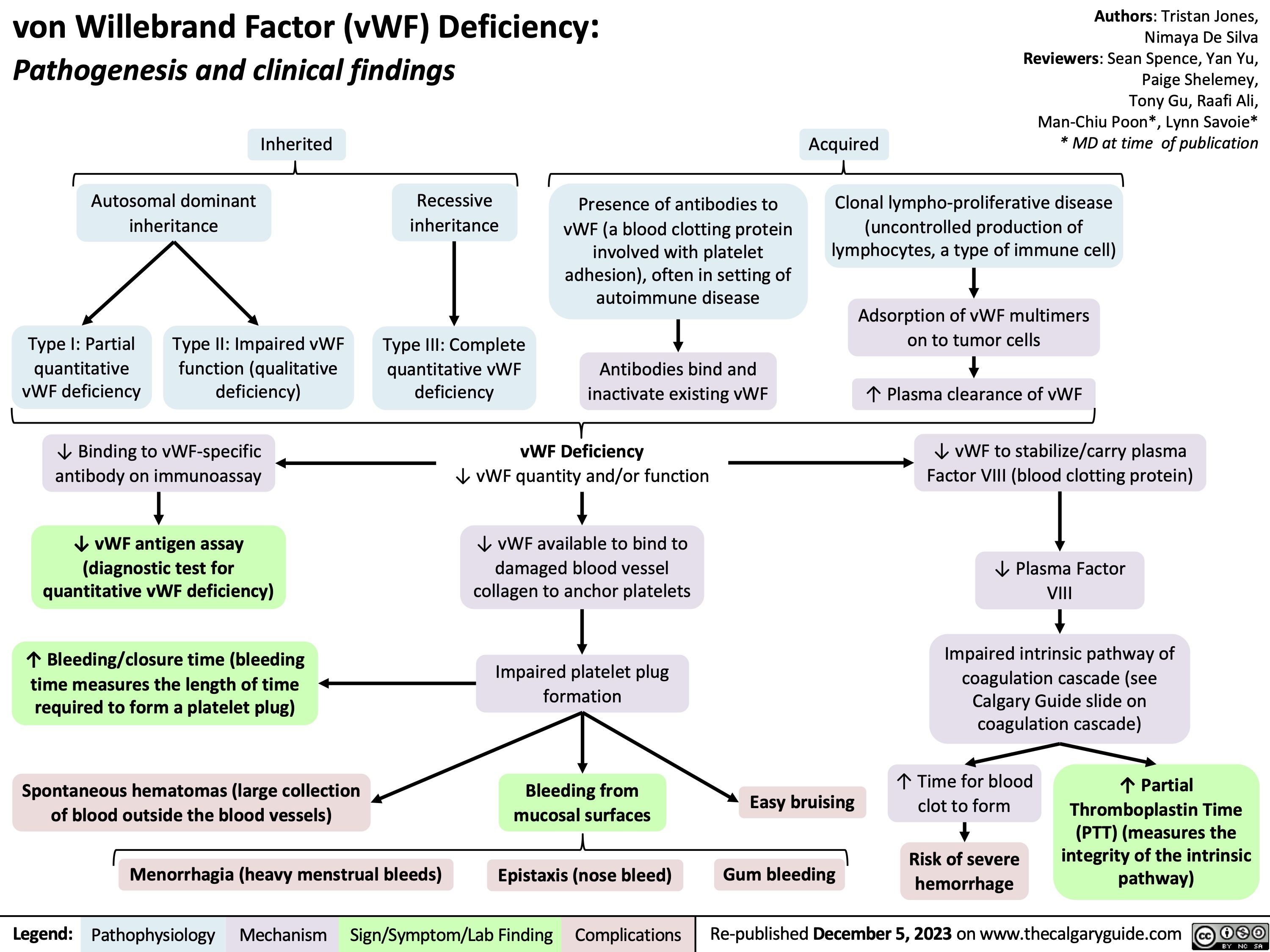

vWF Deficiency

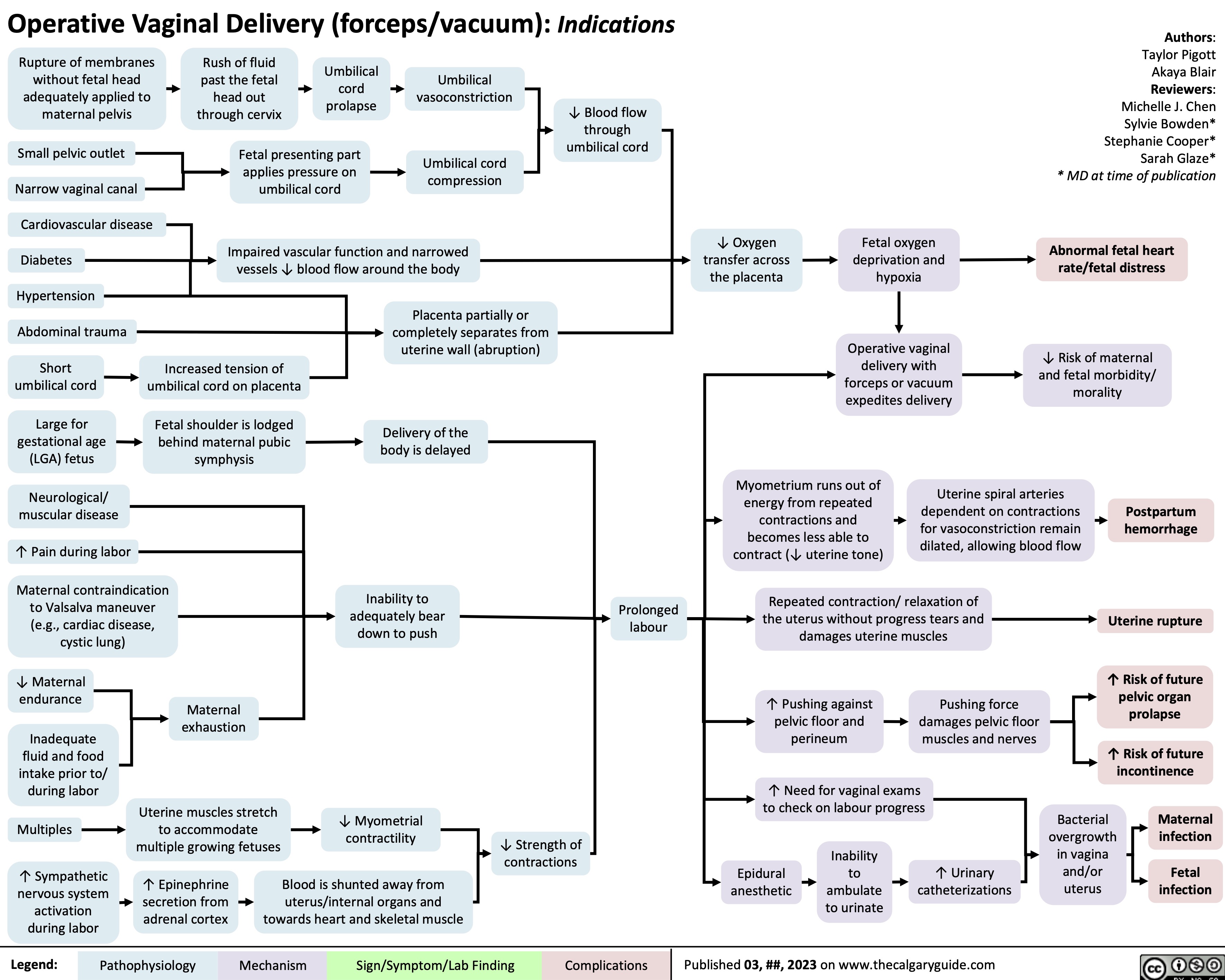

Operative Vaginal Delivery Indications

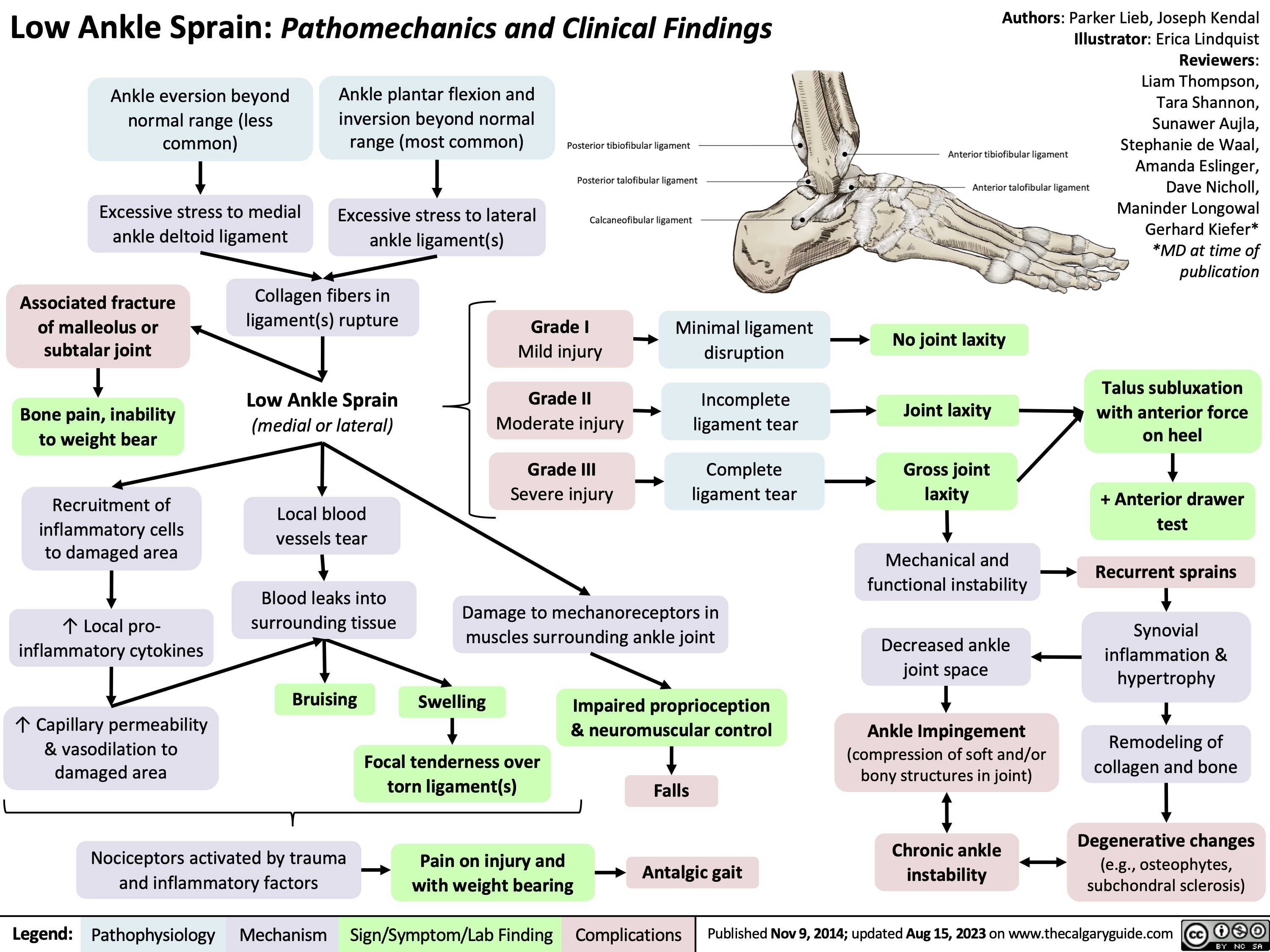

Low Ankle Sprain